Senzeni Marasela: ‘My work is rooted in Johannesburg’

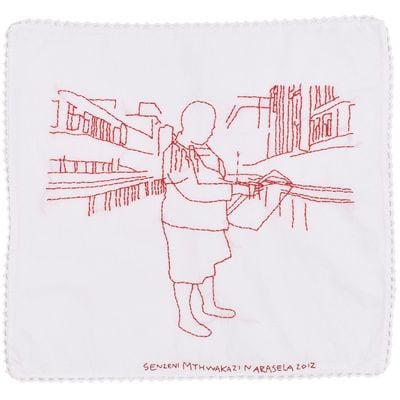

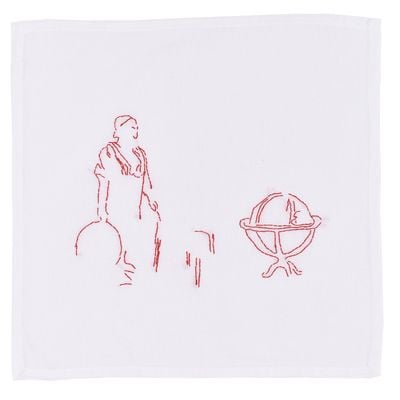

Senzeni Marasela, Ibali Lim, Searching for Gebane (2013). Courtesy the artist.

Senzeni Marasela, Ibali Lim, Searching for Gebane (2013). Courtesy the artist.

Senzeni Marasela lives and works in Johannesburg, where she explores the psychogeography of Black women's lived experiences, incorporating matrilineal stories narrated to her as a child, and wider sociocultural and political histories of South Africa.

Marasela, according to artist and academic Sharlene Khan, is part of a generation of post-apartheid female South African artists, including Berni Searle, Mary Sibande, Nandipha Mntambo, Zanele Muholi, Tracey Rose, Donna Kukama, and many others, who continue to re-centre 'bodies-of-colour . . . through the strategy of performative fictive masquerading.'1

My initial introduction to Marasela's formidable practice was by chance in 2015, when I came across her walking the streets of Venice dressed head to toe in red, and wearing what looked to me like a uniform. Her face was devoid of makeup and hair covered with a printed headscarf. The redness of her outfit complimented the aged Venetian bricked buildings around her. Carrying several 'Ghana Must Go' bags, she looked like she could have been domestic staff, and it appeared she was heading somewhere or perhaps just arriving from somewhere else.

Days later, I found out that Marasela's wanderings in the streets of Venice were part of a performance titled Intsomi zakwaXhosa/fables and fairy tales of Xhosa people (2015) staged by the Johannesburg Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale (9 May–22 November 2015). Marasela was performing Theodorah, a composite fictional character based on her mother and other women, which she performed for six years, beginning in 2013 and ending in 2019.

Theodorah is searching for her husband, Gebane, and mediates on the fate of many South African women who were separated from their families during the apartheid era, as their husbands left them in villages in search of economic mobility in urban cities. The red dress she wears is fabricated from isishweshwe cloth from Lesotho and is a traditional dress, signalling her status as a married woman.

Documentation from Marasela's performance in Venice, alongside its many iterations that occurred in South Africa and internationally, are featured in the artist's current survey exhibition Waiting for Gebane at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art (Zeitz MOCAA) in Cape Town (18 December 2020–2 May 2021). The exhibition reflects on Marasela's multidisciplinary practice, showcasing her extensive output via performance, photography, video, painting, self-portraits executed in watercolour and embroidery on paper, textiles, and installations.

In the conversation that follows, Marasela discusses post-apartheid Black female identities, feminist futures, and how living with the ethos of art-as-life opened up spaces of intimacy and isolation in her quest staking a claim for Black female visibility within an urban, social, cultural, and political context that seeks to govern and limit women's movement within it.

JDHow does your work on the lived experiences of Black South African women extend to wider conversations on the place of Black African women in society, given how attitudes towards gender equality are increasingly hostile?

SMPerhaps if I explain how I started working, this will answer your question. I began working with Theodorah, my persona named after my mother, for the body of work Theodorah Comes to Johannesburg (2004), a few years after I left the University of the Witwatersrand and at a time when I was quite disillusioned by a lot of things, such as the role of Black women in academia and in the production of knowledge and thought.

