Theater of the World: Art and China after 1989

Chen Zhen, Fu Dao/Fu Dao, (Upside-Down Buddha/Arrival at Good Fortune) (1997). Steel, bamboo, resin Buddha statues, washing machine, computer monitor, tires, bicycle, fan, chair, household appliances, other found objects, string.Courtesy Galleria Continua, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World (6 October 2017–7 January 2018) is a survey exhibition of 'Chinese contemporary art' that studiously avoids the phrase. Curated by Alexandra Munroe, Philip Tinari and Hou Hanru, it coils chronologically up the entirety of the Guggenheim Museum's rotunda.

Bisecting this spiral is Hong Kong video art pioneer Ellen Pau's Recycling Cinema (1999), positioned equidistant from the Tiananmen Square student protests and the Beijing Olympic Games, two events that frame the show's historical period.

Zips of red traverse a field of warm stripes under a blue rectangle. Soon, it becomes clear that we're watching vehicles speeding across a highway. Sometimes, the camera pans at a speed that matches a car, truck or motorcycle, and we get a glimpse of a form as each moves across the screen. In Pau's video, abstraction makes some things hard to see. The subject of this show, similarly, has become somewhat illegible behind the binary formulation of the show's title: 'Art and China'.

##### Ellen Pau, Recycling Cinema (1999). Colour video, with sound. 11 min 42 sec. Courtesy the artist.

For the unacquainted, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World is an inviting introduction into a canon. The standard way of telling this story is to neatly match every art event to a historical one. 1979 is the year that the sprawling outdoor exhibition of the Stars Art Group was staged.

This was followed by the outpouring of tacitly permitted protest posters on the Democracy Wall for China/Avant-Garde in 1989, a bizarre and spectacular survey exhibition that took over the National Art Museum of China, which preceded the Tiananmen Massacre by only a few months. 1997, and the handover of Hong Kong, followed by Macau in 1999, framed the seminal Beijing media art exhibition Post-Sense Sensibility.

These two threads—the artistic and the political—seemed to intertwine neatly in 2008 with the spectacle of the Beijing Olympics, where Ai Weiwei unveiled the Bird's Nest and Cai Guo-Qiang designed the Opening Ceremony fireworks.

The curators tell this story with notes of skepticism. Alongside the artworks, they have interspersed documentary materials and a few surprise inclusions that help the viewer understand not just the story, but also the way it came to be.

The picture that emerges in the gap between the art and the archive is not free of tension, but the antagonisms enable the viewer to peer past the all-too-easy allegory of Chinese art as heroic resistance to the state: 'art versus China'. Yet, though this master narrative of 'art versus China' is shot through with other antagonisms, the exhibition is unable to completely escape it.

In the catalogue, Tinari notes that 'an easy narrative needs a boom at its beginning'. This exhibition begins, instead, with a bang: Xiao Lu's Dialogue (1989), included not as an installation but as a video still in a slideshow at the base of the Guggenheim's spiral. Life-size photographs of a young man and woman, backs turned, are affixed to two photo booths. They are separated by a mirror and a telephone off the hook.

The performance is perhaps better remembered than the installation: at the opening of China/Avant-Garde at the National Museum of China in 1989, without permission or warning, Xiao fired two bullets into the mirror from a borrowed pistol. In some ways it is fitting that the original work was not included, since most people have come to learn of it through rumour or press.

Usually, Dialogue is read as an artistic reflection on modernity's violent rupture. Yet Xiao has repeatedly stated that it was her response to a rape she endured as a teenager, committed by her parents' best friend. The performance was an expression of her feelings of isolation, rage and depression in the aftermath. The shadow that Dialogue cast on Xiao's biography is a good example of how the stories of artistic rebellion can often hide more than they show. 'After the gunshots,' curator Gao Minglu later noted, 'the interpretation of Dialogue no longer belonged to her, but to society'.

While some see an omen of the June Fourth Incident in the performance, which took place two months later, it might be more fitting to see Dialogue as a foretaste of the overshadowing of Xiao's own voice—that is, of how her intentions, as a survivor of sexual assault and dispossessed artist, were violently forced to serve a master narrative about the antagonism between artist and state. The curators of the Guggenheim exhibition did not provide this context—perhaps they felt it was not relevant. But it at least affords a chance to hone in on the overdetermined, overarching story of the artist as anti-authoritarian hero, and trace other plots.

From the first set of works clustered around the seminal 1989 China/Avant-garde exhibition, the show launches straight into the 1990s. This decade was marked by the withering of old socialities, such as class and work-unit (danwei), even as older forms like the patriarchal family were re-established.

Two works by Lin Tianmiao and Yin Xiuzhen, placed side by side, suggest how artists responded to the return of the domestic. In Sewing (1997), Lin wrapped a socialist-era sewing machine completely in white thread, and projected a video of two hands running cloth through it onto the machine bed. It is as if the machine, made useless, is haunted by its own functionality.

