Sam Bardaouil And Till Fellrath

Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath are the co-founders of Art Reoriented, a multi-disciplinary curatorial platform operating from Munich and New York, which was established in 2009. Recognised for their innovative approach to curating, the duo have worked on projects with MoMA in New York, Mathaf in Doha, INHA in Paris, IVAM in Valencia, Casa Arabe in Madrid, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, the Gwangju Museum in South Korea, the DePaul Art Museum in Chicago, Tashkeel in Dubai, BOZAR in Brussels, and the Today Art Museum in Beijing, with curatorial projects including Tea with Nefertiti,

Mona Hatoum’s exhibition, Turbulence, and the Akraam Zaatari exhibition for the Lebanese Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale.

A truly 21st-century initiative, Art Reoriented’s approach is to include diverse academic disciplines and cultural backgrounds into their creative process, resulting in exhibitions such as the duo’s first Korean exhibition they curated at the Gwangju Museum of Art in 2014: Songs of Loss and Songs of Love, which was a survey of contemporary Middle Eastern art presented with a fictional narrative: a chance meeting between Oum Kalthoum, the Arab world's greatest female singer, and the similarly renowned Korean vocalist Lee Nan-Young in Paris. In their work, from writing to curating, Bardaouil and Fellrath consider 'the mechanisms of visual and literary display by which both the artist and the artwork are presented and evaluated.' As such, an ongoing critique of museological practices and institutionalised exhibition structures is central to their practice: especially when it comes to how such structures produce and reaffirm reductionist narratives and politicised modes of presentation. This has led to what has become a trademark of Art Reoriented’s curatorial practice: which aims to excavate 'art-historical narratives that can be positioned as a framework for the reconsideration of the contemporary moment of artistic production.'

In this interview, Bardaouil and Fellrath discuss their experience of having visited four Asian biennial/triennial exhibitions in 12 days, followed by a visit to the Liverpool Biennial, while reflecting on their practice through past projects.

You visited the following biennial/triennial exhibitions in 12 days: Seoul, Gwangju, Yokohama, Taipei, and Liverpool. How did each differ and to your mind, which stood out the most?

They each stood out for a number of reasons. Taipei had a very dynamic and open-ended point of view vis-à-vis the theory of the anthropocene, while Gwangju was a tightly curated exhibition. Seoul Media City felt like a manifestation of a guttural 'feeling' rather than an expression of an intellectual argument, and Yokohama had the emotional quality of a comprehensive artistic installation much more than it resembled a conventional show. Maybe, unlike the others, Yokohama, benefited from the fact that its curator was Yasumasa Morimura, one of Japan’s foremost contemporary artists. Left with questions on how to proceed after decades of a stagnant society that was shaken to the core by the recent Fukushima nuclear disaster, the exhibition emotionally captures artistic relations and successfully avoids ever becoming literal. References to the country’s first nuclear tragedies in Nagasaki and Hiroshima were subtly woven into the story, much the same that many works were from earlier decades, creating a sense of timelessness not only of art, but of a society’s questions. Multi-layered and carefully presented, the show felt at once locally driven and globally relevant in a world that is faced with more questions than it shares any common visions for the future.

Michael Stevenson, Strategic-Level Spiritual Warfare (2014). Commissioned by Liverpool Biennial 2014. Photograph by Mark McNulty.

Do you feel that, from your observations, Asian biennials operate differently to their Western counterparts? In other words, do they perform a different function both for the public and for artists and institutions? I'm interested in how you have seen these formats appropriated and how they have adapted to contexts, while also bearing in mind discussions on the widespread adoption of the biennial/art fair format globally in the past two decades.

We don’t think that 'all' Asian biennials function based on the same modus operandi: that would dilute the distinct historical and cultural specificities of each of them. It is perhaps safe to say that all these biennials offer artists opportunities to make works that otherwise would have been challenging to produce independently. Beyond that, it all depends on the vision of the artistic director for that particular edition. Jessica Morgan’s emphasis on performance with works as haunting as Minouk Lim’s installation with bones in containers placed in the square at the entrance of the Gwangju Biennale brought out a very specific resonance with Korea’s war, the purging of Communists and Gwangju’s history of political uprisings. In 2013, the Singapore Biennale had 27 co-curators who were brought together in a bold move to offer their viewpoints on artistic practices in Southeast Asia. That made for a very different, much more eclectic experience. Biennials can be critical platforms for the articulation and elaboration of complex positions and attitudes towards art and its position within networks of social and cultural realities. They provide opportunities to rethink and imagine new mechanisms of exhibition-making and audience engagement. Despite ostensible differences, it seems to us that all of the biennials that we have visited, be that in Asia or in other parts of the world, are having a go at it.

