John Henderson Paints an Atmosphere of Conditions

Perrotin | Sponsored Content

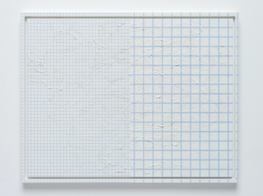

John Henderson. Courtesy the artist.

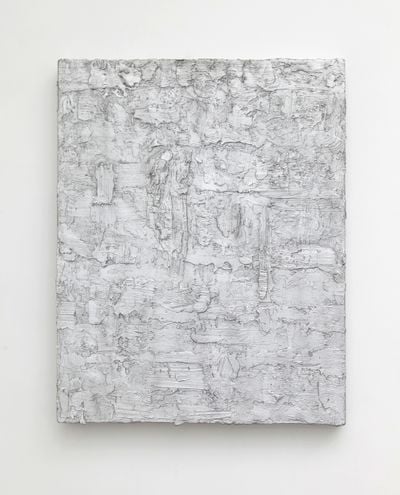

John Henderson. Courtesy the artist.

For over a decade, Chicago-based artist John Henderson has been transmuting chemicals, metals, frames, and forms into subtle lines of inquiry that engage directly with the history of modern Western painting.

In his series 'Proof (wall rip, verso)' (2014), for instance, the artist took a swatch of linen and glued it to the wall, ripping it once it had dried to reveal layers of paint and plasterboard. He then scanned the fragment, enlarged it, and printed it via dye sublimation before it was applied to an aluminium frame.

The works are 'paintings in both intention and extension', explains Andrew Blackley in his essay for the catalogue produced on the occasion of Henderson's solo exhibition Model at Perrotin, New York (25 April–8 June 2019).

Though paint itself may be absent, the work's various components—from the action of pulling the swatch from the wall, the enlarged view of the otherwise overlooked weave of the linen, the act of stretching the image across the frame, and the seepage of dye into the surface of the print—all gesture towards the process of painting itself.

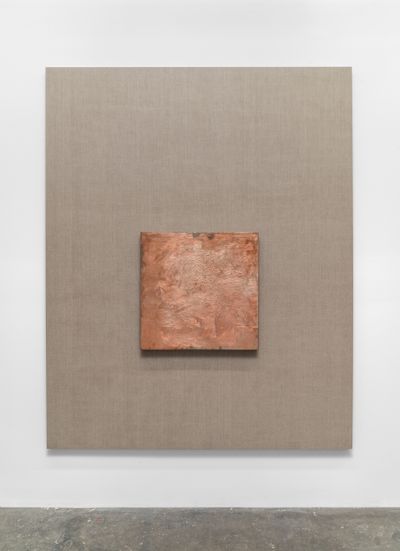

Henderson has explored another indirect approach in his 'Cast' series (2010–ongoing), whereby paintings are cast in bronze or aluminium, deflecting original paintings into tactile surfaces that hover between objects, artworks, and sculptures.

There is a 'promiscuity' in the interplay between these lines of inquiry, Henderson explains, which are occasionally supplemented with short video works.

The early video Cleanings (2010), for instance, produced two years after the artist graduated from Northwestern University, captures the artist mopping the floor of an empty room, rendering it darker with each stroke of water. It is a process that is both additive and impermanent, the artist explains, engaging with the gestural abstraction of Jackson Pollock and the studio as a site of performance.

More recent videos, including Untitled (2014) shown at Proyectos Monclava (Far or hid, 21 September–27 October 2018) remove the artist as central presence. Instead, we witness the water of a rainstorm thrashing against the skylight of the artist's studio, which he films from below.

In advance of his solo exhibition The Return at Perrotin in Paris (4 September–9 October 2021), the artist discusses how the past year has further embedded such approaches to self-reflexivity, as well as the concerns that thread through his broader practice.

TMI wanted to begin with the self-reflexivity of your methodology, and how this has played out during the cycles of lockdowns over the past year. Has it led you to new inquiries?

JHA self-reflexive impulse has always been at the core of the work—a kind of self-consciousness where I am watching over my own shoulder, both monitoring and pre-empting the actual art-making and other physical activities of the studio.

I don't know if I would call it a conceptual framework, per se. It's more an attitude that I foster, like a premature or anticipatory correction. An embrace of the anxiety of production.

A coding happens through this kind of attitude that is reflected in the artworks. It is there from the very beginning. I operate knowing in advance that the physical, rather traditional engagement with materials in the studio will be fed through processes that flatten, replicate, or reproduce the painterly gesture.

I operate knowing in advance that the physical, rather traditional engagement with materials in the studio will be fed through processes that flatten, replicate, or reproduce the painterly gesture.