I was also engaging with quite a lot of texts, and began to observe a gap where Black women weren't allowed to speak for themselves. This operates quite pervasively in literature as well. One of my favourite books, The Cry of Winnie Mandela by Njabulo S. Ndebele (2003), which I loosely based this body of work on, frames Winnie Mandela, and other Black women, through the eyes of men.

The Winnie Mandela that we receive through the book is through the system of patriarchy that at once rejected her and at times lauded her. My concern, and in using my mother to inform Theodorah, was to create a space for women to be seen, and this is why I performed this persona over many years; to unapologetically put this figure in public space, in your face.

Put very simply, my performances were essentially about putting this woman, both as myself as a Black woman and Theodorah as a rural woman who does not speak and exists on the margins of society, into every and any space.

I wasn't carrying out a social experiment, either. It was more to do with duration and endurance. One of the things I observed as a Black woman looking the way that I did over the six years of this performance was that I was put in so many different boxes, and the amount of ostracisation and alienation that I went through was really something else—not just when I performed in South Africa, but also outside of the country, with Theodorah being held up at borders because my appearance was that of an immigrant.

On a trip to New York, two Nigerian women and I were held up for four hours trying to prove our citizenship when we had visas on our passports. Additionally, how we read space as Black women also became very important to look at, particularly in big cities. That's why Theodorah makes these repeated journeys to Johannesburg, but never quite makes it into the city itself.

These journeys are made as attempts to enter the city, which is very hostile to women, who are kept in the margins. We've had quite a lot of violence against women in the community taxi ranks, for example. Every day as a Black woman, you have to consider whether the spaces you enter are safe and work out which identity you are going to perform in order to keep this safety in check on the streets.

JDGender violence is very real and pervasive across so many parts of society, in cities but also beyond...

SMA lot of my work over the last ten years really has to do with trying to understand Black female identity, particularly in the context of Johannesburg, where I live and deal with an enormous amount of gender-based violence, which is very physical and visible in our society, but also exists in layers, from sexual to systemic violence.

The next body of work centred on this Theodorah persona will unfold as entering and trying to live in the city, because so far, the work has only existed on the margins. It was easy to occupy these margins, as I live outside of the city and the performances were based on my real-life routines.

JDWalking has been incorporated into your practice as a way to retrace and re-enact your family's history and the wider economic migratory patterns of individuals who leave the rural areas for cities. Does walking operate in your practice as a form of cultural activism within public space?

SMBecause I look the way do as a Black woman, both on the continent and visiting other countries, there are different ways one is marked as you navigate the city. For instance, I've visited cities in the U.S. where I didn't see another Black woman for miles, and I could easily be located by passersby, even if I couldn't see people taking note of my movement.

As women, the clothes we wear are cultural markers of the many roles we perform, as mothers, sisters, partners, workers, family members, wives, and so on. We constantly have to reinvent ourselves in the everyday. In performing Theodorah, I wore the same red dress daily, and it frustrated people. They couldn't handle it as I moved from one space to the next.

Now at Zeitz MOCAA, all the dresses are hung up, and people can see that I was wearing several dresses made by the same maker, a Malawian called Jimmy. All my roles as a woman were embodied in this one style of dress for the entire time. At times if offered protection, because it's not the most attractive dress on the market. Other times some men would comment on how proper I looked in the dress and if only all women could dress just like me, which I thought was quite absurd!

JDThat appreciation for dressing 'proper' is interesting...

SMWell, you know, the comment wasn't entirely a compliment because it spoke to the notion of a body being acceptable in certain spaces when covered in this way. When I went to expensive suburbs for functions, it wasn't acceptable, as people thought I was hired as a cleaner, so they'd approach me to ask for a broom or to clean up.

Initially, I was taken aback, but of course, when you do something repeatedly for so long it becomes like a second skin. You also have to understand that in the context of South Africa, and likely the rest of the continent, one of the first introductions white people—especially white women—have to Black women is someone who cleans their property, which harks back to colonial times.

In these instances, I didn't bother to correct them, and I would go fetch the glass or just walk away to avoid confrontations. Those sorts of rejections weren't just by white women. I also encountered Black women doing the same at high society weddings, because women use other women as mirrors to gauge their place or relevance in terms of beauty, wealth, and status.

I wasn't speaking much when I was in the outfit, and most of the time I'd be in a corner alone drinking, so people didn't approach me knowing my story, so it was very easy to come across as a misplaced rural woman in a high-end event in the middle of Johannesburg.

