Artist Insight: David Diao

In a career spanning more than half a century David Diao has conducted a many-faceted exploration of the assumptions and comprehension of contemporary painting, which has been underpinned by vast erudition, a sharp critical intelligence, and a sustained sense of humour. Not surprisingly he enjoys a reputation as an insightful and stimulating speaker both on the subject of his own work and that of his predecessors. An autobiographical element that first appeared in his paintings in the early 1990s now sits at the front and centre of his work, focusing specifically on his Chinese heritage and his childhood years in Chengdu and Hong Kong. In his newest work this personal history features alongside his fascination with the artists and designers of the modernist tradition, and the ways in which their personalities informed their work. In the following interview, which took place at Diao's home and studio in the Tribeca neighbourhood of Manhattan, he talks about the work which was presented in Shanghai at West Bund Art & Design 2017 by ShanghART Gallery in collaboration with Postmasters Gallery.

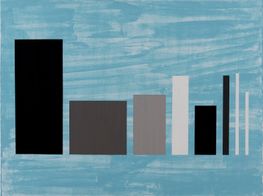

Installation view: David Diao, HongKong Boyhood, Postmasters Gallery, New York (4 February11 March 2017). Courtesy the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

Your last solo show here in New York was HongKong Boyhood at Postmasters Gallery (4 February–11 March 2017). What have you been working on since then?

HongKong Boyhood was a project that lasted a couple of years. In my mind it was a big project, because it was something I could sink my teeth into: the five years I spent in Hong Kong that seemed to demand some kind of treatment. As usual when I have a germ of an idea, I have no idea how to proceed, other than having a few snapshots in the mind. The first ones of that group went to Art Basel Hong Kong in 2016. Most of them were sold, so I ended up making similar ones to show at Postmasters in February. There were a good 25 paintings. After that, I felt a bit adrift without a particular subject to latch onto. That often happens to me. I don't have a programmatic approach to doing work.

And what happened next?

I always think of art making as a critical activity. The first critical activity is to think against yourself, to not be satisfied. Whatever you do, as good or successful as it might be, there's always a flip side to it. Oftentimes I go to what I didn't get to touch in one group of work in the subsequent work. It's so as not to waste the older work. To make the older work more intentional, more focused, more clear. So the newer work is an attempt to make more, to clarify.

Your work proceeds as a process of gradual clarification?

What every artist does is they don't want to throw away anything they've already done. You want to hold onto something. The first thing that came to my mind was the phrase 'shadows of forgotten ancestors'. This happens to be the title of a 1965 film by the Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, but mostly I was zeroing in on the textual meaning of the phrase 'shadows of forgotten ancestors'. I made a couple of paintings with that title.

And who are the ancestors that you're interested in?

Well, obviously there is already a roster of predecessors in my work. Whether it's [Barnett] Newman, or [Kasimir] Malevich, or [El] Lissitzky, these are people who have been important to me forever. I decided to dig back into using some of those as references again.

One of the key paintings in the West Bund show is called Actual Scale (2010). It's Malevich's black and red square painting in the MoMA collection, and which I've referenced many times in other works, and it's positioned as if it's on a grey wall. It's called Actual Scale because it's the actual size of the original painting. It's a way of framing that painting again.

That's what led me in another painting to frame a page of Lissitzky's letterhead on a piece of paper on an orange ground as if it's an orange desk or an orange wall. The letterhead is something trivial, but the letterhead actually employs his monogram which he also used in some of his major paintings. For him, it was something that's maybe just a throwaway, but it was very useful for him in his work.

You've used artists' monograms in your work before.

Yes, way back in the mid-1980s when the thought I had in mind was, 'What is it that gives authenticity to anybody's work?' It's the signature. I did a whole group of works blowing up signatures of artists and logos of groups of artists. One point I was trying to make back then was it's not a singular effort, it's a collective effort. The Bauhaus logo is as important as a Mondrian signature.

