Matthew Arthur Williams Archives a Dispersed Identity

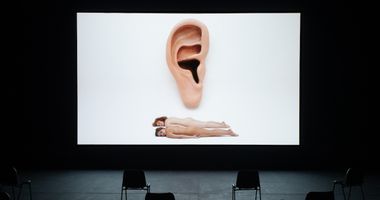

Exhibition view: Matthew Arthur Williams, Soon Come, Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA), Dundee (10 December 2022–26 March 2023). Courtesy the artist and DCA. Photo: Ruth Clark.

In Jamaican Patois, the phrase 'soon come' communicates an impending return or arrival, often with no fixed date. Charmingly vague and heavy with potential, it also forms the title of artist Matthew Arthur Williams' first major U.K. institutional exhibition at Dundee Contemporary Arts.

Spanning two galleries, Soon Come comprises black-and-white photography and a two-channel film with an accompanying sound installation, curated by Eoin Dara. It opens with a nude self-portrait, Untitled I (2022)—one of three self-portraits interspersed across the galleries at thresholds: the entrance, a corner, and the exit.

Untitled II and Untitled III (both 2022) likewise depict the artist in explicitly queer terms, acting like coded nods to the knotty relations between queerness and Empire.

'I hope it's very transparent like that,' says Williams when asked whether queerness informs the self-portraiture. 'You can't shield or cover up any of those intricacies of somebody's identities because we're talking about a certain subject matter—these things all come together.'

From the outset, it is clear that biography is the thing at stake in this unfolding of Williams' practice. Across the show's two rooms, we find documents surrounding the artist and his family's histories from a largely personal archive. Vintage pin badges from the Road Operators Safety Council punctuate the displays, telling a tale of migration, labour, and missold dreams.

A curatorial choice in Gallery 2 provides other cryptic clues to enrich this expansive landscape, which is both personal and collectively historical. Placed in pairs, the artist's photographs from Jamaica and Stoke-on-Trent are pasted inside hanging glass cabinets with yellow interiors, which combine with the black ink of the prints and the surrounding green walls to create the impression of a Jamaican flag.

'I think I held back from making work like this for a long time,' Williams admits. Indeed, until now, he has often kept himself at a slight remove, making this foray into family especially momentous. All the more so when one accounts for his prolific documentation of other Black artists in his circle, such as Alberta Whittle, Ingrid Pollard and Ajamu X, whose conversation with Williams features in his film, also entitled Soon Come (2022).

Granted, Williams' previous work grappled with urban-rural complexities and shared common ground with a cool pace and psycho-geographic inflections. But in this new body of work, he leaves the photographer-as-author behind, instead referencing his life-world directly.

Born and raised in London, the artist explores his relationship with Middle England, unearthing what his grandparents, parents and their peers experienced when granted U.K. citizenship. As one male voice recounts in the film, Soon Come (2022), a 'colour bar' scuppered his plans to become a builder. Settling instead for work in a local pit, the first-generation migrant remembers his misguided elation to enter what was supposed to be the 'mother country'.

Splicing newspaper cuttings, private conversation recordings, and public footage, the film deploys biography as a tool to voice an often forgotten archive, with personal narratives and media sure to resonate with a wider West Indies consciousness. It's compelling. Between scintillating snares, panning scenes of industrial graft and red-brick buildings typical to such working-class regions, we are invited to consider how labour intersects with race and class.

At one point, Williams' mother remembers the day she left Jamaica, telling her classmates she was bound for England. She later laughs about the number of people in her community who had said that they would only be in the country for a few years before returning.

Of course, this get-rich-quick scheme never amounted to its promise. As the artist notes, when 'you don't have the opportunity to go back, a term like "soon come" no longer just means, "oh, yeah, mi soon come", it keeps expanding.'

Embracing this fluidity of Caribbean identity, Williams' work makes a valuable addition to a long lineage of Black cultural studies, paying heed to the ever-contested status of West Indies diaspora, or what cultural theorist Stuart Hall described as, 'living in a place where the centre is always somewhere else.'1

Taking the issue further and complicating it with his own regional and metropolitan attachments, the artist demonstrates how terms like 'urban' or 'rural' are deciphered as much by a physical reality as they are a subject's position. In this vein, Williams carefully crops shots in an uncanny play on perspective. The image To Let (2022), for example, shows a typical midland street with the rural backdrop looming ahead, at once within grasp and inaccessible.

That said, Williams balances his work with heart-warming resilience, tactfully showing the sense of longing and displacement inherent to diaspora. One high-contrast photograph depicting his uncle, Q. Henry (2022), illustrates this skill. In the background is an out-of-focus garden with pegs on a clothesline glinting in the sun; in the foreground, a man stands stoically, dressed in a Superman t-shirt which reads, 'This looks like a job for...'

In the wake of a pandemic that saw terms like 'everyday heroes' emerge before a swift lapse in media memory, such images create honest and elegant idols of an invisible workforce. Performing a kind of memory work in real time, these documents form the lifeblood of Williams' practice—a double act of artistry and archiving otherwise forgotten ephemera.

This means that much of Williams' work leaves one wondering what is private, personal, or public. But there lies his skill. By elevating the personal to the level of official history, he again troubles common-sense understandings of what matters.

Here, curatorial sleight of hand has worked in the artist's favour. Where Gallery 1 felt immediately personal to the artist, showcasing particular sites and family members in a brightened room, the darkened Gallery 2 and its hanging cabinets feel museological and less exclusive to Williams. Of course, these are his images on view—but in some ways, that's beside the point.

To this end, Hustler (2022) captures a whimsical boat whose name, 'Hustler', had amused the artist. Taken in 2003 on a shared family camera while holidaying in Jamaica, the resulting negative was later reworked by Williams, who would swap frames and print shots again and again, in experimentation with his family archive that reveals an archaeological obsession.

Fuelled by his belief in a living archive, Williams' insatiable curiosity and attunement to affect in biographical ephemera does not resolve postcolonial identity or the abstraction of labour. Instead, he forces a reckoning with these legacies and the resistance against them in post-war Britain. Rather than a cold, analytical dissection of historical scars, Williams asks audiences to feel their way around them. —[O]