Lahore Biennale 02: Past Reminders, Possible Futures

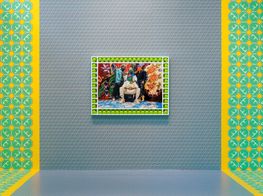

Works by Rasheed Araeen on view at between the sun and the moon, Lahore Biennale 02, National College of Arts, Lahore (26 January–29 February 2020). Courtesy Lahore Biennale Foundation.

The second Lahore Biennale, between the sun and the moon (26 January–29 February 2020), featured works by over 70 artists in 13 sites across the city that were built and used by three sovereigns—the Mughals, the British, and the postcolonial Pakistan state. In this constellation, three modes of governance and temporalities overlap and fold into one another.

Many of the Biennale locations were found near the Mall Road, where the British set up their administration to the south of the Mughal-built Lahore Fort, whose buildings the Pakistan state took over while adding cultural sites to symbolise its sovereignty—most notably, three sites within the colloquially known Gaddafi Stadium, a complex of sporting and cultural buildings with the Gaddafi cricket ground as its centrepiece.

Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, the director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, the curatorial statement points out the effects of colonial power in hardening 'differences across ethnic, religious, linguistic, and national affiliations' and states an aim to foreground 'new relations with Central Asian, West Asian, and African contexts.'

At Tollinton Market, these intentions unfolded within a British-era building off the Mall Road where six artists and collectives were presented in the best curated set of works of the biennial. Ottomans were positioned around a fountain on entering the building, with banners hung above that read, for example, Beware the Anti-Imperialist Imperialist, and Death without Death, Youth without Youth, Age without Age—part of the series 'Friendship of Nations' (2011) by Slavs and Tatars. Hassan Hajjaj's site-specific installation Le Salon (2020) similarly provided space to sit, with hundreds of plastic Coca-Cola crates refurbished into cushioned seats with bright rose-patterned yellow cloth common in Lahore's markets, dispersed across the building's perimeter.

The legacies of empire resonated throughout this grouping at Tollinton Market. Drawn directly on the walls within the arches of the market were large charcoal depictions of black men from the colonies who fought in the First World War on the side of the British. Titled Alchemy (2020) by Barbara Walker, this site-specific intervention left the charcoal unfixed and thus open to fading: perhaps a resistance to the work's possible commodification, and a humble and humane act that reflects on the transience of individual lives and collective memories.

John Akomfrah's video work, Expeditions 1: Signs of Empire (1983), uses a montage of images from the colonial period, along with extracts and speeches attributed to British colonial powers, to rehearse a common thesis in contemporary postcolonial theory: that empire was racialised and brutal.

Hoda Afshar offered a more expansive study of colonial violence in the two-channel film Remain (2018), which combines interviews with refugees on Manus Island, part of Manus Province in northern Papua New Guinea, which has been used to house refugees by the Australian government since 2013. Afshar juxtaposes vivid cinematography of the landscape with testimonies from refugees detained on this visually beautiful island. Subjects include a Kurd and a Sri Lankan Tamil—both are stateless and bear the legacies of postcolonial state violence in their countries—who talk about their friends who were killed back home, and the lack of medical treatment and food in their current location.

Remain demonstrates which bodies can move and which cannot, and in the context of the Lahore Biennale problematises that fact given how many in the art world have the privilege to seamlessly travel the globe, unlike a Baloch in Pakistan, for instance. The racialisation of the contemporary world is not just that of the old empire, Afshar reminds us.

This reality was indirectly highlighted at the Punjab University old campus, a red brick building built in 1882 by the British, where one large hall contained over 17 works, including Nedko Solakov's A Life (Black & White) (1998–ongoing), originally shown at the 49th Venice Biennale (10 June–4 November 2001). This time, two Pakistani workers painted two parallel walls measuring about 30-by-8 feet black and then white then black then white, over and over again: apparently the painters worked from 10am to 5pm for up to 3000 rupees per day—19.41 US dollars—with a half-hour break for lunch. The work seemed alienating and depressing for viewers. On my visit, one student asked, 'what is the point of this?' While another noted that the paint could be used to paint real walls around the city.

Of course, if you could get over seeing two grown men performing at low wages for an absent European artist, then some interesting works lay ahead. Of particular note were simple watercolour portraits of Pakistani Muslim men positioned against pastel backgrounds by Ali Kazim, which radiate with delicacy and affection—the artist neither exaggerates nor overburdens his subjects in symbolism.

The figures who populate Saeed's paintings mirror those that he has encountered at melas (wrestling festivals) and practices of pehlwans (wrestlers). The dramas that play out on the canvas, however, are universal...

A similar intimacy with the subject could be found in Saule Suleimenova's series 'Residual Memory' (2019), which uses plastic bags on polyethylene film to depict moments in the history of Kazakhstan that have been 'hidden' and written out of history books, such as the forced migration into Kazakhstan of people from across the Soviet Union; and acts of resistance, such as the youth riots of 1986. Immigrants in 1930s, for example, shows people who had been forcefully migrated to the steppes of Kazakhstan, depicted either cultivating or scavenging while guards in grey uniform supervise them.

