Miao Ying's Field Guide to Ideology

In partnership with University of Toronto Art Museum

Miao Ying. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Don Stahl.

Miao Ying. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Don Stahl.

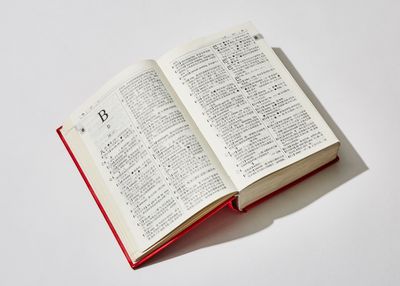

Miao's 2007 work Blind Spot, which indexed all the words in the Chinese dictionary blocked by google.cn, marks the artist's turn to censorship in China. The artist calls her relationship with China's hyper-regulated online sphere a form of 'Stockholm syndrome', a condition in which hostages develop a psychological alliance—a traumatic bonding, in her words—with their captors.

In A Field Guide to Ideology, the artist's first exhibition in Canada the Art Museum at the University of Toronto (1 February–2 April 2022), Miao humorously unpacks the architecture of this paradoxical condition.

The exhibition presents two fictional strategies via 'internet installations': browser-based online projects expanded into multimedia viewing stations that constitute a physical experience mediated by digital rhetoric and counterfeit ideology. Both projects combine internet slang, stock photos, popular memes, and viral videos sourced online, and are accompanied by computer animations made by the artist.

The first, Chinternet Plus was commissioned by the New Museum in 2016 as part of First Look: New Art Online. Defined by a 'counterfeit ideology', five sections of the website open with 'Our Story', which reflects on the 'challenges' of creating a 'counterfeit logo', and ends with 'Our Experience', where a YouTube video titled 'Post commentary, monetary likes and Morgan Freeman's advice on reality' opens with Freeman asking, 'Do we live in the real world?'

In Chinese, the English word 'paradox' or 'contradiction' translates into the two-character compound word 矛盾 (máo dùn), in which 矛 means spear and 盾 means shield, a literal confrontation between attack and protection.

Miao reads the flourishing popular culture on the Chinternet as a paradoxical field of 矛盾—with official acts of censorship as 盾 (shield, or protection), and the modes of resistance they inspire, carried out by the netizens and seen by Miao as positive self-censorship, being 矛 (spear, or attack).

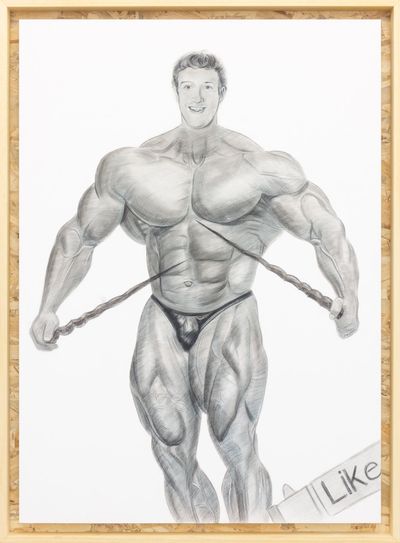

Commenting on Internet Plus, a recent Chinese economic strategy that involves the rebooting of traditional industries through cloud computing, big data, and lifestyle branding, Chinternet Plus (2016) is a parodic and critical take on the cultivation of a new, counterfeit ideology complete with media elements that she recognises as 矛.

Its companion piece, Hardcore Digital Detox (2008), is packaged as a caricature of the Western commodification of wellness, which Miao describes as a 'raw, healthy, hipster detox aesthetic.'

Commissioned by M+ in Hong Kong in 2018, the webpage instructs users to set their virtual private network (VPN) to mainland China so they can detox from restricted sites and apps like Google, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Netflix, eBay, and WhatsApp. The page opens with the 'HDD Manifesto', which unfolds as a long list of hashtags, from #spiritualretreatinchinternet to #nofilterbubble.

In Hardcore Digital Detox, Miao expands the notion of 盾 (shield) beyond the Great Firewall and redirects her criticism toward the phenomenon of internet filter bubbles—a state of intellectual isolation that results from the personalised results of search algorithms.

