Thomas Houseago: Nauseous Fantasies and Exhausting Realities

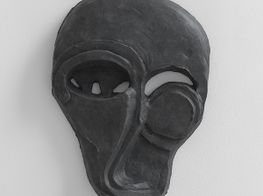

Thomas Houseago. © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Adrian Gaut.

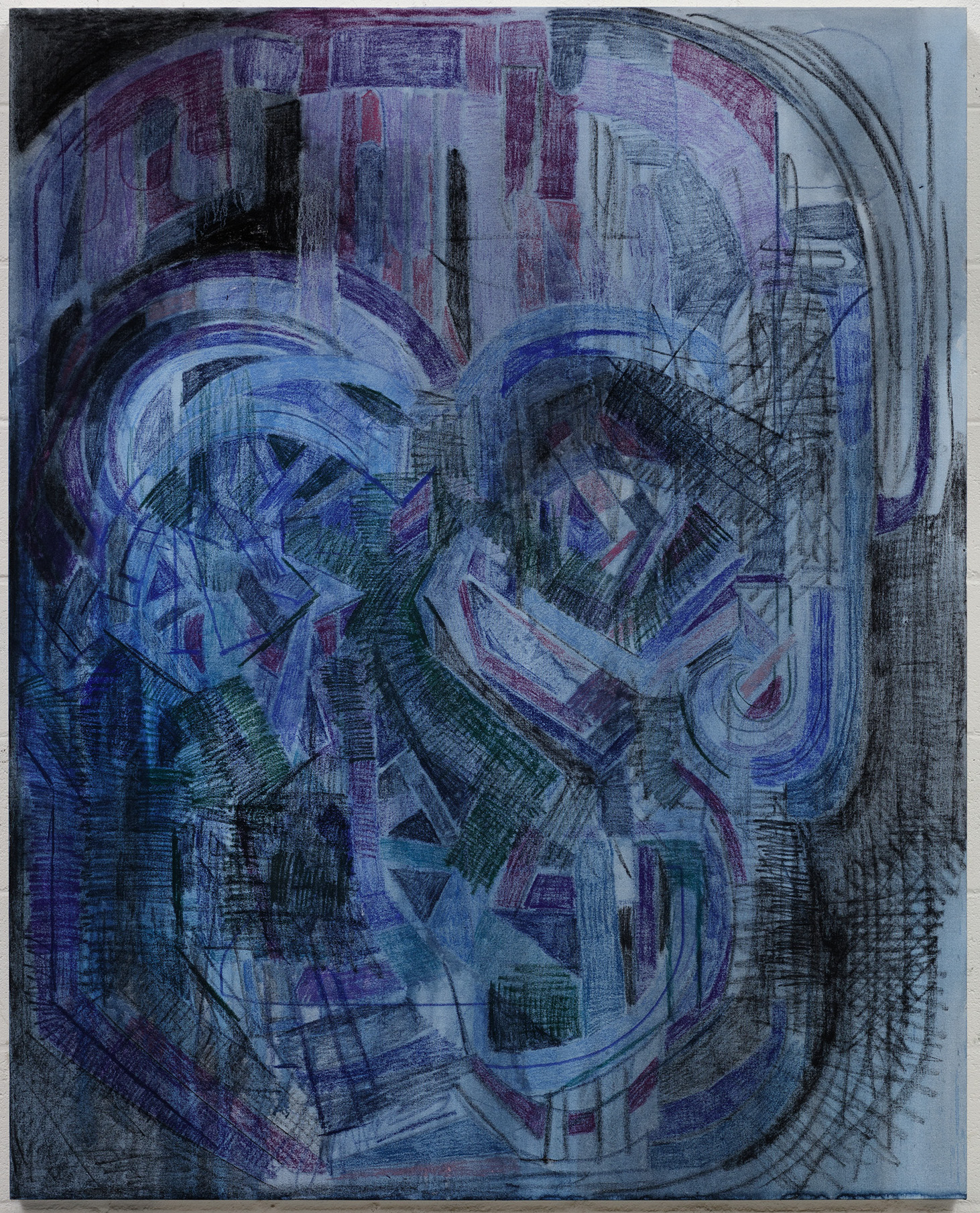

Thomas Houseago. © Thomas Houseago. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Adrian Gaut.

Thomas Houseago, who was born in Leeds, England, but now lives and works in Los Angeles, is an artist of great energy known for his large scale sculpture.

His work is often figurative, conveying both force and frailty through varied materials: carved wood, clay, bronze, steel rods, concrete, and hessian. This year he started showing paintings, after overcoming a long-standing inhibition to be seen as a painter. His exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in Hong Kong, Psychedelic Brothers - Drawn Paintings, 27 May to 17 August), is his first dedicated to that medium only.

With his paintings out in the gallery space, he is revealing what happens in the studio (reported to be often accompanied by an Alice Coltrane soundtrack). Indeed, drawing has always been an essential part of his sculptural process; he sketches and paints before moulding and casting.