Before the pandemic, I was already immersed in the studio alone, and that kind of solitude supports and promotes this kind of self-conscious analysis.

The last year has been an intensification of that, rather than something that has wholly changed my working methodology. More like an oven that has cooked that sensibility and added a kind of acceleration and density—a compression—to something that was already going on.

TMWas that a welcomed acceleration?

JHIt's not that it was positive or negative, but it feels like an honest reflection of the world inside and outside the studio. Something in the work feels like it has begun to render the current atmosphere.

TMYou have these lines of inquiry—such as the 'Types' and the 'Casts'—and in each series there is a negotiation happening, which results in the transmutation of forms and images. Within the breaks between series, how do you experiment to move towards a new line of inquiry?

JHI don't plan on starting a new series, it just happens. I don't think about it in terms of fighting redundancy. I think about it in terms of fleshing out or exploring different corners of a room. There are different considerations and attenuations across and between the series but also a shared, overarching conversation.

There is a through line across all of the works, a cohesion, but also simultaneously there's something kind of promiscuous about the interplay between the different inquiries and mediums.

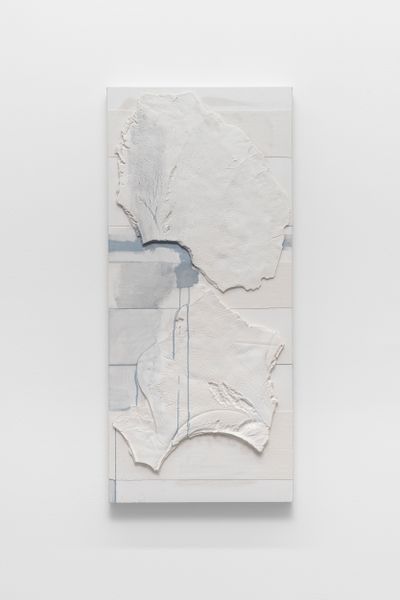

I have been thinking about the relationship between photography and casting, specifically for the upcoming show, but also photography and my approach to painting.

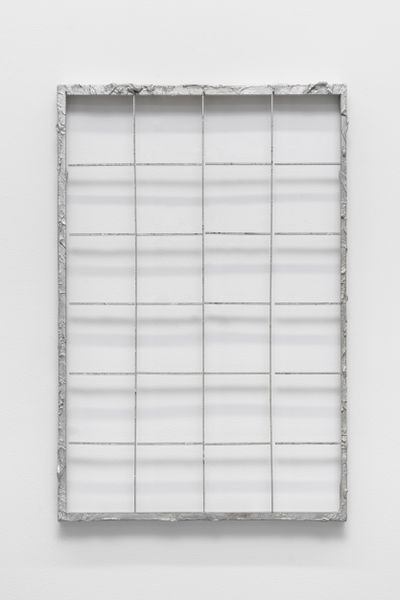

I consider casting to be fundamentally photographic. There is something intensely technical about the photographic process—the capturing and developing of an image—that rhymes with a process like electrotyping: imprinting the painting's topography into a mould and transmuting that surface into a new copper object. The dislocation of an image from its original source.

There is also an implication of loss in both the photographic and casting process. The final image represents something that is no longer there. More recently, I've been treating casts as incomplete. Not deficient but still in motion; still open. Like blank canvases already populated with information.

For the upcoming show in Paris, I've repainted many of the casts, while others have been cut apart and reassembled with different materials. I'm not thinking about reanimation but rather a continuation of that self-reflexiveness we were talking about. I'm making loops—paintings to casts and back again.

TMYour practice engages with modern Western art history, and in particular, Abstract Expressionism. In works by painters such as Jackson Pollock, there is this ecstatic moment of completion that is built into their legacy. I was curious about that moment of arrival in your own work. Is it through the object itself, or is it through the process of translation?

JHFor me, the question is: where is the location? Where is the actual expression located? It's hard to track. If there is something anticipatory that I build into the work, how does this code or change my approach to the original object?

There is a moment of realisation in the meditative gaze that is not exclusive to looking at art. It also happens in life outside of the studio or gallery, of course.

When does the work become complete? When is the expression? Where is the expression? It is located in the art object shown in the gallery? Or is it in the studio in the source object that I kept for myself or destroyed? I think it's happening at both and times places simultaneously. Or is it located somewhere in the middle of the process?

TMYour video piece Cleanings is frequently positioned as a starting point to understanding your methodology. It is a very simple and impactful video.

JHYes, that video can be used as a key or filter, using it as a lens to look at newer works. I consider it to be my first work. I made it on a whim.

