'Self-Interned, 1942': Isamu Noguchi and Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066

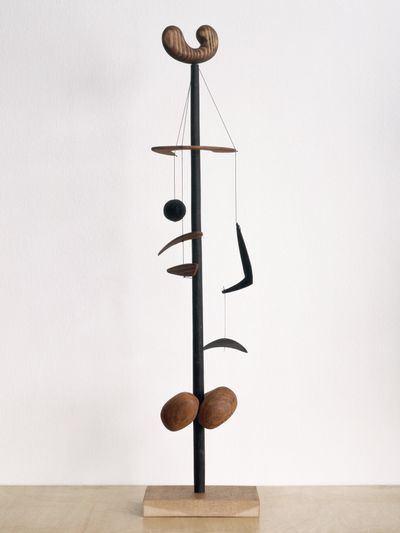

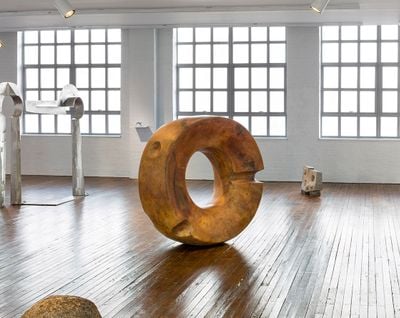

Installation view, Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center, on view through 7 January 2018 at The Noguchi Museum. Photo: Nicholas Knight/©The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, NY/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Dakin Hart, senior curator at The Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York—founded in 1985 to house the archive of Japanese-American sculptor and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi (1904—1988)—describes the museum's current exhibition, Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center, as 'a cultural history more than an exhibition of art.'

The show, which runs from 18 January 2017 to 7 January 2018 and features two dozen works accompanied by archival documents displayed in two large galleries, is particularly moving in the present political climate.

Self-Interned, 1942 explicitly focuses on Noguchi's personal experience of Executive Order 9066, which was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 19 February 1942. This order initiated one of the more shameful chapters in the history of the United States: the mass internment, without trial, of Japanese citizens and Americans of Japanese heritage along the United States' west coast.

Roosevelt's order came two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America's entry into World War II, and its racist undertow should not be ignored. The country was also at war with Germany and Italy, but detentions of German or Italian nationals were on a significantly smaller scale.

Although Noguchi was born in Los Angeles to a celebrated Japanese poet father, Yone Noguchi, and an American mother, he was not subject to the terms of the order as he was at the time a resident of New York, and not of the western states where detentions were enforced. In a remarkable decision, however, he decided to turn himself into the Poston War Relocation Center deep in the Arizona desert in May 1942. 'I wilfully became part of humanity uprooted', was how he described his decision in his 1968 autobiography, A Sculptor's World.

By then, Noguchi had studied with Gutzon Borglum in Connecticut, at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School in New York City, and with the Guggenheim Fellowship's support, he travelled to Paris in 1927, where he worked as an assistant to Constantin Brâncuși. In 1935 he designed his first set for Martha Graham's dance company, resulting in a collaboration that would endure for many years; and in 1940, he completed the bas-relief adorning the facade of 50 Rockefeller Center in New York City: a commission for what was then the Associated Press Building.

Noguchi's intentions in entering Poston were optimistic, to say the least. With hindsight, we might call them naïve. He felt deeply connected to his Japanese American fellows and aspired to add a positive aspect to their lives in forced displacement. With the encouragement of his friend John Collier, then commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, he dreamed that he might be able to redesign Poston as something more akin to a holiday camp than a prison, which is effectively what it was. He hoped that this would encourage the inmates to think of themselves less as victimised internees, and more as loyal and patriotic Americans.

But Noguchi failed utterly in this endeavour. Dakin Hart explains that Noguchi had gained the impression from multiple sources that he would have the support of the War Department, the War Relocation Authority, and the officers running the camp, but no support materialised.

After drawing utopian plans for a camp that would include a café-restaurant, a department store, a botanical garden, and a miniature golf course among other facilities, Noguchi swiftly realised his mistake. As Poston's sole voluntary inmate, he was regarded with suspicion by the authorities and distrust by the prisoners. After only two months at Poston, he decided to leave, though it was another five months before he was allowed to do so.

In November of 1942, Noguchi was granted a one-month furlough, but never returned to the camp. Although he was then granted permanent leave from Poston, this was followed by a deportation order. He was accused of espionage and endured lengthy scrutiny by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. (It took the intervention of the American Civil Liberties Union to bring this episode to a close.)

Self-Interned, 1942 approaches this history from three directions. First, it offers a grouping of Noguchi's sculptures in plaster, marble, bronze, wood and mixed media. Some are figurative, some semi-abstract, and others are abstract assemblages composed in a surrealist manner. These date from between 1941 and 1943—in other words, from the year before he entered Poston to the year after he returned to New York City.