JDThe dress also directly relates to your mother, right?

SMYes. Culturally speaking, my mother had us quite late in her life, in her forties. She grew up with the mentality that you plan financially for a family, get educated, save money, and then have children. My mother dressed very modestly, and when we were growing up she didn't speak much or leave the house due to the mental challenges she faced.

We are still walking on very new terrain as Black women in this country, and I hope that the next generation carries on in this tradition.

She would wear the same dress repeatedly until she got rid of it. I feel my performance also stemmed from observing the way my mother treated the clothes that she wore; the way she would stitch that one dress obsessively. When I was older, I mentioned this to a psychiatrist, who informed me how people living with schizophrenia tend to be sensitive about particular things.

When I became interested in performance art and began engaging with the spaces where Black women have no voice, especially the type of women I grew up around in the 1980s, I began to understand how the dress was used as a marker of status.

My mother's dress told people she was a married woman. My performance practice begins from a place of observation, looking at the clothes and codes that were accepted by the women of my mother's generation, possibly without questioning it. They didn't have careers outside the home.

Theodorah, my persona, is a homemaker, and she doesn't acquire another career throughout the performance. These women don't have recognition for all of the work they do, and when they did branch out, in instances that were often domestic, their labour was still unrecognised.

My work is rooted in Johannesburg firstly, and secondly in the continent. It can't exist outside of Johannesburg because so much of it is rooted in the experiences of coming into the city. Who do I come to the city as and how do I occupy a city centre that is so masculine, violent, and very cold?

JDThe gendering of public space in cities favouring the masculine, and what this says about a widespread disregard for feminism—I'm speaking here of my context in Lagos where it gets a bad rap—is something I observe more and more. Given your practice is rooted in Black feminist thought, how has your work been received in the South African context?

SMA big one to answer, but I'll illustrate with an example. A few years back, I went to do work in the northern province, where only women get appointed to rule as queens. It took about three weeks of observing in this village for me to realise how little power the queen had, and how much her role was just symbolic of feminism, but with no real power.

For example, she actively participated in certain ancestral rituals, but when it came to governance, men behind the scenes ran everything. She also couldn't pick the men she was going to have children with. That was by the royal council of, you guessed it, men. I think that's when I realised that women in African society who have been revered have assumed roles men cannot, and then it is OK for them to be put on a pedestal.

If it wasn't for the cultural rights that she has to perform as a woman, she would not have been queen. When I read texts about her as a symbol of African feminism and strength, I began to struggle with that, after my experience of living there and seeing how things were in reality. It was a complete myth of power.

To answer the second part of your question, I do wonder about feminism, even though it's a discourse I am interested in. Is it ever possible for Black feminism to exist outside Black patriarchy? Where can we exist in a space where Black feminism doesn't have to be sanctioned by white women or Black men? Colonialism and patriarchy still lingers.

JDI'm also thinking of how you apply this idea of a woman waiting alongside walking as a form of mapping. In the documentation of the performance Waiting for Gebane, drawings, photographs, sculpture, and installation represent the surveillance and policing of Black bodies in public space, given the segregation histories and legacies of South Africa.

SMThroughout Waiting for Gebane, the character of Gebane is never represented, even though Theodorah is waiting and goes in search of him. The only way Gebane is represented is as tiny drawings that are fragmentary, but never fully represented to satisfy the viewer's curiosity. I have never felt the need to make him visible.

There are so many instances of women waiting for men. The Greek story of Penelope who waits for Odysseus for 20 years as he goes to fight in a war repeats itself with someone like Winnie Mandela, waiting for Nelson's release from prison. Mandela is a compelling case, as rather than becoming this great woman, she becomes the one who waits.

There is a type of surveillance that enters into this dynamic, where the women are watched on the 'absent' men's behalf. This was something Nelson Mandela spoke about—the fact that any time something happened with Winnie, he would hear about it instantly.

The book I mentioned previously, The Cry of Winnie Mandela, which inspires the work, really looks at this idea of women waiting under the brutal surveillance of who one speaks to, where one goes, who one talks to, and so on. In the same book, the men's lives in parallel go on as normal.

I've also had experiences within my family where women have had husbands disappear, only for them to turn up later expecting to find things as they left them. Despite his absence, Gebane was also very present. The dress I wore symbolised that I was a married woman, so for the duration, even though no one ever gets to see what he looks like, he's carried at the work's centre.

