Michael Craig-Martin

Leading British painter Michael Craig-Martin was born in Dublin in 1941 and moved to the United States as a boy. He went on to study fine art at Yale before returning across the Atlantic to teach. At Goldsmiths College he influenced what would become known as the Young British Artists while developing his own works, which include super flat line drawings of powerful simplicity and eloquence. Our conversation took place on occasion of a major solo exhibition at the Shanghai Himalayas Art Museum, that gathers together over 40 new works.

Your great grandmother was from Wuhan, Hubei Province. Was China an influence growing up?

I grew up aware that my father’s family had deep connections in China, where he himself had been born. There were always Chinese objects in our house that had been passed down through the family. I was first in Hong Kong in the mid ’70s but I regret now that I did not visit Mainland China before the great changes of recent years. My grandfather bought a 3D camera in about 1905 and took many photos on glass slides. When I was invited to participate in the 2012 Guangzhou Biennale I had them digitised and projected there in 3D as an installation—a collaboration with my grandfather and a chance to bring these memories back to China.

Your work seems to speak a universal, globalised, commodity culture language. But do people really respond to your works similarly in different parts of the world, or have you identified differences and dialects in the way people speak the language of line drawing?

Line drawings have been made in every major culture since the Stone Age. There are of course differences between cultures and historical periods and styles of drawing, but I have never found that people have difficulty reading such drawings despite their differences. When I go to a cornershop in Newcastle, I have difficulty understanding the local dialect of English. Line drawing is not subject to such localisms.

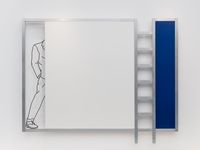

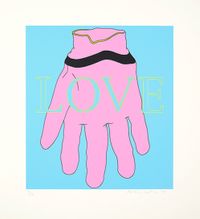

Exhibition view, Michael Craig-Martin at Shanghai Himalayas Museum

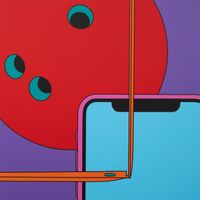

You’ve been making line drawings since 1978, and you’ve been so prescient about an emerging contemporary visual language that some people find it hard to see the work as in anyway outside mainstream culture. The works look like vector drawings, cartoons, instruction booklet diagrams, logos and app icons. They’re so flat they could be digital, and even the square format makes them seem custom made for Instagram. How would you respond to the Chinese friend of mine who saw them, liked them, but wondered “where’s the art?”

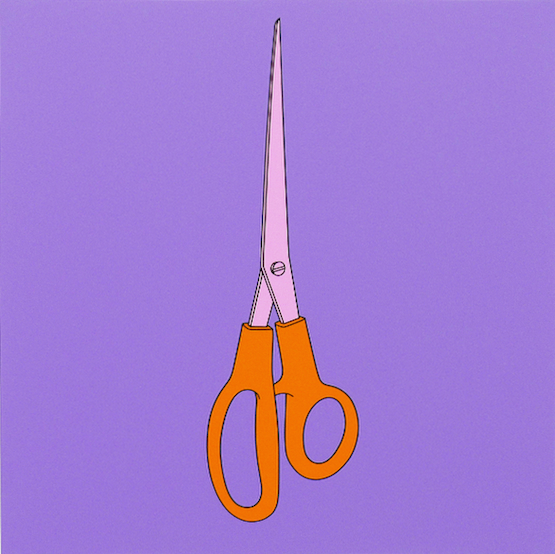

The look of my drawings is not an accident. From the beginning I wanted to have precise accurate drawings that would have the same character as the fabricated objects I was drawing. I assumed they existed in mainstream culture and was very surprised to discover they didn’t, which is why I started to make them myself. My drawings are traditionally observational, each made by looking at a single object. I want my drawings to seem so obvious they ‘disappear’ leaving only the object. I have never sought to make drawings that look like ‘vector drawings, cartoons, instruction booklet diagrams, logos and app icons’ though these sometimes look somewhat like my drawings. I sought originally to make drawings that were styleless, but ironically they are now recognisable as my style. If your friend cannot see the art in what I do there is nothing I can say to help.

