Massimiliano Gioni and Daniel Birnbaum on Dream Machines

Left to right: Massimiliano Gioni, Daniel Birnbaum. Courtesy DESTE Foundation. Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou.

Left to right: Massimiliano Gioni, Daniel Birnbaum. Courtesy DESTE Foundation. Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou.

Perched on a seaside cliff by a winding road, just a stone's throw from Hydra's port, stands a former slaughterhouse. Since 2009, DESTE Foundation has transformed this small complex into a project space, drawing the art world's attention to the picturesque Greek island once a year each June.

For over a decade, the Slaughterhouse has showcased predominantly solo exhibitions by renowned artists such as Kiki Smith, Kara Walker, and Paul Chan. Last year, Jeff Koons presented a monumental exhibition, Apollo, featuring the kinetic sculpture Apollo Wind Spinner (2020–2022) towering above the building's rooftop.

This June, Koons, together with DESTE's founder Dakis Joannou and his wife Lietta, ceremoniously gifted the artwork to the island. Unlike Koons' widely criticised Bouquet of Tulips, a public sculpture unveiled in Paris in 2019, this gift was accepted without rousing concerns about disrupting the island's landscape or the stability of its holding platform.

Consequently, Koons' rotating, weathervane-like sculpture became the starting point of Dream Machines (20 June–30 October 2023), the latest exhibition at the Slaughterhouse co-curated by Daniel Birnbaum and Massimiliano Gioni.

The two curators have extensive careers behind them and strong established positions in the art world. Birnbaum served as the artistic director of Stockholm's Moderna Museet and rector of Städelschule in Frankfurt, and Gioni has been the artistic director of New York's New Museum for nearly a decade. Their curatorial experience spans countless exhibitions and biennials including the Venice Biennale, which was directed by Birnbaum in 2009 and Gioni in 2013.

Sharing a recurring fascination with the intersection of art and technology, with Dream Machines the two delved into the reciprocal influence between machinery and artistic imagination. The cleverly composed show features an impressive array of over 30 works within a minimal space full of contradictions.

Ambitious yet soft-spoken, their endeavour aims to encapsulate significant epistemological shifts that have unfolded over the past century in relation to technological developments. Shown alongside are works by artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Thomas Bayrle, Mire Lee, Mika Rottenberg, and Fischli and Weiss, in addition to reprinted instructional sketches and reconstructed copies of odd machines.

On the opening night, though versed in such events, the curators were sweating more than usual. Taking turns cycling on Maurizio Cattelan's Dynamo Secession (1997–2023), a bicycle transformed into an electricity generator, their exertions activated a hanging lamp that lit the exhibition space and the rudimentary arrangement of objects and screens within.

The second source of illumination in the room came from a reconstruction of Brion Gysin's Dreamachine (1961): a mesmerising kinetic machine favoured by Beat Generations such as William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg that employs a rotating turntable and flickering light in sync with the brain's alpha waves to induce a trance-like, ethereal state.

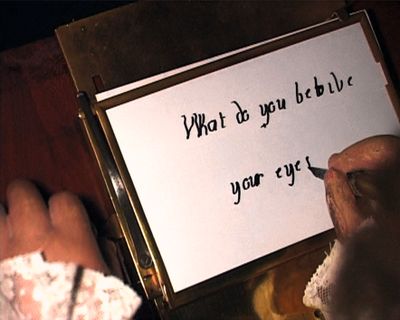

Amid the intermittent flickers introducing movement to the room, one catches glimpses of Philippe Parreno's The Writer (2007) playing on a small tablet featuring an eerie automaton writer, a collection of suspended metallic sculptures by the late American Outsider artist Emery Blagdon, and Pamela Rosenkranz's Healer (Waters) (2019), a serpent-like robotic machine manoeuvring across the exhibition floor.

Outside, another tablet plays a film by Jacqui Davies, compiling iconic film scenes, found footage, and images of the exhibited works into a video catalogue of the show. Above it, on a small balcony overlooking the Mediterranean, adjacent to a reconstruction of Doctor Wilhelm Reich's notorious Orgone Accumulator (1940)—a wooden box purported to cure various diseases, including cancer, which led to Reich's imprisonment for fraud—an inconspicuous QR code hangs on the wall.