Some of these painted opuses were black paintings Houseago considered as failed ones, from which he needed to find a way out. 'They were too emotional, almost unbearable to handle', he recalls.

It is only when he saw his ten-year-old drawing rainbows that he realised colours would break some of the intensity of the black paintings. He allowed his children to use crayons over the black layers with him.

This series, the Psychedelic Brothers, shows large format colourful skulls made from geometrical forms in charcoal, painting, pastels and pencils. The brush strokes are energetic and vibrant, the compositions coarse yet abundant with details.

The artist sees the paintings as companions or even the brothers he never had, and in memoriam his father as he remembers him in his last hospital-days 'leaving this world emotionally and physically'.

My sculptures are very rarely a manifestation of power, they are power and vulnerability, statement and disillusion.

The works also represent a connection to art history via the symbolism of the skulls (incidentally Houseago describes a dream in which whilst boating, Picasso instructs him to be an artist).

'When you make sculpture you are making a monument to death' he says and references the early Greek Kouros sculptures that fascinate him for their representation of movement yet embodying stillness. 'I want the sculptures to be filled with kinetic energy' he says. That appears true of his paintings too.

Presenting this series as a whole for the first time, he spoke with Ocula about what makes him so engaged in his art, the notion of giving permission and embracing the self.

CSKI really wanted to ask you about music. You have already mentioned it by saying it is so loud in the studio people working there have to either go along with it or wear noise-cancelling headphones; I understand you love jazz: Alice Coltrane, Kamasi Washington, and Thundercat.

THI will tell you something about music that I rarely talk about. A piece of music is a mark in time, on rhythm, on beat and with chorus. It begins and it ends. When you are in an art studio the notion of time can get really weird and thrown out.

Music puts texture to it. Also, the use of music allows me to insulate myself from normality. I think normality can be a real poison when it comes to making art.

CSKWhat is normality?

THThe pressures of everyday life, what you are supposed to be doing, what seems important. Art has to somehow reject that. To be able to make art you should reject the feeling that you should be doing something important. So music measures the time, gives you support, structures you and also removes you.

CSKAre you a macho painter?

THNot at all. I come from a super macho culture. Leeds (the main city of Yorkshire in the north of England) is hyper macho, the fighting you know ... I grew up very scared by that.

But I also grew up around women: my mom and two sisters. No dad, no brothers. In the north of England the traditional industries were collapsing in the '70s, I watched the white male psyche go through this weird panic.

So I grew up with very strong and powerful women in that strong macho culture that was failing. I saw the vulnerability in there, the tragedy, and the dismemberment.

In a way my work deals with the male, the masculine, its energy, the violence, all these things. But if you actually look at it, particularly the sculptures, they are super broken, they are super fragile. At the back of them there is something oddly vulnerable.

My sculptures are very rarely a manifestation of power, they are power and vulnerability, statement and disillusion.

CSKYour paintings do seem ... stronger, standing firmer on the ground?

THYes, they absolutely are. The two-D work has that feeling of stability and clarity. But what I found about it having lived with them, is that it gets deceptive. The longer I am around them, the less clear they get—contrary to my sculptures. Also the harder it is to finish them; I can finish a sculpture quicker, with more certainty. The two-D work is more ... it refuses to stop.

CSKOn one hand you edit, on the other you add layers ... you mentioned with the black paintings there is a two step process: from the dark underneath to the colours on top. How do you build your images?

THI think we are in a trauma collectively about what things look like. I don't think we believe in photographs anymore.

Ever since the Iraqi war, I don't think we trust the media the way we used to, feeling more and more that it doesn't relay complexity. And so I believe that we are in a period of hyper access to images and yet frustration with what they give us, with what we receive.

As an artist you are in that dilemma, you can't avoid the impossibility of these two positions, of the images being everywhere, everything being accessible, knowing what everything looks like, and yet feeling increasingly uncertain.

CSKAnd so you work on perception?

THI think you end up working on perception as you have no choice, because you are your own test subject. For example, I am really interested by the face as subject.

What I can do with it in history, the face as image, in our world, looking at your face, the things I know about it and the things I don't. It is a relatively benign subject. I am more twisted now, but when I started at 16, at that age, assumptions were like quick sand. And so you start to see that dilemma in you. I wasn't able to put words on it then.

Now I am able to focus on words and meaning within my position, my artistic evolution. I think we struggle about the reality of how things look, how we deal with history and how things have been passed on to us. At the end of the day, in the act of creativity we are left with the idea of the act being more important than what you make. To me the sheer registering of uncertainty is really the key. It means that idle details can make an argument for what the face looks like.

CSKAre they faces of landscapes?

THOr architecture? I think of them a lot like architecture. And if you think about the faces in architecture you see things come up.

