Whitney Biennial 2019: Between Resistance and Complicity

Nicole Eisenman, Museum Piece con Gas (2019). Plaster, wool, beeswax, epoxy, resin, fog machine and mixed media. Approximately 2.43 x 3.04 x 1.82 m (HxWxD). Courtesy the artist, Vielmetter Los Angeles, and Anton Kern Gallery. Photo: Object Studies.

The 2019 Whitney Biennial, is driven by a collective sentiment of sociopolitical consciousness, writes Banyi Huang in this reflection on the 79th instalment of the longest-running survey of American art.

The longest-running survey of American art, the 79th instalment of the Whitney Biennial (17 May–22 September 2019) is driven by a collective sentiment of sociopolitical consciousness. Curated by Whitney staff curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley, the exhibition draws on the work of 75 artists and collectives working in the United States. On view are a wide range of intimate, affective, and resistant articulations surrounding reconciliation, trauma, and resistance to the status quo, which, since the election of Trump, has involved waves of nationalism, xenophobia, and white supremacist violence.

Framing the entire show was a series of protests directed at the Whitney's Vice Chair Warren B. Kanders, which took place before the Biennial opened. Kanders is the CEO of Safariland, LLC, a manufacturer of law enforcement products, such as riot gear and tear gas, which have been used on the Mexico-U.S. border, and by the Ferguson, Oakland, and Baltimore police, to name a few examples. In November 2018, a report published on Hyperallergic highlighting this connection was followed by an open letter from Whitney staff members calling for Kanders' immediate removal from the museum board. In December 2018, participating artist Michael Rakowitz announced his withdrawal from the Biennial. A series of protests by activist collective Decolonize This Place followed, titled 'Nine Weeks of Art and Action', which ended with a final protest at the museum on the Biennial's opening on Friday 17 May.

Amidst the controversy, another thematic issue emerged out of the exhibition: what does it mean to hold an institution accountable? Institutional entities that occupy positions of privilege have increasingly come under fire for replicating insidious power structures through non-transparent operations. The Whitney Museum of American Art is no different, and its biennial exhibition has become a powerful site for impassioned confrontations. Most recently, the inclusion in the 2017 Biennial of Open Casket (2016), Dana Schutz's abstract painting of Emmett Till, an African-American boy falsely accused of making advances on a white woman and then brutally murdered, sparked bitter debates over race and representation.

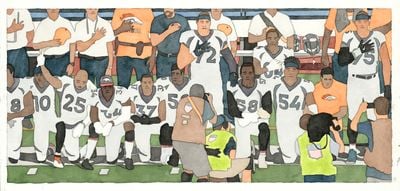

Resistance against oppressive institutional structures is referenced from this Biennial's outset, which opens on the museum's fifth floor with a digital animation by Kota Ezawa titled National Anthem (2018). Each frame is a hand-drawn watercolour rendered in a flattened and reductive style based on footage of NFL players kneeling during the the national anthem at the start of football games as a protest against police brutality and racial injustices in the United States. Set to a slow, melancholic soundtrack, the work stands not only as a testimonial to the volatility of the highly racialised, politicised, and mediatised landscape in the United States—it is also a poetic rendering of resilience in the face of power.

Nearby, Jeffrey Gibson's hanging installation became an active site for protest on the Biennial's opening night, when the Indigenous Womxn's Collective staged an intervention there. Under Gibson's elaborate garments adorned with colourful beads, fringes, and tin jingles, which draw from Native American traditional materials and handicraft techniques, the Collective appealed to the anti-colonial underpinnings of Gibson's sculptures by incorporating elements from the Ghost Dance, a messianic Native American movement that embodied pacifist resistance to invasive settler policies. The Indigenous Womxn's Collective called out the Whitney, which claims to stand in solidarity with Indigenous art, as a toxic accomplice to white supremacy due to its silent endorsement of Kanders, since Safariland-produced teargas has been used against Indigenous people protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock.

These protests all feed into Triple-Chaser (2019), Forensic Architecture's much-anticipated Biennial commission, a video that combines investigative journalism with machine learning to identify the deployment of the Triple-Chaser teargas canister produced by Safariland in online images and footage from across 14 countries, including the San Diego-Tijuana border in the U.S. and in Gaza, Palestine. In order to train a computer algorithm to recognise the canister, the team painstakingly constructed a digital model and placed it within different iterations of photorealistic and 'synthetic' environments. The result is not only an indictment of the double standards at play in an institutional exhibition like this, but an attempt at resisting such duplicity from within.

Perhaps such double standards could be attributed to degrees of temporalremoval at play in institutional exhibition practice. While it is permissible to exhibit art objects that obliquely touch upon historic genocides of colonial settlers, institutions are much less willing to address their direct culpability in current events.

A reconciliation between the passage of time and the processing of trauma is the subject of Tiona Nekkia McClodden's multi-channel video installation, I prayed to the wrong god for you (2019), projected on screens arranged into a triangular formation and suspended above sculptural artefacts. McClodden's video triptych pays tribute to Shango, a deity originally worshipped by the Yoruba tribe of Southwestern Nigeria, which thereafter migrated to the Caribbean and South America with the slave trade. In the videos, a self-initiated pilgrimage that negotiates externally imposed faith with internal affect unfolds; we see McClodden cutting down a cedar tree, carving tools, and engaging in invented rituals such as washing wood chips and dressing the wood in bandages. George Bernard Shaw's The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (1932), which charts a young African woman's quest for God, appears briefly in the video.