The code directs viewers to a page by Acute Art, a production company for virtual and augmented reality (AR) that focuses primarily on blue-chip artists and is led by Birnbaum as its artistic director.

Through the browser-based AR, one can see Lee Bul's augmented piece and NFT Willing To Be Vulnerable – Metalized Balloon VER. AR22 (2022) floating gracefully above the water.

While visitors attempt to capture a screenshot of the floating airship, Judith Hopf's concrete sculpture Phone User 5 (2021–2022) stands quietly on the roof of a nearby compact building. As the title implies, the sculpture depicts a figure engrossed in their smartphone, mirroring the choreography of those observing the AR piece on the balcony above. Petrified in its stance, Hopf's figure embodies fears surrounding the impact of technology and colours the entire exhibition with a bleak undertone.

Dream Machines explores the all-too-human, Icarus-like yearning to transcend one's limitations, which in turn gives birth to both magical fantasies and terrible nightmares—or just odd instruments. The exhibition functions as a sort of miniature time capsule, offering a retrospective view of the past long century through a collection of out-of-date and at points broken machines.

On the occasion of the opening, Birnbaum and Gioni discuss this condensed exhibition with Frankfurt-based writer and curator Ben Livne Weitzman, ruminating on the utopian optimism and fearful paranoia that technology arouses.

BLWDream Machines is an extensive show about a massive topic in a tiny space at the periphery of an island seemingly untouched by the surges of technological progress. How did this contradictory exhibition come to be?

MGFrom the beginning, Dakis and Lietta Joannou's vision of transforming a former slaughterhouse near Hydra's port into a project space opted for repurposing a small existing structure rather than constructing a new one. A readymade, in a way.

While the space typically hosts annual solo exhibitions, exceptions were made for Dream Machines and a small group show I curated in 2021, titled The Greek Gift. This year, the Apollo Wind Spinner—the centrepiece of Jeff Koons' exhibition, Apollo—was gifted to Hydra and will remain permanently displayed, so we thought it would be interesting to use this work and the slaughterhouse itself, a killing machine, as a starting point for an exhibition.

I had invited Daniel to contribute an essay to the Koons exhibition catalogue and he drew very interesting connections between Koons' work and Duchamp's, which paved the way for this rather small philosophical show about machines.

The paradox of staging a show about such a complex theme in this remote location and with limited exhibition space is undeniably evident. However, perhaps like a butterfly effect, this humble origin has the potential to reach and impact a wide audience.

DBIn Apollo, Koons positioned his art in relation to the readymade. When I was asked to write the essay for the catalogue, I wanted to connect it to Duchamp's Coffee Mill (1911), which is often treated as the secret key to his other works.

In general, I think we are often formed by the places where we work. At the Moderna Museet where I spent almost a decade, one of the key threads running through the collection is art and technology. There is an extensive collection dedicated to Duchamp, filled with authorised replicas, and the museum is connected to Experiments in Art and Technology, an initiative that aimed to bridge the gap between artists and technologists.

Nowadays at Acute Art, we're driven by a similar vision. We want to see what happens when artists are given access to tools they wouldn't typically have.

We conducted a little experiment with Koons, which we showcased in Stockholm. Initially, we were focused on big names like Olafur Eliasson and Marina Abramović, but now we're more interested in working with up-and-coming artists.

BLWLocomotion seems to be a key element in the show, as well as reproduction. For example, you do not show Duchamp's original Coffee Mill, understandably, but Ulf Linde's replica of Duchamp's work.

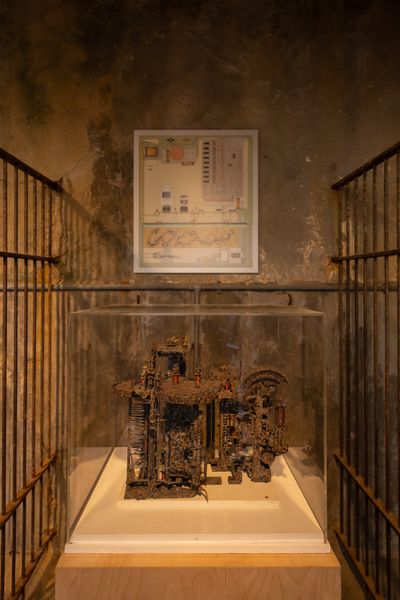

MGOf course, we simply would not be able to show the originals in the Slaughterhouse, which is a place with no climate control and some rooms are basically outdoors.

