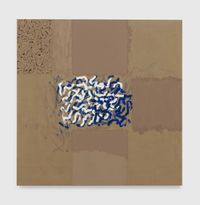

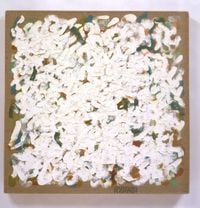

For over five decades, the painter Robert Ryman has dedicated himself to the study of white. Using a wide range of surfaces including fibreglass, metal and canvas, and a range of fastenings and layering techniques, Ryman uses this colour to make visible the materiality of paint and light.

Read MoreIn 1953, Ryman moved to New York with the initial aim of becoming a jazz musician. To support himself, he took up a job as a security guard for The Museum of Modern Art. There he was influenced by the art that he encountered daily—works by masters such as Matisse and Cézanne. He was also influenced by the time spent around his co-workers—the soon-to-be art legends Sol LeWitt and Dan Flavin.

For ten years after his arrival in New York, Ryman doggedly experimented with his chosen colour. His approach to painting mirrored his previous experience in jazz; the improvisations based on chords and scales in music became riffs based on light and surface in painting. It was a long time before his paintings would gain traction in the New York art scene, momentum that perhaps was slowed by the dominance at the time of Abstract Expressionism—a movement to which Ryman’s work was diametrically opposed. It was only in 1967 that he had his first solo exhibition. In 1969, he was included in Harald Szeemann's historic exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, and from there his career began to soar. Ryman is now considered one of the most significant founding fathers of both Minimalism and monochrome painting in the United States.

Ryman does not use white as a colour, but instead as a conduit to making things visible. Rather than using the medium of paint to escape into illusion, Ryman’s paintings are a means of focusing on the present. Emphasising a rejection of representational painting, he often paints on squares—a neutral space alluding neither to landscape nor to portrait.

Ryman also, however, rejects the category of abstraction. His paintings do not aim to abstract or reduce reality, but reveal the complexities of light in the spaces they inhabit. A work can be observed by the same viewer an infinite number of times and something previously unnoticed will be found upon each view. They are paintings that reward those who take time and pay attention.

During his retrospective at Dia:Chelsea in New York (9 December 2015–29 July 2016), director Jessica Morgan said of his work, ‘With Ryman, you find yourself walking very close to the wall’. In the rooms in which the paintings are situated, nuances of light influence the subtle ebb and flow of colour and shadow in each brush stroke, leading to a new revelation every moment.

Casey Carsel | Ocula | 2017