By forging a kinship to ancestry, ritual, and specific objects, McClodden approaches the legacies of exploitation and oppression as an ongoing struggle that cannot be collapsed into the past. Ilana Harris-Babou's video Reparation Hardware (2018) likewise invokes the notion of 'reparation', this time using marketing tropes in high-end home refurbishing that appeal to 'tastefulness', 'craftmanship', and 'timelessness'. In the video, Harris-Babou is seen caressing rugged wood planks, doodling in her notebook, and absurdly hitting nails with a clay hammer. The promise of nostalgia in aspirational furniture design and its salvaging of old materials, is turned on its head when the artist emphasises the significance of 'making it right'—that is, to address the inequality and complacency built into the state system, and acknowledge the enslavement and prolonged oppression of black people across time. The crumbling of the hammer, then, invariably points to the failure of the American dream.

Equally addressing systemically rooted injustices are Christine Sun Kim's series of charcoal drawings that capture various degrees of 'deaf rage'. Given individual titles such as Degrees of Deaf Rage within Educational Settings and Degrees of My Deaf Rage in the Art World (both 2018), the drawings give visibility to forms of discrimination towards deaf people in everyday, institutional, and art-world settings. Coupling sketches of pie charts depicting degrees of rage—'acute', 'obtuse', 'full-on'—with humorous captions stemming from the artist's own experiences, Kim expresses various ways in which needs of deaf people are silenced or suppressed, adopting fury as a mode of rejection over emotional repression or assimilation.

Contrasting with the sardonic humour in Kim's graphs are Elle Pérez's tender and hopeful photographic portraits of the LGBTQ community, showing in the same gallery. Images present subjects undergoing transformative processes such as getting gender reassignment surgeries. Vulnerable scenes refute the immutability of identity assignations and rigid categorisations. While Dahlia and David (fag with a scar that says dyke) (2019) juxtaposes the coldness of a scalpel above a leg with the warmness of the word 'DYKE' written in blood, Wilding and Charles (2019) show two subjects locked in intimate embrace, one gloved hand cupping a chest wrapped in clingfilm, indicative of a recent tattoo session.

Other works in the Biennial critique the Western canon, particularly modernist tropes that revolve around form and the male genius. Carissa Rodriguez tackles the modernist myth of origin and purity in The Maid (2018). Installed as a large-format projection, a video chronicles a selection of Sherrie Levine's reproductions of Brancusi's iconic sculpture, Newborn (1915), in various collection settings. Brancusi's original creation, first made in marble in 1915, was celebrated for its pristine ovoid shape, which he thought embodied the fragility of the newborn baby and the essence of form. Levine, known for her appropriative gestures, later cast the work in crystal and black glass, questioning the autonomy and originality espoused by 20th-century modernism. Rodriguez recirculates Levine's original intervention in film, documenting Levine's sleek, reflective egg-like forms in various homes, galleries, and museums before zooming out with aerial drone to show extravagant exteriors such as Manhattan high-rises or clifftop residences. An additional photograph by Rodriguez, All the Best Memories are Hers (2018), illustrates cryopreserved embryos, often used in tandem with in vitro fertilisation, further complicating points of origin with advanced reproductive bio-technology.

Situating Levine's—and by association Brancusi's—objects in dialogue with the act of repetition, biological reproduction, and the domestic sphere, Rodriguez's inversion of Brancusi's moment of origin, and by extension, aspirations towards vanguard originality, is echoed in Heji Shin's unapologetic, mid-format photographs depicting the very act of birth. While the opening of the mother's legs recalls Courbet's blasphemous painting The Origin of the World (1866), the bloody, wrinkled heads of babies in the birthing process is a far cry from Courbet's sexualised fantasy.

Extending this idea of biological and technical reproduction and its implications on the natural and technological sphere is Korakrit Arunanondchai's 23-minute film, with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4 (2017). Combining video essay with performance, this is a hallucinatory rumination on cosmological reincarnation that questions how memory can survive beyond the mortal body and the nightmarish present. Heavily layered montages see Arunanondchai engaging in philosophical exchanges with Chantri, a drone spirit elegantly voiced in French; the artist's grandmother, whose relationship to personal belongings is slowly affected by dementia; footage of the Women's March in Washington D.C. in January of 2017, and a dishevelled anthropomorphic rat that seems to exist in a parallel universe.

The complex sentiments towards political extremes, social inequality, and ecological degradation articulated in Arunanondchai's film, and in this edition of the Biennial in general, appear to culminate in Nicole Eisenman's outdoor kinetic sculpture, Procession (2019). On the museum's sixth floor terrace, larger-than-life figures made from plaster and discarded materials are assembled into a tableau of represented movement, with figures trudging forward, lugging heavy cargo, including a body on all fours as if in prayer or supplication.

With such details as steam blowing out of a character's orifice and gum stuck to another's feet, Procession mirrors the pervasive imagery of protest seen throughout the Biennial, while also questioning what it means to be a part of a community at a time when ideas of 'they' versus 'us' and 'mainstream' versus 'other' are prevalent, and neutrality implies a conscious, complicit choice. In the show, such divisions come across in various ways, from the organised protests that picketed the show, to the artists presenting investigative endeavours and self-searching journeys within it.

Among Eisenman's motley crew, one character stands out in particular. A small bird lies collapsed in a box, its talons slumped over the edge, as though the exhaustion of existing has proven all too much. Indeed, rest is needed, but the cycle of dissent and critical engagement must not—will not—stop.—[O]