This exhibition took place when the gallery was previously known as Choi & Lager.

'It ain't what you do', runs Sy Oliver and Trummy Young's 1930's standard, 'it's the way that you do it. And that's what gets results'. Daniel Crews-Chubb is a figurative painter, but there's no doubt that he owes his burgeoning success primarily to how he works, not to what he depicts. That's not so easy to analyse. 'It's like trying to define jazz', he suggests, 'when jazz just is'. But maybe we can take a look around and see whether, given time, we can get a feel for the jazz of Crews-Chubb's art.

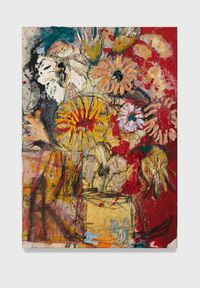

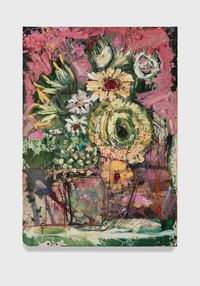

His characteristic approach is two-fold. First, as he puts it, simply enough –'I chuck a lot of stuff at the canvas'. That is to say oil paint, ink, pastel, spray paint, charcoal and plenty of rough pumice gel, which has a gritty cement-like texture. All is used without hierarchy, so the charcoal lines are as likely to be on top as the impasto oil, and the ink may be flung on late as well as being used to stain the fabric. He rarely uses a brush: application is by drawing, throwing, squeezing from the tube or smearing by hand.

Second, he adds extra swatches of canvas as he goes along, so that a visibly layered collage results, breaking up the surface and incorporating variable degrees of finish–including patches of raw canvas which act as 'breathing spaces' in the generally frenetic activity. Crews-Chubb discovered that this was 'a nice way to edit quickly–to cover over any section not working'. And it makes us more aware of the painting as an object, rather than image, an effect enhanced by how some pieces of fabric wrap around the edges. It's an intuitive, unruly process. Crews-Chubb works rapidly, ad hoc, on the floor or the wall as suits, taking chances, changing his mind, experimenting, enjoying the juxtapositions of thick impasto, raw material and scratchy lines. And he works across multiple canvases at once–making this series was 'like cooking for a dinner party of nine'.

The resulting works, then, resembles sculpture in the build-up of impastoed oil and pumice gel; drawing in the linear charcoal; collage in the patchwork effect. You might say they aren't paintings at all–except that, bringing those elements together, they do speak the language of painting. What matters most to Crews-Chubb are the abstract qualities he finds. They're not conventionally beautiful. 'There's just this shit everywhere', he says 'rips and tears, bits stuck on and crumbly surfaces'. Yet they do take on an aesthetic of their own, which you might call beauty by another means. His jazz.

All the same, Crews-Chubb is not an abstract painter. Why not? 'I wouldn't know where to make the marks', he says, 'if I didn't have a starting point.' In a way, his choice of beginnings amounts to more of the same 'chucking stuff on'–but the stuff is art history. Crews-Chubb's subjects are plucked from the classic, often somewhat romantic, traditional archetypes: heads, nudes, couples, the forest, group scenes... His muse, you might say, is the visual history of civilisation: from cave paintings to ancient artefacts to renaissance sculpture to modern masters. Actually, the art history isn't only in the subjects: his techniques are an amalgam of, say, de Kooning's spontaneity, Dubuffet's earthy textures, Auerbach's constant re-visions, Basquiat's fusion of graffiti and painting, Baselitz's undermining of figuration, Bram Bogart's weight of paint–and Rose Wiley's stuck-on extras...

If that sounds unoriginal, Crews-Chubb doesn't mind. He's a visual magpie who accepts that 'art informs art'–he sees artists as 'passing the torch' of the most favoured subjects in the same way as a fable might be retold down the ages. Crews-Chubb is no symbolist, though. It's the look, not the meaning, which appeals to him. No existential meaning is intended. He sees his motifs as conduits towards mark making.

Yet broader interpretations of his practice are possible. As Barthes had it, the work escapes the author. You could, speculatively, read a critique of image saturation into Crews-Chubb's approach: his mining of the past is the equivalent of surfing the Internet; we live in post-modernity with access to every image ever made at the touch of a button; it's too much, the motifs are dulled by repetition and the limitations of the screen. That would be a reason for making appreciation of the work depend on seeing it for real. 'In a way', says Crews-Chubb, 'I'm a reactionary—my surfaces are a reaction against the flatness of a digital image'–and he takes the risk, thereby, that people will devalue the work by judging it from the very digital images they seek to evade.

This show deals with flowers specifically. What does the particular subject bring? They're all from Crews-Chubb's head, not derived from particular flowers or paintings, but they still trail art history behind them: the Dutch golden age, Manet, Monet, Fantin-Latour, Van Gogh, O'Keeffe, Warhol, Katz, Twombly, Murakami ... The floral torch burns brightly. More particularly, flowers bring clarity and paradox. Clarity in that we quickly grasp what we're looking at: we know where we are with flowers, compared with, say, a tangle of figures that deals the viewer an immediate challenge to sort out what's going on. 'Flowers', says Crews-Chubb, provide 'a nice way of judging my application through a motif which is clear'. There's paradox too. Our default expectation of flowers is colour, beauty, comfort. And what we get is messy, scrappy, in your face, aggressive. It's the ideal subject to foreground Crews-Chubb's aesthetic contrarianism. He says: 'I asked myself, why paint flowers now? They're such a conventional and pretty subject. And then it seemed ballsy to do just that.'

Again, I'm tempted to run a speculative narrative. We've had centuries of beautiful flowers, so much so that we've become tired of them. There's nothing new left, all we can do is corrupt the past into a dirty secondary form. And flowers often act as a Vanitas. We will die, they remind us, just as the more visibly fleeting flowers will die. These are flower paintings for the end of times.

It turns out, then, that flowers are an ideal subject to trigger Crews-Chubb's experiments in the laboratory of his art–but it's still the language that matters. The surface outweighs the image. And either you'll like his highly distinctive language or you won't–it's largely an intuitive matter, fitting in with how the paintings are produced. But you do need to give yourself time in their physical presence. And it turns out that there's quite a lot you can think about while you're spending that time with these paintings, letting the language soak in, getting in tune with Crews-Chubb's jazz...

Press release courtesy JARILAGER Gallery.

12 Eonju-ro 165-gil

Gangnam-gu

Seoul

South Korea

https://www.jarilagergallery.com/

+ 82 (0)10 8191 5834

Wednesday–Saturday

1pm–6pm

and by appointment