The project borrows a concept from traditional Chinese medicine 以毒攻毒 (counteracting one toxin with another), to juxtapose China's online censorship with the information filtering technology deployed by the billion dollar 'unicorn' businesses banned on the Chinternet, such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

Through these two projects, A Field Guide to Ideology exposes the internet as a complex space of hyperconnectivity where individual ingenuity provides a path of resistance against its pervasive corporate branding, global capitalism, political propaganda, and information censorship.

Together, they render a caricature of contemporary internet censorship technologies—China's Great Firewall juxtaposed against filter bubbles generated by social media platforms in the West.

In this conversation, Miao Ying talks to Yan Wu, the curator of A Field Guide to Ideology, about internet culture in China and its historical turns, and ideas that have informed works in this exhibition and how they have expanded into physical space.

Miao also discusses more recent projects, including Pilgrimage into Walden XII – the Honor of Shepherds (2019–2020), a live simulation game based on a utopian novel by behavioural psychologist B. F. Skinner, about a society where reinforced positive conditioning creates 'perfect behaviour'.

YWAs part of the first generation of internet artists in China, your perspective as an active netizen constitutes an important layer of your work, from Blind Spot (2007) and iPhone Garbage (2014), which involved you replacing the soundtrack to an official Apple iPhone 6 commercial with the sound of a man screaming about how iPhones are garbage, to Chinternet Plus (2016).

You belong to a generation that witnessed and participated in the internet's evolution in China since its inception around 2000. In your opinion, what have been the main stages of Chinese internet culture in the past two decades?

MYFrom the beginning of 2000 to 2010 when Google pulled from Mainland China, the internet in China had experienced a period that was relatively open and free.

At the time, most major Western platforms such as Google, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook were not blocked. I remember Wikipedia was one of the first to be blocked. For a while, you could log on the homepage, but you would be blocked if you tried to enter Chinese Wikipedia.

Perhaps it was a sign. At the time, besides Google, none of these platforms offered Chinese language interface. Some may have tried but failed—such as eBay—so only a small group of internet users in China who knew enough English were able to access these sites and the information they provided.

In 2010, Google China exited from mainland China. It could be considered the year that marked the rise of China's internet giants.

From the media to the creativity of netizens, China's technological environment is much wilder and more interesting than that of the West because of its lack of supervision and frantic change.

In the meantime, iPhones started to be replaced by an increasing number of domestically produced counterfeit smartphones with cheaper prices, which made it possible for most Chinese people to enter the age of personalised social media experience.

Prior to that, personal computers had been the privilege of internet cafes—mostly for playing games, with no private space—and urban dwellers.

My work has always been research-driven. The internet in China and its entire technological environment are fast-paced and ever-changing, so I must keep learning.

YWLooking at your work, one can sense a strong influence of the subculture and sub-aesthetics associated with the so-called diaosi—a self-deprecating Chinese internet buzzword used to describe low-income Chinese citizens—such as the shā mǎ tè subculture of rural youths whose style is a blend of goth, anime, and glam.

In Chinese mainstream culture, this group of people as a social and cultural phenomenon is usually described in derogatory terms, but in your work, they are depicted as a positive social force—a class of resistance with real power.

We can find them in Chinternet Plus, and can still see the aesthetic traits in the fictional characters in your later works. What do you think of this subculture?

MYWhen I returned to China from the United States after graduate school in 2010, I witnessed the shift of the internet in China from the relatively open period of web 2.0 during my undergraduate years to the rise of fully localised social media networks.

Since then, my attitude has also undergone some shifts. At the beginning, I despised local copycat technology companies, even with some resistance. Graually, I was impressed by the charm and humour of local netizens.

Compared to the talent and humour I found in their modes of 'self-censorship', I feel that my own work is dull. Hence, I became a humble observer of internet culture.

With the rise of We Media, my artistic interest immediately shifted from 'censorship' to 'self-censorship'. The most interesting and talented 'self-censorship' often comes from diaosi.

I was deeply fascinated by internet memes, self-made emoticons on WeChat, and bullet screens—a feature on online videos that allows real-time comments from users to pop up on the screen. I got to hear voices I had never heard before, and I could hardly watch any video without a bullet screen. Without them, the videos are simply boring.