JDDo you see walking as a form of activism, a form of marginality, or more serving as a metaphor of retracing memories, as you mention? I am thinking about this in relation to the persona of Theodorah herself, who enters different public and private spaces.

SMWhen I started the performance, I had initially planned to wear the dress only whilst performing in Soweto for the duration of a year. This became very difficult to do, as there was a surge in gender-based violence and one year into it, I had to reassess the risk involved as the areas I was interested in performing it would have drawn a lot of interest, as we would have come with equipment, cameras, and photographers to document the experience.

I had to let go of that idea, and at that point, I decided I was going to commit to performing over six years. So, every day, I would be seen as Theodorah entering spaces that otherwise would be difficult for me to access as this persona.

There were times when I startled people when I entered spaces. For example, I worked for my brother-in-law's company, and I had to attend meetings dressed how I was. Walking in the streets with my plastic bags, I became this completely rural woman.

I knew I'd be judged based on what I wore, but sometimes the harshness of the reactions was unexpected. The intention was to be very available and in your face, and unapologetically so. To insert this type of woman who is marginalised, unspoken, unseen, and shouldn't be occupying certain spaces. No one was interested in her life story.

The duration of six years became very deliberate to forcefully occupy space with this presence. The reactions were varied, from people trying to take pictures in nightclubs, to attending family weddings where everyone complained about how inappropriately dressed I was and no one wanted me in the photographs. They'd ask me to accessorise or wear makeup, which I refused because it was important that I looked the same every day and existed as this woman who was constantly trying to access both a mental and physical space.

I would also take images of myself with a tripod and insert them into family memories, otherwise I would not have been present in them, and my time performing as Theodorah would have erased me from being part of the family unit. The story of Theodorah is essentially about inserting myself into spaces that didn't want to include the type of person I represented.

JDHow did this change when you performed outside Johannesburg? I actually saw you performing in Venice, although at the time I wasn't sure if it was a performance.

SMIn Johannesburg, people would very rarely speak to me, but when they did, and asked me what I did for a living and I replied I was a housewife who didn't work, they'd be so puzzled that I didn't have a career. Conversely, during my time in Venice, everyone thought I was a refugee, so I kept being offered food.

The story of Theodorah is essentially about inserting myself into spaces that didn't want to include the type of person I represented.

I remember one time I came out of a shop and a group of women from a church surrounded me, telling me that they understood the situation of Africans and could help me. When I explained I was an artist, they immediately walked away, very quickly! So the dress not only alienated me in Johannesburg, but abroad, too, as I didn't particularly look like what other Black people supposedly look like.

Put very simply, my performances were essentially about putting this woman, both as myself as a Black woman and Theodorah as a rural woman who does not speak and exists on the margins of society, into every and any space. It was very important not to take the dress off to spark these kinds of conversations.

JDCan you expand on your use of fabrics as a historic document in your practice, and the intergenerational residues related to this use of different textiles, such as isishweshwe and kaffir?

SMNow that people see the dresses on display at Zeitz MOCAA, I think they can begin to make sense of what that duration was about. It was very important to also note that the isishweshwe fabric used to make the red dresses originates from colonial times, like many fabrics that ended up in Africa.

The cloth bears all the burden of colonial history, which was a project that used every means possible to create divisions in Black society, even with something as trivial as fabric. The isishweshwe fabric I have on in the performances is actually a Basotho fabric, but because this group of people crossed over borders and moved around, it has also been adopted by Xhosa culture.

There are a lot of layers to these fabrics, and a lot of the ones I use to document my work in the current exhibition are from the colonial period, especially kaffir, which is referred to locally as 'the cloth of hiding'.

According to Xhosa myths, it is believed that the first king who escaped Robin Island was able to swim across and keep warm by being draped in this cloth. The cloth was also used by men who went to war. It's a cloth of resistance.

In all the drawings I have done of Theodorah through red stitched lines on kaffir, she appears and disappears, which is a deliberate gesture, as it became difficult when I performed to fully articulate who Theodorah was, as she's a completely fictional character. My mother didn't have the exact experience of my performed persona. For example, she was married to my father for 44 years, and they came to Johannesburg together, rather than being left behind.