Minouk Lim, Navigation ID (2014). Credit: Stefan Altenburger. Gwangju Biennale 2014.

As a curatorial platform, Art Reoriented's approach is to excavate 'art-historical narratives that can be positioned as a framework for the reconsideration of the contemporary moment of artistic production.' How would you define the contemporary moment?

You might be familiar with a great 1999 neon piece by artist Maurizio Nannucci that says: 'All Art Has Been Contemporary'. This is a statement that sums up the crux of our approach. When you look at a 13th-century miniature painting from Maqamat Al-Hariri, a Futurist painting by Di Chirico, or even Gui pitchers from the Neolithic Chinese Dawenkou culture, you should keep in mind that the artists who created these pieces thought of themselves as contemporary as much as Beuys did when he made his performance pieces, when Ofili painted his controversial Madonna, or even when Hirst split his shark. In our years of curating we are yet to come across an artist who thinks of himself or herself as outdated—although some might think so. The fact is, true artists are always at the forefront of their time, constantly expanding the possibilities of aesthetic and semantic possibilities. With this in mind, we see ourselves as contemporary curators of art, rather than strictly curators of contemporary art. These are two very different things. We are constantly looking at artists, artworks, objects, documents, and buildings, and so on, from all periods and seeking to complicate the narrative surrounding them by unpacking their contemporaneity and collapsing the boundaries of style, period, and media.

Your curatorial approach has been showcased in a number of projects, including Told / Untold / Retold: 23 stories of journeys through time and place at Mathaf Museum of Modern Art in Doha, which presented 23 contemporary artists with roots in the Arab world. The exhibition recognised the experience of artists today as being one of 'constant transmigration across a diversity of cities and locations, yet never escaping redundant geographical labels through which their work is misconstrued.' You noted how artists are 'in perpetual metamorphosis, in a state of "in-betweenness".' In this exhibition, which took place in 2010/2011, the cultural framing that can so often box artists in was subverted through a recognition of the complexity of experience. Could you talk about why you decided to approach curation in this way, and for what reasons?

Told/Untold/Retold was a very special case. It was the inaugural contemporary art exhibition for Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. The museum holds a unique collection of art from the modern Arab world. For us, the exhibition provided a unique opportunity to investigate the possibilities of any lineages, or at least a dialogue between artistic practices and/or stylistic affinities from past generation and current artists coming from the Arab world. It did not take us long to realise that despite an alarmingly widespread lack of knowledge of the history of modern art in the region by the younger generations, these artist shared a similar predicament with their predecessors; that of constantly 'transiting' between worlds. This is what we refer to as the 'Trans-modern'. This allowed them certain flexibility and opened up a world of possibilities as far as formal negotiations and aesthetic attitudes are concerned imbuing their work with a complexity of references and applications. Highlighting this specific experience was far more befitting than conceding to the more expected but dangerously essentialising narrative of: 'This is what artists from the Arab world did before, and this is what Arab artists do now.' Ultimately, the individualism of an artist should never be sacrificed for the sake for making generalised curatorial statements. This is why the exhibition ultimately settled on the notion of storytelling: Told, stories of the past that have been, Untold, stories that are yet to be told or could be, and Retold, stories that are being made and told now, in the present moment.

Eric Baudelaire, The Ugly One (2013). The Yokohama Triennale 2014.

I wonder if you can talk about the necessity for such an approach today?

Historical parallelisms are among the many approaches for proposing an interesting hypothesis. Ultimately, though, sensitive curating is about grafting each of the distinct individual contributions of an artist within a complex pattern of ideas. On one hand, the works must not be used as illustrations to a didactic curatorial argument. On the other, they should be brought together by certain logic or structure so that they are each indispensible to the telling of an engaging story. Finding that balance is what curating is all about and such an approach is beyond necessary, it is essential.

Do you see things changing when it comes to how museums present survey shows of art from a specific region or territory? And following on from this, are such framings necessary as the world becomes increasingly globalised?