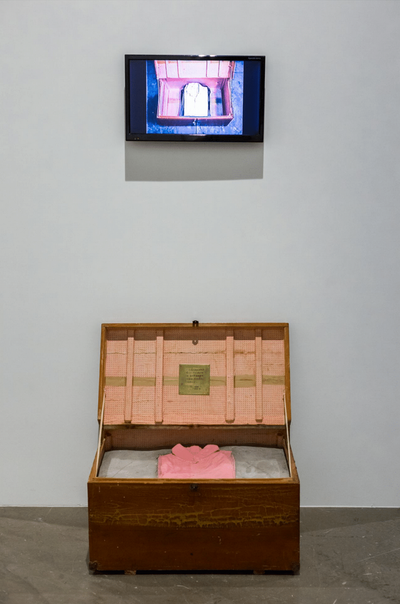

Similarly, Yin's Dress Box (1995) was made by stacking clothes accumulated from childhood to the present day in an old suitcase. She then filled it with cement and affixed a plaque of explanation on the interior of the case's cover. Here, too, everyday things lose their use and become, quite literally, hard to access. Although Yin uses materiality to mourn personal childhood memories rather than generic labour processes, for both artists simple things turn out to be rather ghostly.

Just as Xiao insisted that her work was primarily based on personal experiences rather than political abstractions, both Lin and Yin chose to work from intuition. Lin, in particular, has expressed a suspicion of intellectually-driven artwork, describing her method instead as 'a continuous touch'.

Yin, on the other hand, has been more circumspect, describing her work in terms of 'an indescribable feeling.' For an approach that, in other ways, was overbearingly discursive and produced torrents of theoretical debate, how are we to interpret this resistance to and evasion of theory?

Liao Wen, an art critic active in the debates around art in the 1990s, helps us with this question. (Her work appears time and again in the catalogues, magazines and books housed in the black vitrines dotting the rotunda.) A former editor of the experimentally-inclined Meishubao, she published in the late 1990s a monograph entitled Feminism as a Method, which observed this recourse to feeling by a generation of women artists and hypothesised (under the influence of Western feminist theory) that it was partly a resistance to masculinist intellectualism.

Her key point bears repeating: 'Unlike masculine discourse, which tends to prioritise a rational, abstract treatment of sociocultural problems, women's methods (nuxing fangshi) collectively express a consistent inclination toward, or even obsession with, an awareness of life and, relatedly, with the body, reproduction, experience and sensation.'

Liao framed this turn from social abstractions to the concrete realities of lived experience using theories that understood the personal as political. Following her lead, this turn to on-the-ground realities was also a response to the epistemological uncertainties of the political moment.

After all, the radical pragmatism of Deng Xiaoping was best summed in his statement, 'practice is the sole criterion for testing truth.' For a generation accustomed to ideology as the main motive, this new mantra was a shock; it did away with revolutionary beliefs (whether communist or liberal), and replaced them with the vague term 'practice'. I tend to view the interest of artists like Yin and Lin in bodily sensation and personal memory as a response to the depoliticising programme of Dengist China, and an attempt to understand through touch and feeling what exactly 'practice' might be.

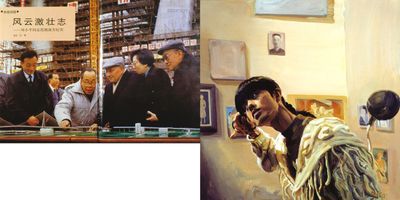

The work of Yu Hong featured prominently in the next section of the Guggenheim show, with a piece from the series 'Witness to Growth' (1999-present) helping to clarify the relationship between artistic practice and social reality. For each piece in this series, Yu coupled a public document and a painting she made based on the same year.

In one pairing, central planners are photographed refashioning Shanghai, while Yu paints herself clipping her fringe. These two events, in hindsight, appear both inseparable and complicit. Two makeovers, one executed at the highest level of the state, and another based on the personal experience of the citizen.

The source of the painted image, however, complicates this symmetry. As the wall label indicates, the painting is based on a still from the 1993 indie classic The Days (Dongchun de Rizi), starring Yu and her husband as thinly veiled versions of themselves. 'They were an ordinary couple. There wasn't anything to remember,' goes the opening voiceover. Her husband plays a painter, true to his life off-screen, albeit somewhat more tortured.

She, however, is reduced to the role of a muse. (She was widely known as a painting prodigy.) Given this background, the fact that she has chosen to paint this film still seems to suggest a reassertion of her artistic mastery. Pointedly, the image is rendered not in the original black and white but in full colour, as if she is fleshing out the picture more fully. Circumstance forced the artist to wrest self-representation from her male peers, through which the myth of the artist (invariably a man) erases an artist (often not a man).