I also realised that our times have shifted to an era of comments—the content itself had been replaced by comments. Bad reviews can also generate traffic.

From the media to the creativity of netizens, China's technological environment is much wilder and more interesting than that of the West because of its lack of supervision and frantic change. I became completely obsessed. The creativity that constituted the foundation of this shift didn't come from the elite but grassroots movements.

Aesthetically, I like 'low-tech' visual effects. They are poetic and inspire me to create. I like the moment when high-tech becomes low-tech—when the threshold of technology becomes low enough for everyone to cross.

It is at this moment that this tacky tool becomes worthy of attention. For example, the foolproof Photoshop-like software on mobile phones allows all amateurs to edit images.

In turn, absurd phrases and gibberish expressions are generated to deconstruct aesthetic signifiers and signified in an abstract, lyrical way.

YWThe two works presented in this exhibition, Chinternet Plus and Hardcore Digital Detox both started as commissioned online projects. First conceived in the form of a website, later expanded into an offline physical exhibition, they form what you call an 'internet installation'.

What is the relationship between the online and the offline in these two works? What kind of audience experience do you hope to achieve?

MYAs described in the title of the exhibition, A Field Guide to Ideology, the online part of the work acts as an ideological guide. Both projects are fictitious ideological strategies.

The way I was taught to learn ideology when I was young is through propagation—the central government distributed 'red head documents' to local governments. Then, level by level, the spirit of the documents was internalised. This kind of socialist ideological propaganda is very similar to capitalist lifestyle commercialisation: one story, a few adjectives.

Like Apple's experience store, there's a sleek website and then there are physical stores to experience the brand's qualities. Every aspect of the design, from boundless lightboxes to natural wood tables, amplify the brand's lifestyle.

I consider the online presence of my work a guide for the project's abstract ethos. In fact, it is a kind of visual form similar to PowerPoint presentations—in the same way that a higher authority disseminates its ideology to lower levels.

In turn, the physical installation becomes an enhanced version of the ideological guide, the installation of each project propagating the ethos of its website.

YWInterestingly, this exhibition is in part about translating an online project into an offline experience, but during the pandemic, many exhibitions and art events have been transferred online.

As a new media artist, especially an internet artist, what do you think of this most recent 'going online' craze? Do you see new possibilities?

MYYes, this is quite ironic. Art museums have finally realised the whole idea of being online. These choices have existed for a long time, but people are naturally conservative and resist them.

No one wants to take the initiative to leave their comfort zone, but in times like these, whether you are ready or not, you become part of it. It's not black and white. I never advocate for the absolute digital, and vice versa.

I consider the online presence of my work a guide for the project's abstract ethos.

YWI am curious about your studies at the China Academy of Fine Arts. You are not only part of the first generation of internet artists in China, but also the inaugural cohort of students that entered the New Media programme at the China Academy of Fine Arts, probably the first of its kind in the country.

The teachers who led the programme at the time were Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi, both considered godfather figures in the history of Chinese contemporary art. What did they teach you and what did you learn?

MYWithout the New Media programme and teachers like Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi, my life would have been on a completely different trajectory.

As the first cohort, we received the most attention and expectations. We had to pass the most rigorous painting exams to enter the programme with very little knowledge of contemporary or even modern art.

Most of us only heard of the name Duchamp for the first time in the New Media programme. To be enlightened by great minds at a young age is fortunate. We were taught software skills and directly guided by active, practicing artists.

Even in the West, I think it is rare to have better faculty and facilities than we had back then.

YWBoth works in this exhibition point to the existence of a censorship system and its different manifestations inside and outside China's Great Firewall, as well as the Stockholm syndrome between netizens and the censorship system, and expressions of this paradoxical attachment in respective contexts.

When making these two works, you, as a netizen, have also experienced a migration process, moving from a life inside the Great Firewall of China to one outside. How do you feel about that migration?

MYMy early work, Blind Spot-words censored by Google.cn (2007), was a unidirectional outcry. It was like striking a stone with an egg, but in the way the blind men in the parable of The Blind Men and the Elephant did.