However, a show centred on machines is inevitably a show about reproduction, where the notion of an original loses its significance and copies take centre stage. That is why we have an actual Duchamp, and then Linde's copy and Elaine Sturtevant's replica.

The exhibition is also filled with artworks and objects—like Brion Gysin's Dreamachine or Wilhelm Reich's Orgone Accumulator—that are built from instructions one can find online or in old books. These pieces suggest that art, when freed from sentimental projections, can be easily built, and reconstructed using instructions like machines themselves. Duchamp explored this idea in his work, through his notes for The Green Box (1934), for example.

As the mysterious secret key to Duchamp's works, Coffee Mill was also an erotic metaphor. It's very sensual, which is one of the sub-themes in the show, relating to the Surrealist and Dadaist idea of the machine as carnal, as flesh.

In this sense, Duchamp's famous The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923), referred to also as The Large Glass, was also described by his author as a 'bachelor machine', a peculiar combination of sexuality and fatality—a machine that engages in self-pleasure but doesn't produce anything tangible.

This explains why many elements in our show are designed to rotate and move. They are caught in a kind of masturbatory mechanic ballet: they are unproductive machines.

DBAs compact and small as the show is, we began thinking about it as a show about a century of art and technology. Over this period, several paradigmatic shifts occurred with the advent of various technologies: photography, cinema, video cameras, television, the internet, and now emerging technologies like AR and VR, which you, Ben, and I are currently grappling with and trying to understand. These transformative changes are all present within the exhibition.

MGThis is also evident in the displays we have: a Barco monitor from the 1970s, an iPhone showing Pipilotti Rist's Selbstlos im Lavabad (Selfless in the Bath of Lava) (Bastard Version) (1994), and a VR headset for Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg's It Will End in Stars (2018).

BLWThe show does feel like an ode to a century driven by technological advancements.

MGYou can also think of it as a requiem, filled as it is with obsolescent machines. There is an undercurrent of fear and angst in the exhibition.

We present a diagram from an 1810 medical book depicting a case study of James Tilly Matthews, a London tea broker afflicted with schizophrenia and haunted by the paranoia of being controlled by an Air Loom—a fearsome machine that used mesmeric rays and enigmatic gases to manipulate minds from afar.

This fear of being dominated by a machine is the same as our contemporary unease surrounding the potential dominance of artificial intelligence in our lives.

This fear of being dominated by a machine is the same as our contemporary unease surrounding the potential dominance of artificial intelligence in our lives. It echoes the historical fear that the Luddites, members of a 19th-century textile workers movement in England, harboured towards the advancement of looms, as they believed this technology threatened their livelihoods.

BLWIn a way, it did. As did many of these machines. Their fear was not unjust.

MGThe title of the exhibition, inspired by Gysin's Dreamachine, tries to encompass this dual nature of technology. It expresses a utopian belief in its capacity to improve our lives, while acknowledging the thin line between a dream and nightmare.

DBThis is the show's key idea—technology brings forth both new possibilities and a duality of utopian optimism and fearful paranoia. The exhibition features a range of works, from established artists to peculiar machines, all embodying this double-edged nature. While the show explores new possibilities, it doesn't solely embrace a techno-optimistic perspective. Instead, it delves into how technology challenges the essence of art.

This happened with the emergence of the readymade, which is inherently linked to the appearance of photography. Each shift in technology opens new possibilities for what an artwork can be. Lee Bul's AR piece hints at the potential of the next shift towards mixed realities. It might not happen immediately, but it seems that these technologies will become omnipresent in our future lives.

Technology brings forth both new possibilities and a duality of utopian optimism and fearful paranoia.

BLWAnd yet, this exhibition is not really 'techy'. It has a mechanic, almost analogue vibe.

MGWe wanted the show to feel a bit rudimentary. In this context, Maurizio Cattelan's piece—with his bicycle powering a light bulb that lights the exhibition—undermines the idea of technology as triumphant.

The whole show feels a bit rickety, held together with tape and wire—it is more the work of a bricoleur than that of an engineer. We included many pieces that contrast the triumphant idea of technology as a promise of a future filled with new life-changing experiences.