Not really, unfortunately. Five years ago it was all about the veil: removing the veil, the myth behind the veil, unveil, pre-veil... Such extrapolations are replete with Neo-Orientalist undertones. Now that there are no prefixes left, institutions have steered their attention to adverbs denoting location. 'Here' and 'there', 'nowhere' and 'elsewhere', and so on. Such 'place-isms' condescendingly deny the 'other' the possibility of generating any original artistic contribution without having to borrow from the non-local! The mistake that all these exhibitions make is that they are still thinking of the 'region' from the standpoint of an anthropologist, rather than an art historian or curator, and present the artworks as documentation or evidence to a meta social, political, or historical narrative that stands out, rather than dialogues with the global reality of the world. Globalism did not start with the internet! The affluent members of the Armenian merchant community living in New Jolfa, a suburb of 17th-century Isfahan, were decorating their houses with paintings in the genre of domestic interior scenes from the Dutch Golden Age!

Of course, your work is not only about challenging rigid cultural frames in terms of regional affinities or national identities. You also consider the complexity that is expressed in the movement of objects, and the politics of how artefacts are housed and conserved. This is something you approached with another show at Mathaf, held in 2012: Tea with Nefertiti, which marked the 100th anniversary of the arrival of Nefertiti to Berlin, and which basically used the contested histories of Egyptian collections in numerous museums in the Western world as a framing device to explore the conflicting narratives that are embedded in artworks and cultural artefacts. Again, the show somehow finds a middle ground, by at once allowing post-colonial narratives to seep in to what is ultimately a relational exercise. Is this what you intended?

That, and more. For starters, the exhibition was conceived from the get-go as a touring show that began at Mathaf and then travelled to three very different institutions. The aim was to engage with collections and contexts of a very different nature and see how the exhibition would change accordingly. The exhibition at Mathaf had a very different emphasis from when it was presented at the IMA in Paris, an institution whose mandate is to promote 'Arab' art in a former bastion of colonialism. The contradiction between when the exhibition proposed and what that institution mandate stood for made for a very interesting tension. The exhibition then differed significantly when presented at the IVAM in Valencia, a museum that holds a significant modern and contemporary art collection. This was followed by the Egyptian museum in Munich where, in the newly opened contemporary buildings the exhibition comprised of interventions with the historic pieces as well as inaugurated their temporary exhibition spaces.

The exhibition aimed to question the many ways by which artworks change their meaning and agency as they travel in time and space. For example, a pharaonic bust within the context of the British Museum becomes an emblem of great imperial power, whereas, once erected in a public square in Cairo, transforms into a symbol of national pride. The exhibition, on the one hand, examines how artworks are coerced into becoming tools of propaganda by which a multiplicity of narratives can be promulgated. Moreover, it is equally interested in deconstructing the mechanisms of visual and literary display employed by the exhibition structures within intuitions such as museums through which hierarchies of style, periods, and genres become signifiers of cultural otherness.

It's interesting to think about Tea with Nefertiti not only in terms of how we allow histories to enter into the space of a contemporary art exhibition, but also how we consider the circulation of art works in an increasingly global art world. How might you compare the archeological drive and lust for antiquities amongst Western nations in the 19th century to the contemporary fervour for art in the global art world today?

They were equally driven by the desire for making money, if that is what you are saying. Henry Salt, the British Consul-General to Cairo amassed three collections of Egyptian antiquities that he sold to the British Museum and to the Louvre. His worst competitor, Bernardino Drovetti, who was appointed by Napoleon as the French Consul-General to Egypt, was infamous for the exorbitantly high prices at which he sold his collections to the highest bidder. Most of the pieces he collected are now at the Egyptian Museum in Turin. A significant number of the breathtaking Hellenistic and Roman Mummy portraits, known as the Fayyum Portraits, that adorn the Egyptian collections of museums in Germany, Austria, France, England, and even the U.S., come from the travelling sales exhibition of Theodore Graf, a Viennese Carpet merchant who lived in Egypt for some time. What we are seeing today is no different. While the terminology has changed and the packaging has evolved and might look more glamorous, the drive behind things is still the same.

Sang-il Choi, Jiyeon Kim, Grandmothers’ Lounge: From the Other Side of Voices (2014). Listening Archive. Commissioned by SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2014.

Having recently curated a show on Dansaekhwa at Alexander Gray, and having taken part in a symposium on Dansaekhwa at Kukje Gallery, I wanted to discuss the work you have been doing in and with Asia. How did you come to know of Dansaekhwa and how did you come to curating the exhibition at Alexander Gray?

