Huguette Caland: A Movement of Her Own

Exhibition view: Huguette Caland: Faces and Places, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha (2 August–30 November 2020). Courtesy Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art.

In 2013, at the age of 82, Huguette Caland returned to her birthplace of Lebanon after leaving in 1970 for Paris, and staged her first retrospective at the Beirut Exhibition Center.

Curated by her daughter Brigitte, a professor of Semitic languages at the American University of Beirut, and Nadine Begdache, daughter of Janine Rubeiz, founder of Dar El Fan, the show revolved around Caland's first painting, Red Sun: a monochromatic bullseye of red orbs created in 1964 upon the death of her father Bechara El-Khoury, Lebanon's first post-independence president.

Red Sun is at once 'a ruminative elegy' and 'the defiant act of a thirty-three-year-old woman announcing the start of a new life', writes essayist Kaelen Wilson-Goldie.[1] Indeed, the catalogue for Caland's first solo exhibition in 1970 at Dar El Fan titles the painting Cancer or Starting Point.[2] After her father's death, Caland, a married mother of three, enrolled as an art student at the American University in Beirut, building a studio facing the sea at the end of her family property in Kaslik.[3]

It was apparently at her own dinner party that Caland announced plans to leave Lebanon six years later—and in turn, her husband and teenage children—'to pursue her art.'[4] 'I wanted to have my own identity', she said of her decision. 'In Lebanon, I was the daughter of, wife of, mother of, sister of. It was such a freedom to wake up all by myself in Paris. I needed to stretch.'[5] And stretch she did.

In Paris, Caland's lines and shapes, which in Beirut relied on heavy black outlines, became more refined, often delineated by gradated monochrome edges. She embarked on the 'Bribes de Corps' (Body Parts) (c. 1972–1975) paintings, characterised by curvaceous forms hinting at parts of the body, like buttocks, lips, and legs.

Two 1973 self-portraits from the series consist of image planes flush with a single colour—in one, a warm yellow, in the other, a fleshy pink—save for a delicate slit opening up to a lighter shade at the bottom of each.

Other paintings from that year include yellow, leg-like forms rising up against a brilliant, Mediterranean blue; and two grey globules pushing up against each other, like flesh on flesh. In one 1979 work, a pair of white testicular bulbs radiating edges of fiery red nestle at the cleft of buttery cheeks.

Ink on paper works from the 'Bribes de Corps' series are even more suggestive. One 1971 drawing is a delicate tracing of contours: a minimalist map of a valley, perhaps, or a woman's genitals—a demonstration of Caland's uninhibited command of the tensions between abstraction and figuration, at once knowingly teasing and elegantly forthright.

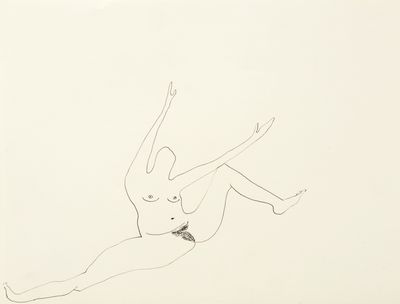

As Caland once stated, 'Art is not a part of my life; it is my whole life', and 'there is no life without some form of eroticism'. A 1973 drawing of a naked female figure with arms held high and legs akimbo is an unflinching celebration of this position, a liberated wink and smile contained in the title: Hi!

'My lines tell a story of my life,' Caland once explained; 'of people I met along the way, whom I loved and found and even lost...'[6] In the 1972 'Flirt' series, free-flowing yet precise trails dance lightly across the paper, scoring faces pressed up against faces—evocative depictions executed beautifully in a 1976 painting with two circles for nostrils and two red lips separated by a smooth stroke.

Caland 'was a movement of her own', Al-Thani notes. She knew how to live her present passionately, but had a distinct sense for the future.'

These contours found their way onto kaftans that Caland designed and wore, creating bespoke mannequins to model them, too—garments that rejected the trend for form-fitting western dress at the time, while fully celebrating the female form. Early examples include Tête à tête (Face to Face) (1971), a face-off between two profiles, and Miroir (Mirror) (1974), the outline of a naked body complete with a thick triangular mound of pubic hair.

Famously, Pierre Cardin saw Caland in one of her garments in 1979 and said he liked what she was wearing. She agreed.[7] Caland ended up creating 'Nour' for the designer, a line of over 100 kaftans, some of which were presented in Caland's first institutional solo show in 2018 at the Institute of Arab & Islamic Art in New York, alongside the first she ever made in 1964, just one week after her father's passing: black, purple, red, and orange stripes covered in line drawings that signal what was to come.