I am a super visual person, I do research constantly. By traveling, through computer, I am a lover and collector of books. I am almost constantly researching something; there is always something I am trying to make sense of. The connection about poetry and writing, architecture and art, drama and music. I am really seeing those things that are co-dependent; it really fascinates me.

CSKSpirituality?

THSpirituality, but also about giving each other permission. A drawing can give a building permission and then a building can give philosophy a position. Music gives permission to painting. Each field gives each other permission, and that to me is a huge social dimension. You actually do change the way people interact and think by putting art out into the world.

See, I grew up in a period in the nineties where art was seen as the enemy, but what I realised is that the act of creativity gives permission to much richer thoughts than the act of frantic manic necessity. So I stand for that now.

CSKGiving permission?

THYes, permission is really important because to make art you really have to go against everything. That is the truth. You have to go against your own survival at certain times. If you are making a work of art you are putting your energy into that; for most parts for most of my life that didn't lead to any financial gain.

CSKYou say that, but now you are represented by Larry Gagosian ...

THNow I make money. But you are always on the edge of a catastrophe as an artist because the more money you make the more you put back in, and the more crazy you get. For me an essential part about making money is like coming out. I am not a saver, so I am always on the brink of catastrophe, anyway financially.

Look at my projects from the last two years, such as the Moun Room at Hauser and Wirth [a large installation on show during the winter 2014-2015 comprised of three chambers contained within one another inviting on meditation upon movement and codes of behaviour in response to architecture. Made of plaster, hemp and iron rebar].

If you make money, you see yourself able to make something like that. It is more risk but also more space and I don't mean physical space but space to dream. Then you start thinking OMG maybe I could make a sculpture park. LA is like that, and it has the room, in London or New York you don't dream about these things the same way.

So permission is very important. Number one as a child: permission to make art, one moment you are allowed to make art and then it is taken from you.

'When you make sculpture you are making a monument to death'

When you realise that the most important thing is your own imperfection, that is the moment you get out of the idea of perfection in all its forms including overestimating what you can do. You get involved with your own perfect imperfection, the more you go into that the more you give permission to the people around you too.

To make the leap to create a work of art is very traumatic for most people. To think creatively is becoming increasingly traumatic. So these areas you need to give space to. I went through this period in L.A. realising than the amazing Hollywood cinema industry of the '60s was related to the beatniks, Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg.

They in turn looked into 1920s Dada. You realise that's permission again, all these unlikely zones of interaction between rock music and literary criticism for example, they are real.

It is a problem to think that things are simple and can be solved and understood simply. Everything coexists, it creates empathy. Political thought and artistic thought should be linked.

CSKWhat advice will you give to young artists especially when they receive criticism?

THI think getting criticism is really, really, really, really good and it is painful and there is no antidote. It doesn't matter if it is directed at the work itself. Mostly when people get angry, it is a projection of their own issues, or that they don't have the energy to do what you do. But the criticism intention is super important because that is how you handle your relationship to the world.

The idea of art I believe is not to entertain, that's only one of the aspects. It is about different use of the brain. Art is by its very nature a kind of waking up. If you had any significant moment with any work of art, any, it is a little like waking up. And there is a slight regret too, it makes you a little upset. Classic example is going to the Prado in Madrid. When you see Goya, you are freaked out because it is not what you expected, and you feel a bit mad about it. But it is very strong—that's the moment.

You are not entertained by art, you are thrown, you are like WTF! That's my experience. Even if I listen to an album, and I know it's great I am little freaked out. So criticism is a natural area. My advice is 'handle it and really take from it and really live with it'.

I get horrible criticism, always, always got very bad criticism. And it means that I've lived a long time, for some of my friends that everybody loved, some energy is taken away with that. You can really destroy someone with kindness, it is the worth. The tension is painful but exciting.

CSKIs painting a way of relief?

THPainting is a relief from the insanity of the sculpture and then the sculpture becomes a relief from the insanity of the painting. So the two go very well together. In sculpture you are always fighting gravity, material, space, all these super exhausting realities. Painting is ultimately all fantasy, it is all soul floating, so just when painting starts to make you feel nauseous ... you can rely on sculpture.

I began as a performance artist, you know, setting fire to my art school in the '90s. The action ... What I like about painting and sculpture is that they are the summation of a series of acts. You have done this activity, this dance and the result of these marks and these shapes is your movement. I am hyperphysical, I come from super trauma and super repression, so that's how you fight back. And then I really just love dance, music and all performative aspects.

When people see my studio they experience a tremendous sense of activity. And then there is resistance, resistance on how you are supposed to move. This current situation where movement is so dictated, you look at people moving like computer programmes, automated, like the buildings. If you make architecture from a computer's imagination it makes people act like automates.

So then movement and freedom of movement, and making mistakes, becomes much more traumatic. I see people going through the subway, if you mess up swiping your card people panic. Society processes movement a certain way, you have to move through it a certain way. Art is spastic, a complete mistake, it is responding to your nervous system, it has the potential to be anarchic.—[O]