Our interest in Dansaekhwa is part of our ongoing research on the experience and articulation of modernity in different parts of the world. Towards the late 1960s and early 1970s, the movement came out, on one hand, as a response to the academicism of the National Art Exhibition and a desire by its artists to distance themselves from figurative art that was being employed as a method of propaganda by the then-totalitarian government of South Korea. Ironically, Dansaekwha was immediately associated with questions of Korean cultural identity, first within the art circles in Tokyo, Korea’s former colonial occupier, and then within Korea itself. What defines Dansaekhwa, however, is primarily its deep philosophical commitment to the relationship between the artist’s consciousness and the act of making.

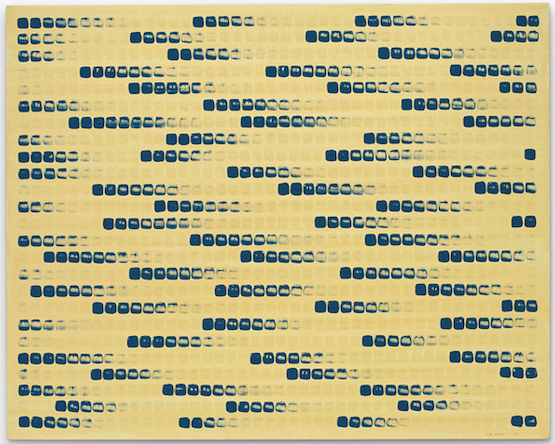

Lee Ufan, From Point (1978). Glue and stone pigment on canvas. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

So, we have been travelling to Korea for almost a decade now and have had many conversations about Mono-Ha and Dansaekhwa with the artist Lee-Ufan, whom we had known for many years and had seen his exhibition at the Kunstmuseum in Bonn in 2001. Two years earlier, there was a pioneering exhibition titled Les Peintres Du Silence at the Musée des Arts Asiatiques in Nice, France. While we had seen several works by some of the Dansaekhwa artists in different exhibitions and by visiting them in their studios, it was in 2012 that we visited the comprehensive exhibition that was put together by curator Yoon Jin Sup at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul. It was then that we decided to work on a presentation of this important movement in New York. At the time, we had been discussing the possibility of collaborating with Alex and David, the co-directors of Alexander Gray Associates in New York, so it all fell into place.

The first Korean exhibition you curated at the Gwangju Museum of Art, Songs of Loss and Songs of Love, was described to be, at its core, a survey of contemporary Middle Eastern art. But it was presented with a fictional narrative: a chance meeting between Oum Kulthoum, the Arab world's greatest female singer, and the similarly renowned Korean vocalist Lee Nan-Young in Paris. I wonder if you could talk about this exhibition and why you came to frame the show in such a way?

The fictional premise that we conceived for the exhibition Songs of Loss and Songs of Love is based on an imagined encounter between two singers: Oum Kalthoum (1904–1975) from Egypt and Lee Nan-Young (1916–1967). Both legendary within their geographical and cultural spheres, the two singers were in Paris at the same time in 1967. Oum Kalthoum was there to give a concert at the prestigious Olympia theatre. Lee Nan-Young was passing through on her way back to Korea from New York where her daughters, the famous Kim Sisters singers, had made their twentieth appearance on CBS's Ed Sullivan show. According to our fictional tale, Lee Nan-Young would attend Oum Kalthoum's concert and fall in love with her music. She would see her backstage. Over the next few days, the two divas would meet several times in the cafes of Paris. They would discuss politics and compare life stories. Over the course of a few days, a bond was forged and a promise to visit and collaborate was made. But what happened next was lost... until now. Half a century later, this exhibition was proposed as a fulfillment of Oum Kalthoum's promise to visit Lee Nan-Young in Korea.

The artworks by the 18 artists in the exhibition were placed according to a series of open-ended dichotomies. They each echo, at once, the themes of loss and love in the singers' two seminal songs Al-Atal and The Tears of Mokpo. Using fiction as a form of alternative storytelling, we intended to raise some pertinent questions about the (im)possibility of cultural exchange. Based not on facts but on an almost-event and what could have happened since, the exhibition merged the realms of fiction with reality engulfing the visitors as participants within an imagined encounter. Through the poetic metaphor of Lee Nan-Young’s 1967 imagined encounter with Oum Kalthoum, the exhibition recognised that, despite how different they are, any two or more cultures can have some things in common. This was our way of steering the locus of the exhibition and the respective gaze of the viewer, away from the otherwise implicit geographical scope of the exhibition. This was our way of shifting the focus away from the simplistic association that that would have popped up had the show been framed as a survey of Middle Eastern artists. Moreover, given the political nuances of Lee Nan-Young’s career within the context of the Korean War and the American presence, this was our subtle way of connecting with Gwangju’s political history without being overtly simplistic about it.