It is this first kaftan that forms the starting point for Faces and Places, Caland's largest exhibition to date at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha (2 August–30 November 2020): 'the first example', explains curator Mohammed Al-Thani, the Institute of Arab & Islamic Art's founding director, 'in which we see Caland address the female figure.'

Astonishingly, Caland only gained widespread institutional recognition in the last decade, with participation in the 2012 group show Le corps découvert at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the 2014 Prospect New Orleans triennial. In 2016, curators Aram Moshayedi and Hamza Walker effectively staged a mini-retrospective as part of the Hammer Museum's 2016 edition of the biennial Made in L.A., through which Caland emerged, at the age of 85, a break-out star. Among works surveyed was a 1988 portrait of West Coast artist Ed Moses, whom Caland befriended after arriving in California in 1987.

Participation in the 2017 Venice Biennale and 2019 Sharjah Biennial followed, with Caland's first museum show in the U.K., a 2019 retrospective curated by Anne Barlow covering her years in Beirut and Paris at Tate St. Ives, closing just before the artist's death.

Faces and Places picks up where the Tate exhibition left off, marking the first time that Caland's practice is being explored across all three contexts that defined her life.

California, after all, triggered a distinctive shift. While earlier works pointed to the multitudes inhabiting living bodies—such as those from the 'Parenthèse' (Parenthesis) series (1971), in which faces and figures are 'revealed' behind 'cracks' drawn into the image plane—later pieces invoke the traditions of carpet weaving, with marks building across surfaces like cross stitches telling stories.

Caland connected these later works with the rugs that surrounded her growing up in her parent's house in Lebanon.[8] Never before seen mixed media pieces in the Mathaf show echo this memory. Mustache Green Faces (2011), for example, is centred around two profiles joined like two halves of the moon, their noses combining to form a central yellow diamond. Bordering the scene like an entablature are rows of metope-like windows filled with cascading shapes, lines, and in some cases, homes.

Lebanon was never far from Caland's mind. In 1978, she painted portraits of her mother and father floating on blue waves (My Parents), while in 1981 she depicted faces emerging from the body of an amputee in response to the Lebanese Civil War. Titled Guerre Incivile (Uncivil War), the painting is a clear political statement—like the lesser-known fact that Caland founded the organisation Inash some 50 years ago, which continues to train and employ Palestinian refugee women in Lebanon to create and sell embroidered products.

But while she came from a political family and saw art as politics and politics as an art,[9] Caland's work was invested in a more transcendent pursuit of freedom as an embodied experience. 'She was a movement of her own', Al-Thani notes, 'She knew how to live her present passionately, but had a distinct sense for the future.' To live courageously was the action.—[O]

[1] Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, 'Huguette Caland: Beirut Exhibition Center', Artforum, May 2013, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201305/huguette-caland-40557.

[2] Huguette Caland, Tate St Ives, exhibition catalogue, edited by Anne Barlow, Sara Matson, and Giles Jackson (Tate Publishing, 2020), p. 6.

[3] 'Rewind: Huguette Caland as Told by Brigitte Caland', Art Dubai, 8 August 2017, https://www.artdubai.ae/blog/rewind-huguette-caland-as-told-by-brigitte-caland/.

[4] Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, 'Huguette Caland: Beirut Exhibition Center', Artforum, May 2013, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201305/huguette-caland-40557.

[5] Katharine Q. Seelye, 'Huguette Caland, 88, Dies; Celebrated Freedom in Art and Life', New York Times, 30 September 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/30/arts/huguette-caland-dead.html.

[6] Ricardo Karam, 'From Brigitte to Huguette Caland', YouTube, 17 March 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvVGyResalk.

[7] As told to Ricardo Karam in 'From Brigitte to Huguette Caland', YouTube, 17 March 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvVGyResalk.

[8] BiennaleChannel, 'Biennale Arte 2017 – Huguette Caland', YouTube, 11 February 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xjx_SeewsKA.

[9] Elisa Pierandrei, 'Lebanese artist Huguette Caland's provocations – artist profile', Art Radar, 15 July 2018, https://artradarjournal.com/2018/07/15/lebanese-artist-huguette-calands-provocations-artist-profile/.