Juliana Engberg Catalogues Catastrophes at Auckland Art Gallery

Pandemic misery finds company in artworks responding to the Fukushima disaster, the Christchurch earthquake, and other calamities.

Pierre Huyghe, (Untitled) Human Mask (2014). Single-channel video. Copyright Pierre Huyghe / Societe Des Auteurs Dan Les Arts Graphiques Et Plastiques. Copyright Agency, 2021. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Anna Lena Films.

New Zealand art critic Anthony Byrt described Juliana Engberg as 'one of the most important curators ever to have come out of the Southern Hemisphere' when she joined Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in February 2020. When the pandemic struck, she extended her seven-month contract with the gallery through the end of 2021.

Engberg, who directed the Biennale of Sydney in 2014 and curated Australia's presentation at the Venice Biennale in 2019, spent much of the past year piecing together All That Was Solid Melts, a transhistorical exhibition about isolation, grief, and people's efforts to regather their strength in the wake of a disaster.

The resulting show feels both universal and personal. On an exhibition walkthrough, she told Ocula Magazine, 'I did lose a lot of people actually, not necessarily through Covid, although a couple of them. Some as a consequence of Covid—suicide—and other people who just died and I couldn't be with them.'

'I've made a show I hope is quite repairing and cathartic for people—it does get quite joyful as we go along,' she said. 'Let's keep moving.'

None of the artworks in the exhibition, which include loans as well as pieces from the gallery's permanent collection, were made in response to Covid-19. Nevertheless, several seem even more pertinent to our current predicament than the events that inspired them.

Pierre Huyghe's compelling video (Untitled) Human Mask (2014), for instance, was made in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. We see a solitary figure—ostensibly a young girl—playing with her hair, gazing out the window, and tapping her... paw. She rises suddenly in search of something, hesitates, and goes back as if she has forgotten what she was doing. On closer inspection, we see she is not a girl but a monkey—a macaque in a dress and an inscrutable human mask—left behind after the area was evacuated. Huyghe couldn't have known, but it seems obvious now that the monkey is us under lockdown.

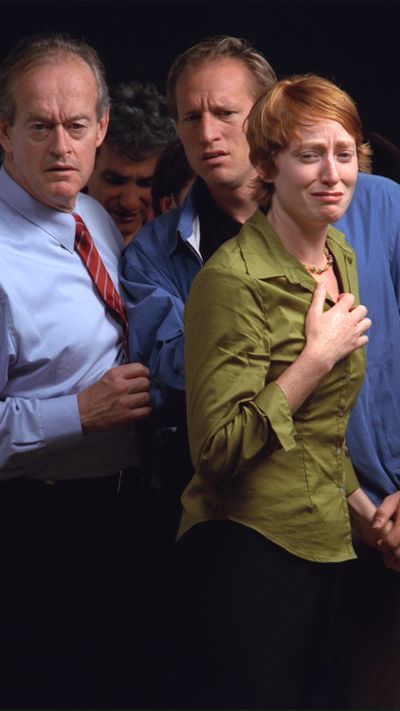

Then there's Bill Viola's Observance (2002), a video of an audience responding in distress to something unseen. The work was made shortly after 9/11, but takes on new meaning in light of the pandemic, a diffuse disaster with none of the slow-motion televised spectacle of the terror attack.

'We're looking at this hollow space, this unspecified anxiety, this unknowable, unnameable thing,' Engberg said.

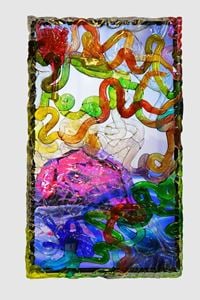

Julia Morison's wall-mounted Liqueurfactions I–IX (2011) are concrete-like rectangles created from the spirits that spilled from smashed bottles of alcohol—crème de menthe, amaretto, sambuca, and so on—and the grey goo that seeped out of the ground after the Christchurch earthquake. In the context of All That Was Solid Melts, they speak to the grim sameness of days under lockdown, and the heavy drinking it prompted in many.

Coping strategies are also explored in Douglas Gordon's Private Passions (2011), a photograph of a candle-gripping hand splashed with ejaculations of burning hot wax. After spending so much time alone and in pain, both spiritual beliefs and carnal pleasures are weighed up as engines of survival.

Other works depict volcanoes erupting, buildings razed to rubble by earthquakes, and war. There are also pieces whose very inclusion speaks to loss, such as those by Australian artists Kate Daw and John Nixon, both of whom passed away in 2020.

In the latter part of the exhibition, Engberg looks for silver linings. During the pandemic, birds returned to urban environments, where their songs reverted to a lower, less shrill tone not heard since the 1950s. She marked the phenomenon with the inclusion of taxidermy native birds borrowed from the Auckland Museum.

The exhibition ends with Pipilotti Rist's Extremities (smooth, smooth) (1999), a video installation that feels more like a guided meditation. Against a backdrop of stars, Rist allows us to turn our attention towards disembodied parts of our anatomy—a mouth, an ear, a foot—unburdened by our conceptions of ourselves in disrupted personal timelines, dispossessed in different ways by a global plague.

It's a welcome respite, but after leaving the exhibition another work bubbles back to mind, like the ooze Julia Morison collected in Christchurch.

Melbourne artist Callum Morton's Cover Up #34 (2021) is a work sculpted from ureol—a product typically used to make industrial prototypes and moulds—to resemble a framed picture covered with a drip cloth. What has been covered up and why are left to the viewer to hypothesise. Could it be the origins of the pandemic? The inequality of its impacts and our efforts to ameliorate them? Or our feelings about the whole damn thing, concealed even to ourselves?

'It's a very good example of the strategies of minimalism,' Engberg says, which was 'always about covering over, tidying up, making very serene and classical that which is unruly, chaotic and messy.'

'It was trying to control things, but now [in Morton's work] it's become wrinkly. We've gone through too much,' she said.

All That Was Solid Melts continues until 10 October. —[O]