I think the 'Healing Machines' (c. 1955–1986) by Emery Blagdon are also relevant in this context: there is a contrast between the aspirations—the faith even—projected onto technology and the fragility of those assemblages. In a sense, we wanted virtual reality and high-tech components but a piece like Cattelan's is very much about diminished reality.

DBYes, it is definitely not the show that the MIT Media Lab or ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe would have done.

MGIt was important to us to remain modest in this show. Of course, we do include technologically advanced pieces such as Rosenkranz's robotic snake, Healer (Waters), but there are also many pieces that are very handmade. It is a tiny show and we wanted it to feel like a broken machine.

Everything was dictated by the size of the door, which we ended up making even smaller, otherwise, there would have been too much light coming in. These restrictions defined how we put this show together.

BLWIn the small room outside, Takis' Kadran Dial (1974) is the machine that looks back at you, and next to it is Cao Fei's Oz (2022), a highly rendered visualisation of a chimaera of some kind.

On the roof is one of my favourite works in the show, Hopf's sculpture. Within the context of Greece, the work reminds me of the attempt to avoid Medusa's gaze. But the figure is nonetheless petrified, so the deflection doesn't seem to work.

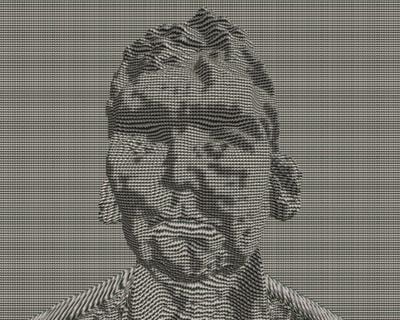

MGI am constantly surprised by how human gestures become common, often because of technology. People hold smartphones in similar ways. We all now have carpal tunnel syndrome.

The show indeed alludes to the relations that are developed between humans and machines as our bodies are trained to use technology. But it's not just the physical body, of course, it's also our nervous system that gets expanded and connected.

Looking at Hopf's sculpture of a phone user aiming her iPhone at the sunset, I am reminded of Régis Debray's comment that humans photograph things they fear to lose.

DBIn that sense, our show has a lot to do with old utopias. Old futures, so to speak. We do not join the apocalyptic doomsayers against AI, but also try to avoid a simplified optimistic perspective. However, I am surrounded by many who are incredibly optimistic that these new technologies will generate a new way to inhabit the planet.

If we see the art world as a microcosm of the world and its pathologies, we can witness the best and worst of humanity in it. There are many fears and some hopes. These technologies, I am thinking of Rist's video or Bul's AR piece, offer glimpses of new institutional possibilities. While small, they are all part of the show. And I am very happy about that.

If we see the art world as a microcosm of the world and its pathologies, we can witness the best and worst of humanity in it. There are many fears and some hopes.

BLWTo an extent, audience interactions with art have also undergone significant transformations due to the widespread adoption of technology.

While prints have long enabled access to artworks away from the original, nowadays, we primarily engage with art through reproductions. Even when physically in the same space, we still attempt to capture them with our pocket cameras.

DBIndeed. It's already the case that every second person looks at the artwork through a smartphone, whether as a reproduction on social media or to see the artwork itself.

But even if one avoids the smartphone and for example, comes live here on a remote part of the island to reconnect with reality, I believe it is our way of seeing that fundamentally changed. And I don't think there is any coming back from that.

MGAs a curator, it was a very challenging show to do—and by that, I mean it was an absolute pleasure. It's a small show, but I hope it's full of special findings.

I am not sure it would have been possible anywhere else. This also brings us back to the notion of utopias. In our field, we're encouraged to create new, grand, large-scale exhibitions that still emphasise the original artwork, which is something we should perhaps re-evaluate.

For example, it's possible that in 25 years, it might get more difficult to borrow paintings and fly them across the world. Factors like fragility, the need for protection, and restrictions on movement, all interconnected with the climate crisis, could contribute to this shift. In fact, these discussions have been taking place since the 1970s.

I recall an instance where a museum in Italy focused on metaphysical painting exclusively showcased copies presented as lightboxes. It didn't last, unfortunately. Dream Machines is a humble step in this direction: think small. —[O]