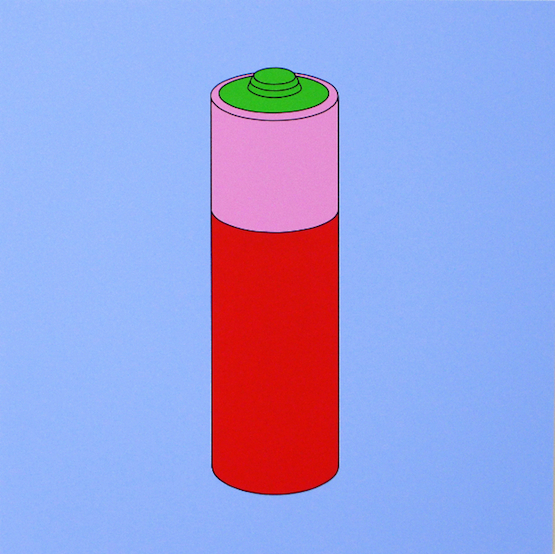

Michael Craig-Martin, Untitled, acrylic on aluminium, 2014. Image: Sam Gaskin.

The color blocking also seems to anticipate the iPhone 5C, Uniqlo, Pentax cameras, etc. I spoke to a designer who said changing a product’s color is especially common during recessions, when more expensive changes to designs are not practical, and consumers want to defy austerity. Do you see your color selection—sparking with dissonance—as somehow a reaction against the banality of the objects themselves? What influences your color choices?

I am an artist not a designer. I make paintings not objects. I have developed my use of colour over many years: a full but limited palette of basic colours—red, yellow, purple, blue, etc. I want my paintings to have as intense a physical presence as possible. By their nature all reproductions of my work emphasise its graphic quality, which is of little interest to me. The meaning and impact of the work is only clear in its physical presence.

You have said that the functions of objects in the 2010s are much more disguised than they were in the ’70s and ’80s. But they also more precisely belong to their year, I think; it’s no longer just cars and fashions that visibly change annually, but models of cameras, phones, headphones, etc. Is there an archival aspect you enjoy about your work, thinking about how our evolving objects reflect on us, and imagining future audiences looking back on them?

I make my work to be seen now. It is impossible to predict how it may appear in the future. I would like my paintings to come to feel timeless, despite eventual datedness of many their subjects.

Michael Craig-Martin, Untitled, acrylic on aluminium, 2014. Image: Sam Gaskin.

The show is curated so that text and image are never alongside each other competing for attention. You’ve said images are a foundational language, more powerful than words in many ways. How did you arrive at this perspective? Why do you think we are so slow to perceive images’ semiotic, referential power?

I have always been more comfortable with the visual than the verbal. Ironically, although the visual world has become increasingly dominant over the past 30 years, people’s ability to look has deteriorated. Pictorial language is not only the basis of all written language but that of perception itself.

Line drawings are very functional despite their aggressive levels of excision and abstraction, offering none of the shading, texture, dust, uneven light, or surroundings for scale, etc, that we receive in the real world. Eloquent, you could say. What are the limits of this sort of reduction? Do you see line drawings’ ubiquity as symptomatic of a culture grappling with a rapid rise in complexity and an excess of information?

I see line drawing in terms of a particular type of focusing rather than as reduction. Every drawing involves choices about what to show and what to leave out. When I make a drawing of an object it is not possible or desirable to try to include every detail but I do try to achieve that level of detail necessary to allow an understanding of the object from the image. As far as possible I do not abbreviate or approximate. Line drawing is perfect for what I try to do.

Michael Craig-Martin, Untitled, acrylic on aluminium, 2014. Image: Sam Gaskin.

You’ve said that one of your greatest motivations in art is to see something brought into being that no one else would make. Is that still a major motivation? Does that necessitate this series of work somehow evolving?

Though aspects of the world have increasingly come to look like my work I don’t think anybody makes work like mine. The only way to see something from one’s imagination is to make it oneself. When I started making drawings of objects it never occurred to me that this might become the basis of my life’s work, but it has. I have no sense of having exhausted the rich seam I opened so long ago.—[O]