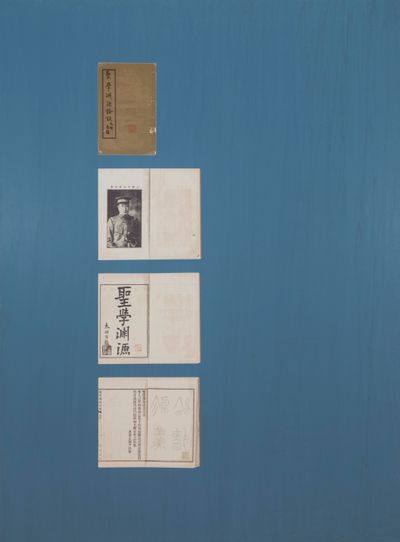

I'm intrigued by the painting called Maternal Grandfather's Book (2017). It seems to come from a different area of interest altogether.

I was still thinking about the phrase 'shadows of forgotten ancestors'. I'm not unknown at this point for bringing up references to my artistic forefathers, but having already done work that's directly autobiographical in the HongKong Boyhood works, why not actually bring in blood ancestors?

I happened to have a very famous maternal grandfather whose whole history was unknown to me until 1979 when I went back to China after 30 years absence. I didn't know very much about him other than the fact that he was this famous general and the person who ran Sichuan. My mother, who I saw for the first time after 30 years, gave me a book that my grandfather had written. It's a book on Confucian ethics. What was unknown to me was he was a horrible colonialist. He was the guy who put down the Tibetan rebellion in the 1920s. On the heels of the Mongolians declaring independence, the Tibetans wanted to do the same. My grandfather took his army, went there, and suppressed it, and named many cities along the way from Sichuan to Tibet after himself.

He sounds like a bizarre character.

He was actually a very learned guy. Back then, to achieve any kind of officialdom, you had to take the civil service exam. He was a prize winner in some of those exams and as a result was sent to Japan for military training. Already he was steeped in philosophy. Anyway, I said to myself, 'I really should do something with this,' so one of the works in this group is a painting with silkscreen, with the cover and various pages of the book.

It's fascinating how one painting provides the starting point for the next. Tell me about the paintings of furniture. How do they fit in?

There are paintings referencing my artistic forefathers and my personal forefathers. Then, I thought, 'Well, I'm already using logos of artists in the form of their monograms, what are other things that interest me?'

Architecture and furniture design are a big part of my life. I remembered that in 1999 I had made paintings of George Nelson's sling couch and Corbusier's chairs. When I was doing those I was thinking that in the images I have, the Corbusier Grand Confort chair looks kind of decrepit. It was a way to reference the fact that modernism doesn't stay fresh. It undergoes entropy and decay.

George Nelson designed a lot of these modernist pieces when he was at the furniture company Herman Miller. Nelson was a very polymathic designer. He had so many tentacles reaching into so many areas that he could be likened to the same kind of force as Malevich or Lissitzky in the field of design.

I brought out the earlier paintings of the chairs and the couches, and made new ones of the couch: not in its decrepit form, but of the resplendent, perfect, stainless steel substructure. Once I was doing that, it was a short jump to use the logo of Herman Miller, which happens to be one of the most beautiful logos ever designed. It's both a crown and an 'M' for Miller.

That logo features in a painting called _El Lissitzky/Herman Miller _(2017). What's going on there?

I realised that I had to make the painting interesting in terms of composition, in terms of colour, in terms of facture, in terms of the material presence. At the same time, I have a longstanding animus against the subjectivity of my own hand. This relates to my earlier critique of abstract expressionism, and the idea of the casual spontaneous mark communicating the genius of the painter. These things are so internalised in me that I'm actually rigid from fear of expressing too much. One way for me to get around that was—as long as I was dealing with Lissitzky anyway—to go to Lissitzky's work and actually overtly borrow design elements. It's very difficult for me to do a spontaneous mark, but I could go to a Lissitzky book and lift certain curves directly. That's where the curves in these paintings come from. —[O]