Eight canvases by Anwar Saeed were displayed at his alma mater, the National College of Arts (NCA), from where he graduated in 1978 and where he taught for almost 30 years. For decades, Saeed has walked the Mall Road to NCA and back to his house near the River Ravi and the 'old city' of Lahore, and his paintings echo the landscapes he has moved through.

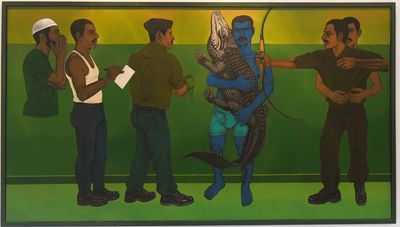

The figures who populate his paintings mirror those that he has encountered at melas (wrestling festivals) and practices of pehlwans (wrestlers). The dramas that play out on the canvas, however, are universal—they have more in common with Georges Bataille than the Victorian mores of Pakistani society. Radiant hues of dark and light blues, greens, and yellows emanate from large canvases depicting celestial dramas: scenes of love, violence, and death in different forms and degrees. In the 5-by-9-foot canvas, A Casual State of Being in a Soul Hunting Haven (2017), for example, various shades of green—green is read as the colour of Islamic piety in Pakistan—frame six men interrogating a central figure coloured in blue holding a large, almost phallic crocodile.

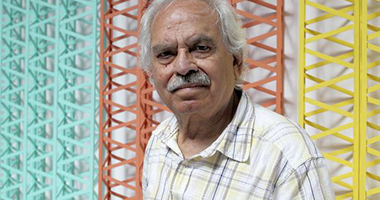

Saeed is a master artist and intellectual of Lahore, and it is no surprise that he received the lifetime achievement award from the Lahore Biennale. Six works by another master, Rasheed Araeen, occupied the next room at the NCA. Hung to the back of the room on a white wall were five works of collage of mixed media on board, which form part of Araeen's political work on race produced in the 1970s. These include How Could One Paint a Self Portrait! (1978–1979)—a self-portrait rendered in large strokes of black paint, over which the Nazi swastika and words 'Paki Go Home' and 'Blacks Out' are spray-painted in graffiti-style, with letters of rejection from various exhibitions pasted to its surface.

At the centre of the space at PIA Planetarium were blood-orange cubes that once formed part of Shamiyaana—Food for Thought: Thought for Change (2016–2017), first presented in Athens during documenta 14 (10 June–17 September 2017) as part of a set (shamiyaana, in Urdu) in which people were served food in a tent. In Lahore there was no food or tent, just the hollowed out sculptural cubes. I'm guessing they were to be moved by the audience, per his Zero to Infinity project (1968/2007), yet people seemed too intimidated to touch the cubes let alone move them, and they remained where they were: a point that seems to touch on the disconnect that could be felt at times between the ambitious global purview of the exhibition and its uneven connection with its context.

Indeed, while the Biennale successfully engaged Lahore with wider regional geographies, its conversation felt somewhat linear, with works referencing or representing other contexts ostensibly given to the city to view and learn from. Many were concerned with colonial legacies and racialised societies in general, but few confronted the oppressions (caste, class, and gender) within the context of Pakistan itself.

At the Punjab Institute of Language, Art and Culture (PILAC) in the surroundings of Gaddafi Stadium, screens and audio headphones were placed within fictional control rooms of a hydroelectric power station as part of Indus Water Machines (2020) by the Pak Khawateen Painting Club (Saba Khan, Amna Hashmi, Malika Abbas, Natasha Malik, Emaan Shaikh, and Saulat Ajmal). The work charts the use of Indus River water for British canal colonisation and later the harnessing of hydropower by the postcolonial state for development. One video showed a small protest in the highlands of Pakistan where dams are built; issues around water and its use are central to the political demands of Pakistani groupings including the Sindhi, Baloch, and people of Gilgit Baltistan. The video failed, however, to note the complicity of Lahori and Punjabi elites in extracting the majority of the water and power from the country's dams.

With that in mind, Lahore-based artist Imran Ahmad Khan's Temple (2019), a Biennale commission exhibited in the entrance of the PILAC building, offered a generative frame through which to consider the Biennale's relational frame, in which histories are absorbed to create future-facing projections connected to the past. Blocks of sandstone forming a roughly 16-foot-high stupa recalled an architectural temple, around which hundreds of clay figures and pots were positioned. Khan has spent the last few years learning the art of making these figures from clay potters, their forms based on the centuries-old clay figures of the Indus Valley civilisation, which Khan has imaginatively reworked.

Aesthetically arresting, Temple opened up the possibility of moving beyond the colonial legacies that loomed large in this edition of the Biennale by recovering and reworking local forms of visual culture to generate local effects. While connecting back to the Biennale's cultural sites and their associations with racial and hierarchical power—namely, the Mughal Fort, the British-era buildings along the Mall Road, and the state-built Gaddafi Stadium—Temple crucially presented its figures, in keeping with the Indus Valley civilisation they reference, in non-hierarchical relation. Not only a reminder of the past, but an invocation of a possible future. —[O]