My entire documentation on the process of waiting is expressed through the kaffir cloth. It became a way of writing Black women into history, through a cloth that was for many years revered as one worn by men during wars and victories.

The cloth has gone through changes in the last 20 to 30 years, as it is used in weddings where men give women parts of it to symbolise the union. It's very hip and trendy to wear at weddings, particularly by younger people, so once again it has developed a new meaning. I don't wear it due to the historical burden it carries, but I do use the cloth in my work.

JDThe Mine Cleaner (2015) and Theodorah, Senzeni, and Sarah I (2010) reframe given histories through hand-stitched gestures on fabric. How has the act of stitching served as a tool for both representation and subverting history in your work?

SMThere have been a lot of questions about why Black artists do a lot of representational work. In South Africa, we suffered censorship up until about 1996, and the idea of the self and trying to construct this is still very new.

Prior to this, identity was defined and restricted by the state. I only found out about Sarah Baartman in my twenties, and even then it was because I was digging for histories of Black women at university. The only woman we knew who occupied public space was Winnie Mandela, and she was vilified. We were taught not to be like her, and to become a particular type of woman.

When I think of other women artists working in South Africa today, such as Mary Sibande working with her alter ego the domestic worker, Sophie; Zanele Muholi, who looks at gender politics and identities; and Tracey Rose, who deals with identity politics framed by apartheid, we are the first generation to have podiums to speak, and to be able to do so freely.

Women older than us weren't able to have these opportunities to speak and consider how to claim Black female subjectivities and identities. We are still walking on very new terrain as Black women in this country, and I hope that the next generation carries on in this tradition. The process of waiting is very personal for Black women, as we wait for different things.

JDThe current exhibition, Waiting for Gebane, brings together various bodies of works across different media, from fabrics to photomontage, archives to installations, exploring this notion of women's 'perpetual waiting'. Could you expand on your disruption of this idea of waiting and emancipation from the racist and patriarchal gaze on Black women's bodies?

SMThe exhibition is centred on documenting the experiences I went through exploring this idea of waiting, of women waiting on men, and so on. There are about eight outfits included in the exhibition, including shawls that I used to cover my waist and shoulders.

I would constantly get comments from men on how respectable I looked, and eventually I decided to get rid of these additional coverings, as they became too heavy to carry around and I just got so tired of having to respond to all these comments from Black men.

In Ndebele's book, which I mentioned being an inspiration, there's a woman whose husband goes to the mines in Johannesburg. The city was built through the mining industry. In my view, mining is the source of decay of Black families. To this day, we still see mine slopes, all the way to Soweto, where the ground is sinking as a result of excessive mining. When I visited these sites, there were no signs of human presence, even though so many lives were destroyed by the industry.

There are still people who live close to the mines because it's quite cheap. There are also people called Zama Zama, who still try to make a living from these abandoned mines. So you still find a lot of Black women trying to live around these spaces with men trying to make money in an area filled with environmental challenges.

As we all wait for a new world, I think a lot of people are struggling and are being forced to wait for things that they don't understand. None of us has ever gone through this type of situation before, particularly Black women, who are reliant on the city for their employment, and who suddenly have no public life.

JDWhat are you working on right at this moment, and what are you looking forward to?

SMMy journey on view at Zeitz MOCAA is a very large body of work, but it's not everything, as I've been so prolific the last six years. I've taken on a challenge to read 100 books this year, as a way of stepping out of production, because I've worked quite obsessively.

I am also trying to articulate the experience of creating happiness in the absence of so many things due to the current global pandemic. I'm on book seven at the moment, but the list is specific to writers of the continent. I am particularly interested in literature from Zimbabwe, our northern neighbours.

One of the things I would like to explore more in the future is moving across the continent, as I tend to engage with other Black women artists outside rather than within, which is why I appreciated the conference, BLACK PORTRAITURE[S] III: Reinventions: Strains of Histories and Cultures that was held at Witwatersrand in 2016, which brought a lot of women photographers together in Johannesburg; and what Michael Armitage did in 2017 in Nairobi, bringing local and international artists together informally.

It would be great for these conversations to resume again. I love travelling to cities such as New York and showing my work elsewhere, but it would never make sense to live somewhere else, as my work is so rooted in Johannesburg—of living here and thinking through these notions of waiting. In the year I am taking off production, I'm going to work on the persona of Theodorah entering into the city and inhabiting it from within. —[O]