I suddenly had the idea and shot it right away on consecutive days. I can talk about Cleanings now in terms of self-reflexivity and self-consciousness, but at that time, there was a freedom to just having an idea and letting go.

That video presents a narrative that is both additive and subtractive. There are four separate performances during which I mop the unsealed floor with water. After each iteration, the floor is left to completely dry out, erasing my mop strokes. The impermanence signalled by that reset underscores the performative mentality of the rest of my practice.

TMDo your videos provide cornerstones to different periods of your practice? In Untitled (2014), the video you showed as part of For or hid at Proyectos Monclova, you are no longer visible in the video—all we see is water thrashing against a skylight in your studio.

What does that signify to you in terms of your work's expansion, not having your presence there, but those of natural forces instead?

JHI don't really think about the videos as marking time or bracketing certain periods of work. The videos are occasional. I don't make them regularly. I don't force them out.

They are hiccups that are always straightforward in their ideas and production. They feel divergent from the rest of the work where I am, through various activities, squeezing or moulding or struggling the image into the world. In the case of the skylight video, the title being Untitled signifies an inclusive blankness.

My old studio had these beautiful skylights that were pretty decrepit and leaked. During a rainstorm, I placed the camera on the floor and recorded the rainfall through the skylight. The metal frame of the skylight instantly became a painterly set-up, looking like the wooden stretcher bars of a canvas.

The rainfall—similarly to the water from the original Cleanings video—became a stand-in for paint, but the person and tool articulating the expression are absent. My absence signifies a first-person perspective. It signifies the act of looking. In this video, my position is the same as a viewer's. A simultaneously passive and active reception of the world. Looking slowly.

There is a moment of realisation in the meditative gaze that is not exclusive to looking at art. It also happens in life outside of the studio or gallery, of course.

TMThe tension in your works results from an artful negotiation between hyper-specificity and expansiveness, and the ability to reference other media and the world outside.

I am curious about their relation to the built environment, and the architectural aspects of the frame and the canvas and the materials you use, like brass or copper, that absorb the fragile human or organic trace.

JHIf you were to break down my paintings on canvas into their constituent parts, you are left with a bunch of humble materials. Assembled together, they remain fragile despite our grand narratives around painting. They are subject to damage quite easily.

There is something that feels provisional in an object that can be stretched and un-stretched, rolled or folded.

Perhaps this is forced, but there's an analogy with architecture, especially in the United States, where houses are made with relatively humble materials: wood studs, plywood, drywall. Yet, when combined, they create these impressive architectural situations that exceed the sum of their parts. Their completeness or fixedness, however, is usually often just perception.

The chromatic identity of the original object is somehow absent in the cast, while the surface of this new version of painting is still moving.

I think about architecture as situated in the world at large and subject to decay and ruin like everything else. Even in the built environment, the trajectory is not linear.

Things do not go on forever. You have to be there to maintain them. Eventually, it all deteriorates, collapses, and needs to be rebuilt. Things change. Things loop.

In reproducing a painting through casting or electrotyping, there is a repetition that feels like an insistence of the original image. There is a re-enforcement by translating it into materials that are relatively permanent, like bronze or copper, which have this connotation of longevity.

Even if the material of sculpture is strong and long-lasting, it does not feel fixed to me. These things can still feel very much in process. I'm starting to realise this more and more. Even images or objects that are flattened or compressed can continue to grow in new directions.

For instance, the electrotypes—the copper pieces—could be buffed into even monochromatic surfaces. Like copper pennies. Their negative mould is coated with silver to make it electrically conductive.

Traces of this silver transfer unpredictably into the copper surfaces during the electro-chemical process. Of course, I could remove these from the final surface but I choose to leave the chance compositions that the silver deposits create.

It's a way to signify that even if the physical image of the painting is now locked into an impervious material, the image can be in flux. It can retain a painterly sensibility, an embrace of chance and contingency.

The sculptural surrogate, or replica, is re-painting itself. The chromatic identity of the original object is somehow absent in the cast, while the surface of this new version of painting is still moving.

TMIt's an alchemic process, isn't it? Turning one thing into another. I really like the word 'squeezing' that you used, to refer to the process of squeezing an image in the world. Because often your practice involves the processes of removal or erasure, but it is also just as much about squeezing.

JHThere's something that isn't straightforward in terms of making paintings now. The process of making anything feels difficult psychologically. Squeezing, or having some kind of struggle. There is a kind of unseen resistance working against me that I feel as I am in the studio.

TMSqueezing does not necessarily have to be a forced thing. It also can be a fragile thing.

JHSqueezing can be a ringing out, a struggle, a purge; but also, to squeeze in can also be to sneak in. A risk. To do something without being sure of the results or the outcome. —[O]