Afterimage: Dangdai Yishu at Lisson Gallery, London

An afterimage is a false visual burned onto the eyes even after its source is no longer being viewed. Victor Wang, the curator of Afterimage: Dangdai Yishu (3 July–7 September 2019) at Lisson Gallery, London, borrows the term to describe one of the key accomplishments of contemporary art: the accommodation of work that is post-figurative, or 'after image'. But the exhibition, which includes work by nine Chinese artists across generations, is also an afterimage in the former sense—a lingering view of a past that has in some ways outstayed its welcome.

Wang Youshen, Newspaper / advertising (1993). Exhibition view: Afterimage: Dandai Yishu, Lisson Gallery, Lisson Street, London (3 July–7 September 2019). Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

The exhibition is spread across two spaces, beginning at 27 Bell Street and continuing a short walk up the road at 67 Lisson Street. The first piece viewers are likely to encounter is Whole Dark (2005), a cartoonish fibreglass sculpture by Beijing artist Xiang Jing. Wearing lace-up leather shoes and a traditional collarless shirt, this androgynous figure seems representative of transition, neither East nor West, past nor present.

Continuing inside, the space opens up to Protruding Patterns (2014), a large installation by Lin Tianmiao, who was born in 1961 and was part of China's first wave of contemporary artists. Sitting on patterned red rugs that cover the floor are fluffy, pom-pom-like words in lipstick hues. Written in English and Chinese, these are largely terms used to describe or diminish women, including 'Sea Donkey' and 'AV女优' (porn star). While Lin denies being a feminist, dismissing the term as Western, the work nevertheless draws attention to women's sliding position in Chinese society. In the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report, China fell from 57th place in 2008 to 103rd in 2018.

Works by Ma Qiusha, born in 1982, are likewise imbued with gender politics. Wonderland — Shaping Flesh (2016) looks like stone masonry, but on closer inspection reveals itself to be made up of nylon stockings in nude hues, clothes worn to conceal and protect female bodies. Ladders in the ostensibly solid 'stone', which the artist repaired with clear nail polish, suggest vulnerability. The neighbouring work, Page 21 (2017–2018), is a cyanotype on paper of a pornographic photo—a blue image of a blue image—whose nakedness was scratched out as the image was developed, leaving a white void. The artist says this whiting out of the model's erogenous zones was motivated by composition, not moralism, as she attempted to accept the female body as pure art-making material, just as she treats her own body in performances.

Censorship is, however, unequivocally the subject of a work by new media artist aaajiao, also born in the 1980s. 404 (2017) is comprised of two ink-sponge rollers with which audiences are encouraged to paint the walls of the gallery. Each rotation of the rollers creates a '404' print, and the walls in this section of the gallery are now densely covered with the image. The work gives a palpable sense of the omnipresence of China's Great Fire Wall, which polices even visitors to London travelling with Chinese SIM cards.

Windows by aaajiao's work look out onto a courtyard littered with broken bricks, the result of a four-hour performance by Li Binyuan, Breakdown (2019), for which the artist painstakingly demolished a column of bricks. Video documentation of the performance is embedded in the bookshelves holding the gallery's publications. The work very much speaks to a tradition in China that took off before the artist's time—in the 1980s and 90s, when artists such as Zhang Huan used performance both to illustrate their abjection and circumvent censorship.

Downstairs, the video Untitled, Xinjiang (2018) by Zhao Zhao is perhaps the most intriguing inclusion in what is mostly a sampler of familiar and established artists. A graduate of the Xinjiang Institute of Arts, Zhao shoots video portraits of what appear to be Uighur people, one of China's ethnic Muslim minorities, in Xinjiang. A woman and her son, for instance, stand in front of bunches of grapes drying on a clothesline. The child, who looks to be about four years old, is unable to stand still for the portrait, and instead fiddles with a bubble wand whose detergent is spent. He sticks the thing in his mouth, then holds it like a gun and stares down the barrel. His mum, in a green cardigan and floral print dress, looks exhausted.

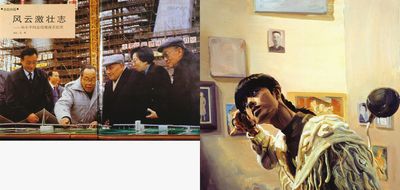

That the portraits in Untitled, Xinjiang feature only women and children prompts the question: where are the men? The Pentagon estimates between one and three million Muslims (largely men of working age) are currently being held in Xinjiang detention camps. The two works in the gallery's 67 Lisson Street space—a room papered with newspapers from 1993 by Wang Youshen and a video installation on the nature of perception and reality by the youngest artist in the show, post-90s Shen Xin—are more elaborate; but it is Zhao who best captures China's stymied progress, the afterimage of authoritarianism still burning decades into the country's 'economic miracle'.

Witness to Growth (1999–ongoing), a series of acrylic on canvas paintings by Yu Hong displayed back in the Bell Street space, further subverts the celebration of state successes at a time when individual liberties are being lost. Yu juxtaposes paintings of modest moments in her life with blown-up newspaper photos of events in China that took place in the same year. The small accomplishments of an individual life—the artist cutting her bangs in a mirror, a baby arriving home in a stroller—are given more wall space than the staging of political rallies and the construction of bridges. These are figurative paintings, rendered in a social-realist style shared by Yu's husband Liu Xiaodong, one of two Chinese artists represented by the gallery (the other being Ai Weiwei). It's figurative work, image not 'after image', but definitely an afterimage still burning on the retinas as Yu tries to process China's progress, which has been both dizzyingly fast and depressingly slow.

As a whole, Afterimage: Dangdai Yishu is courageous if somewhat broad. Including artists of such different generations working in different media with such different sensibilities seems like throat-clearing. Offering a primer in Chinese contemporary art is understandable given London audiences aren't necessarily steeped in what Chinese artists are doing. But with Lisson having opened a gallery in Shanghai this year, future shows about Chinese contemporary art will hopefully have a little more to say. —[O]