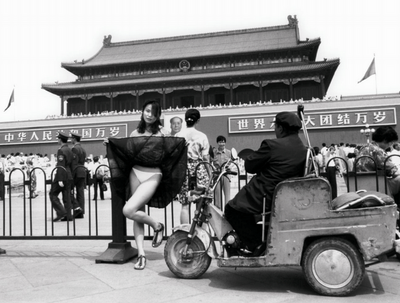

The problem here is not one of participation, but of recognition, with misrecognition constituting one of the subjects of the image June 1994, a small photograph tucked into a corner in the next section of this exhibition. To make the image, the artist Lu Qing and her separated husband Ai Weiwei went to Tiananmen Square on the fifth anniversary of the massacre, where Lu proceeded to flash the camera by lifting up her skirt. Two people look into the camera—there is Lu Qing, flashing the lens, and the impassive Mao right beside her.

This photograph is always interpreted as a political statement. Yet it could also be seen simply as a moment of flirtation. The love-hate relationship of the heroic artist and the state perhaps makes it harder to see the other artist, in plain sight—Lu Qing is never co-credited as an author of this image. (As an artist, her work involves meditative painting of grids on long scrolls, and has an affinity to some of Lin's work.)

But the work's authorship is less important than what Lu's overexposed absence from the label, the exhibition, and art history suggest. The script that we see in Art and China after 1989, in other words, is well-rehearsed. After all, every palimpsest—Tinari's preferred term for Chinese contemporary art history—is an accumulation of erasures.

A response to such erasures is a find-and-replace operation that infuses Kan Xuan's short video, Kan Xuan! Ai! (1999), which records her rushing down a crowded underpass hailing herself—'Ai!' is an idiomatic phrase like 'Hey!' Passersby stare at Kan and seek out her addressee, but her call is its own response. The subject calls after herself, in a chase that unfolds internally to one person rather than between two.

Although not included in Wu's seminal 1999 show Post-Sense Sensibility (Hou Ganxing), Kan Xuan, included in the section of the exhibition framed around this history, recorded some of the primary footage we have of projects on view in this collection of groundbreaking video, media and performance artworks. The slippery concept of 'post-sense' in the title is perhaps best characterised as conceptualism that was antagonistic to its own conceptualism. Artists under this rubric stayed away from clever concepts and instead opted to startle viewers with indescribable and unusual situations.

Moving on from Post-Sensibility, the relation between sensation and subjectivity changed as media technologies spread within China. Seminal curator Wu Meichun, whose exhibitions are featured prominently in the archives of the show, was the first to link the problems of 'feeling' to media technologies.

In the 1996 catalogue essay for her seminal exhibition Image and Phenomena, she insists that new media tools are not only a way to replicate passive consumerism but a means to harness an artist's capability for 'profound feeling and thinking' to change the world. As she puts it: 'contemporary art is absolutely not a camera, even when it uses a camera'. The problem in discourse on Chinese contemporary art has always been a myopic focus on the big picture—artists thus provided a way to rethink the relationship between the part and the whole, the local and the universal.

This was the case with the final work in the entire exhibition, which was supposed to be Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003): a video of a performance by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, where seven pairs of pitbulls leashed to custom treadmills lunge and snap at each other without ever making contact. Replacing this video documentation is a modest television set kept conspicuously blank—the work was pulled from the exhibition due to animal rights-based protests against the video's violent content.

Yet, the artist duo has consistently insisted that neither this work nor their practice is directly about violence. For them, the term 'animal cruelty' obscures the real object of discomfort, which is repulsion to the instincts that humans have carefully bred—here, the instinct to fight, which has been denied to the animals in the performance. The original petition on Change.org, interestingly, grasped this distinction: insofar as it stated that the restraints used in the performance cause a 'stressful and frustrating experience for animals trained to fight.' What's violent isn't the fighting, but its denial.

This kind of carefully constructed paradox is typical of the duo's work, which has often sought to invert and subvert usual binaries. It is also a product of their commitment to rigorous collaboration. As Peng Yu says of their early practice: 'We were getting married, but that's not an entirely happy thing ... We had to spend our lives face to face, growing and maturing together'. The intimate antagonism of Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other might perhaps be understood as a reflection on the complexity of a true 'face to face' relationship—the encounter with another who is neither self nor other.

It is perhaps fitting, then, that the show itself ends in uneasy silence. By making antagonisms visible, viewers at least have a chance to work through them. Sometimes it feels like the project that inhabits the discourse of Chinese contemporary art is doomed to an endless game of rock, paper, scissors in which the attempt to do justice to the terms, 'art', 'China', and 'the world' is self-defeating.

Yet, Art and China after 1989 is knowingly animated by these big bad concepts which, to the curators' credit, makes it easier to critique the all-or-nothing relationships between China and the world, artist and state, individual and collective.—[O]