Thu Van Tran’s Material Metamorphoses

For artist Thu Van Tran, matter tells stories of contamination—it reveals landscapes that are composed of stains.

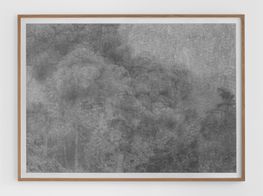

Thu Van Tran, Trail Dust (2021). Graphite on Canson paper. 100 x 150 cm. © Thu Van Tran. Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech.

Matter explodes when you really zoom in, with seemingly inert constitutions unmasking charged enmeshments of micro and macro histories that speak to the material conditions of life on earth.

In the case of Red Rubber (2017), which was shown at the 2017 Venice Biennale, rubber casts of a tree trunk from the Michelin plantation in Phú Riềng map the history of plantations in Vietnam, with the rubber plant having been introduced to Indochina in the 17th century by the French.

Among milky white rubber trunks laid horizontally on crates is a red one—a reference to Phú Riềng's other name: Màu Đỏ, or The Red, not just because of the colour of its soil, but for the rebellion that swelled there among Indigenous communities exploited by colonialists for their labour once the plantation was established in the 1920s. 'Communism in Vietnam has its roots in this period', the artist has pointed out.1

But as loaded as this material is, Tran finds poetry in its abstraction; that is, its transformation from matter to a work of art, poised for display so as to elicit engaged meditations on the complexities of the material legacies that not so much haunt the world as infuse it.

The formal abstraction drawn out from actual events is best articulated in works by the artist that confront the legacies of Trail Dust, a U.S. military operation intended to clear the Viet Cong's jungle hiding spots and supply routes using what was dubbed as 'rainbow herbicides' manufactured by Monsanto and Dow Chemical: Agents Green, Pink, Purple, Blue, White, and most notoriously, Orange.

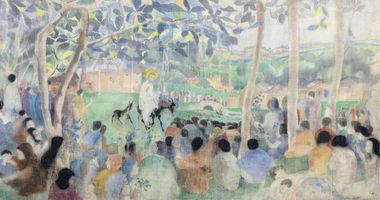

For the 'Colours of Grey' series (2012–ongoing), the artist takes pigments that correspond to these rainbow herbicides, and layers them on paper until they turn a layered, monochromatic grey, their edges functioning as an index of the work's real world references.

Fresco versions of this series formed part of an exhibition commemorating the life and work of French author Jean Giono at MUCEUM in 2019, and for the artist's presentation as Marcel Duchamp Prize nominee in 2018, onto which Si rien ne sort d'ici (If nothing comes out from this) (2018) was projected. The silent 16mm film is composed of four 'breaths': chapters including video of plaster casts broken to reveal the letters of the work's title, and footage of a volcanic eruption.

Thu Van Tran sees an act of voiding in 'Colours of Grey'; a mirroring of the destruction of Vietnamese land and people during the Vietnam War.

That material re-enactment happens again in the 'Rainbow Herbicides' series (2012–ongoing). Splatters of rainbow herbicide hues intervene like expressionist colour blocks over detailed large-scale graphite drawings of volcanic, atomic, and napalm explosions: a reflection of the oppositional scales of creative and destructive time, like the long stretch of a jungle's formation and the instantaneous snap of its man-made erasure.

There are no interventions in the graphite drawings lining the walls of the artist's latest exhibition with Almine Rech in Paris, Beyond the need for consolation (16 October–13 November 2021), save for their meditative depictions of explosions once again built up by repeated layering until smoky textures seem to rise up from the surface.

Thu Van Tran sees an act of voiding in 'Colours of Grey'; a mirroring of the destruction of Vietnamese land and people during the Vietnam War.

But while the plumes of the 'Dust Trail' series (2017–ongoing) depict actual phenomena—figurative representations of recognisable events—they become abstract in their repetitive presentation. That is, stand-ins for the concept of an explosion, whether natural or man-made, and its mimetic presence throughout human history, not to mention its effects on it.

That never-ending finality, of the destructive eruptions that have marked human and non-human lives, is perhaps where the question of consolation comes in, and the concept of being beyond it, per the show's title.

The 'Dust Trail' drawings frame a series of delicate porcelain sculptures positioned on plinths from the series 'Le génie qui redresse le ciel', or, 'The genius who straightens the sky' (2021).

Each sculpture looks like a stone, but at points, their mottled, mineralised, and marbled surfaces give way to folds that invoke fleshier lamella like forms—carvings that mark the transformation of inanimate surface to moving wing.

As the artist notes, these creases signify a folktale about one hundred black stones that transformed into silver birds one night on the shores of Hanoi's Lake of the Returned Sword, named after a sword gifted to Emperor Lê Lợi by the Dragon King to defeat the army of Ming China, which he later returned to a Golden Turtle God in the waters.

In this invocation of metamorphosis from inanimate to animate, death becomes rebirth—a détournement that reframes a landscape that has been occupied and brutalised as the place from which life begins again. —[O]

1 Chloe Chu, 'Thu Van Tran: The Materiality of Memory', interview published in Art Asia Pacific, Issue 121 (November–December 2020).