The elusive David Hammons is an American artist best known for his use of unusual and discarded materials, and his reinterpretation of cultural symbols to comment on contemporary African American experiences.

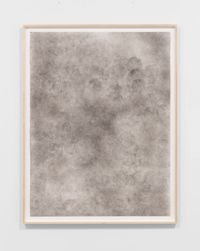

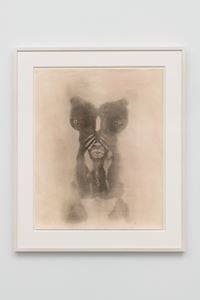

Read MoreDavid Hammons began his iconic 'Body Prints' in 1968, which were made by pressing greased body parts to a large sheet of paper and finishing the surface with powder pigments. Then a student at the Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, Hammons was also active in Los Angeles' Black Arts Movement, exploring the racial stereotypes imposed on African Americans in his work.

In David Hammons' artwork The Door (Admissions Office) (1969) from this period, imprints of hands and a face on a door with the words 'ADMISSIONS OFFICE' allude to the inaccessibility of higher education and educational inequality at large. In Injustice Case (1970), a man is gagged and bound to a chair—a reference to the treatment of Black Panthers co-founder and activist Bobby Seale in his 1969 trial.

In David Hammons' early artworks, the artist also directly challenges the use of racial language by employing the spade, which is a slur against African Americans. The symbol recurs in Hammons' 'Body Prints', including in Spade (Power for the Spade) (1969) and Three Spades (1971), and sculptures that transform used shovels into forms reminiscent of African masks, such as Spade with Chains (1973).

Following his relocation to New York in 1974, Hammons continued to make his 'Body Prints' while working with large-scale public sculptures and staging performances. Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983) saw the artist sell snowballs to pedestrians in New York, while the installation Higher Goals, at Brooklyn's Cadman Plaza Park (1986–1987), presented five telephone poles covered in bottle caps, with basketball hoops at the top, inspired by the fierce competition for spots on professional basketball teams.

Critics, including Calvin Tomkins in for The New Yorker in 2019, have often compared Hammons' practice to the work of earlier and contemporary artists. His 'Body Prints' reference Yves Klein's 'Anthropometries' of the early 1960s, in which women covered in blue paint made marks on paper. Hammons' use of abject materials draws parallels with Arte Povera, the radical Italian art movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, while his subversive anti-art tendencies recall Marcel Duchamp.

David Hammons has, in fact, cited Duchamp several times in his work. Around 1970, Hammons created Bag Lady in Flight—a sculpture constructed out of grease, shopping bags, and hair collected from a barbershop floor—which reimagines Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912). In 1990, Hammons nodded to Duchamp once more, installing urinals on trees near Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst in Ghent, Belgium, calling them Public Toilets.

Over the years, Hammons has produced influential and resonant artworks such as African-American Flag (1990). Initially made for the Black USA exhibition at Museum Overholland, Amsterdam, the work recreates the flag of the United States of America in red, black, and green—the colours of the Pan-African Flag. Since 2004, a version of the work has been flying outside The Studio Museum in Harlem, where Hammons was an artist-in-residence in 1980.

Hammons has remained aloof from art world institutions throughout his career, exhibiting only intermittently in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Rousing the Rubble, 1969–1990, his first major retrospective, was held at MoMA PS1 in 1990. The solo exhibition Concerto in Black and Blue (2002) at Ace Gallery, New York, was quintessential Hammons: the artist presented the empty gallery space, with all the lights turned off, as his artwork, and gave visitors blue flashlights to navigate the dark.

Other retrospective exhibitions include Five Decades at Mnuchin Gallery, New York (2016), and David Hammons at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles (2019), the latter of which was the largest solo presentation of Hammons' work to date.

Sherry Paik | Ocula | 2020