At that time, the Great Firewall was still a singular, linear shield. After 2010, the internet in China was no longer the same. The wall is no longer there. From social media to the Social Credit System, it was replaced by a ubiquitous air.

Even when I was working on Blind Spot, I was still optimistic about China's internet and technology. It had all kinds of restrictions, but it provided most people with a platform to access knowledge and information.

Especially in China, this is of special significance. But since the launch of the Social Credit System, I feel myself becoming deeply pessimistic about technology. It is frustrating and sad.

YWIn your previous works, you take the position of an observer, mostly collecting and presenting aspects of existing internet culture.

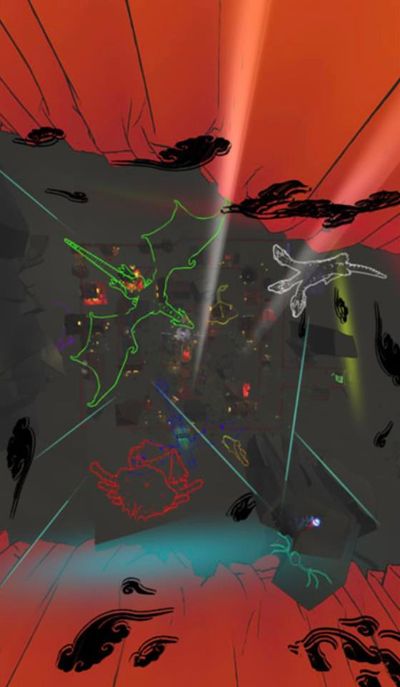

But in the latest work Pilgrimage into Walden XII – the Honor of Shepherds (2019–2020), you create a medieval fantasy game environment involving Artificial Intelligence and Big Data that seems to directly mirror the online world of today. Can you talk about this work?

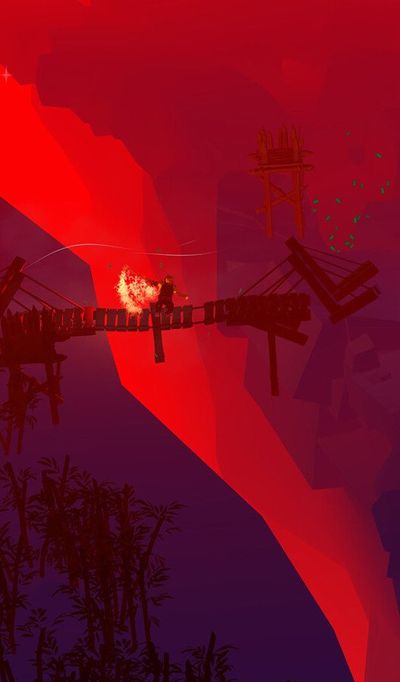

MYMy latest project Pilgrimage into Walden XII – the Honor of Shepherds is a game engine live simulation software of machine learning AI that can be run on computers and mobile devices.

The production is supported by a fellowship at Cornell University. Each year, they award one artist in New York an opportunity to collaborate with a team of technical professionals.

It is also my first long-term collaboration with technical professionals. Through nearly one-and-a-half years of running it, I have a more in-depth understanding of Artificial Intelligence.

I am fortunate to have a team of very supportive, open-minded, and generous collaborators, as I was literally changing plans every second.

What we have achieved is the most cutting-edge technology that no one has tried. In the end, we landed a perfect configuration and output through the gaming platform.

The Honor of Shepherds takes place in a medieval magical fantasy land called Walden XII—a place run by a digital indulgence system. Walden XII refers to Walden Two II (1948), a utopian novel written by behavioural psychologist B. F. Skinner.

In a structure similar to that of a medieval church, Walden XII is entitled to explain the ideological doctrine to its people and has implemented the technology to enforce citizen behaviour. It collects big data to then reward or punish citizens according to their score.

The work shows six Artificial Intelligence 'social shepherds', who represent different classes and different levels of intelligence. They are made to guard the Walden XII and shepherd the citizens, who are cockroaches.

Each shepherd's brain is trained on millions of examples of human-like movement patterns as a metaphor for big data and are scored according to a deviation from a set of ideal expressions.

Since the work is made of live simulations, the AI brains appear differently each time. Walden XII could stimulate a plausible future to our reality. —[O]