This phase includes a plaster head of the theatre actress Lily Zietz (completed in 1941), the simplified features of which are reminiscent of Picasso's neoclassicism, and Mother and Child (1944—47), a carving in onyx, where the subjects are only vaguely suggested by a combination of smooth biomorphic forms. With totally different styles evident in this section, it becomes plain that Noguchi had yet to discover his own artistic personality. (Whether or not his internment affected his development thus remains a subject of speculation.)

Next, a series of display cases packed with correspondence and other documentary material are presented. The cases are organised by subject matter, and include documents and statements from the Japanese American groups that he worked with, a long unpublished essay that he wrote for Reader's Digest in 1942, and a statement that ran in The New Republic in 1943.

They also include correspondence with a supplier during the time when he was endeavouring to have a kiln installed at Poston, and letters to his friends and fellow artists. In one of these Poston letters, he tells Man Ray, 'This is the weirdest, most unreal situation—like in a dream ...' The blueprint of his 1942 plans for the park and recreation areas at Poston, mentioned above, are also displayed in the same room.

Finally, as a curatorial meditation on Noguchi's Poston experience and its impact on his artistic language, there are two groupings of his later sculptures made from the 1950s through to the 1980s. The first of these assemblies of work is categorised as 'Gateways', presented on one side of a gallery partition. This includes a welded and polished Doorway (1964) in stainless steel, and the six-foot-high Sentinel (1973), also in polished stainless steel, which suggests the outlines of an open door. The second grouping, shown on the other side of the partition, is called 'Deserts'.

It includes carved marble pieces like Double Red Mountain (1969), a low-lying carving in pink Persian travertine in which two smooth-topped swellings indicate the mountains of the title. There are also three iterations of Cactus Wind (1982—83): a foot high and nearly five-feet long welded sculptures in hot-dipped galvanized steel that sit on the gallery floor like long blades. These are clearly the creations of an artist far surer of his artistic personality. Despite differences in material, the works in these groupings share a confidence that is absent from his earlier pieces.

Even if this all makes for a satisfyingly multifaceted exhibition, the collection of works on view cannot help but reveal that, in the early 1940s, Noguchi was deeply uncertain of his artistic direction. He was in his late thirties and widely travelled: he had lived in Japan, spent time on both coasts of the United States and Indiana, made a 1941 cross-country road trip with Arshile Gorky, lived and worked in Paris and London, and had travelled the Trans-Siberian Railway to China and studied brush painting under Qi Baishi in Beijing.

Yet, Noguchi was not commercially successful, and his eventual celebrity was still years away. Immediately before his Poston experience, Noguchi already moved in a bizarre demimonde, supporting himself by creating stylised portrait heads of the rich and famous—the above mentioned bust of Lily Zietz being a case in point, though Ginger Rogers and Fernand Leger were also subjects.

Clearly though, Dakin Hart believes that Noguchi's seven months in the Arizona desert were profoundly important to the mature artist he became. In the exhibition text panel for the 'Deserts' and 'Gateways' installations, he writes that the desert landscape 'became a primary source of Noguchi's mental furniture: the ideas, concepts, and feelings around which he organised his personality and his work.' llustrating this in the 'Deserts' grouping are a number of untitled obsidian pieces from around 1980 that lie flat on the floor like long shards, and are carved to suggest that they might have been formed naturally.

Gone are portrait busts and surrealist-influenced construction—this is the work of an artist for whom abstraction is the most familiar territory. In the case of the 'Gateways' sculptures, material differences—stainless steel, bronze, and various types of stone, some circular, some angular—all share openings in their forms in common; the are gaps that we might imagine ourselves moving through. Dakin calls these forms Noguchi's 'artificial means of transporting himself to somewhere that, to him, felt like home.'

It is intriguing to ponder how much Noguchi's time confined in Poston might have contributed to this strand in his later work. If Dakin is correct in interpreting the works in 'Gateways' as sculptures that might offer their creator a means of traveling somewhere more congenial, then perhaps it was his time spent in the harsh conditions of Poston War Relocation Center that focused his desire to escape his immediate circumstances.

In his earlier work, then, we see an artist being many things, while later on, we see an artist turning to the complexity of the earth itself in order to find a reflection that matched, perhaps, his own need to find a way out of a cruel divide.'To be hybrid anticipates the future', Noguchi wrote at the beginning of the unpublished article he wrote in 1942 for Reader's Digest. 'This is America, the nation of all nationalities ... For us to fall into the Fascist line of race bigotry is to defeat our unique personality and strength.'

Self-Interned, 1942 was planned to coincide with February's 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. But the fact that the show opened the week of Donald Trump's inauguration, which was soon followed by the new president's notorious 27 January executive order restricting entry of nationals of seven predominantly Muslim countries to the United States, has given it new and poignant relevance, as we witness a re-enactment of policies very similar to those Noguchi experienced in 1942. —[O]