Tracey Rose on Conveying Outrage with Humour

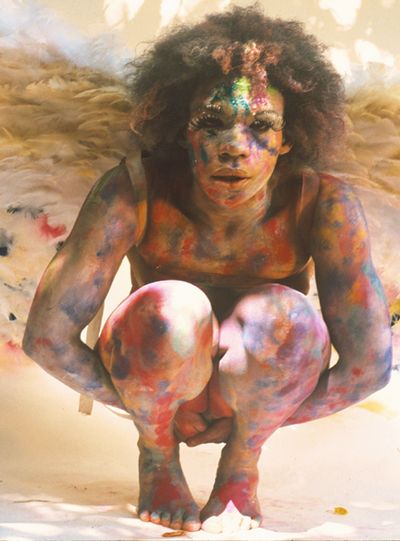

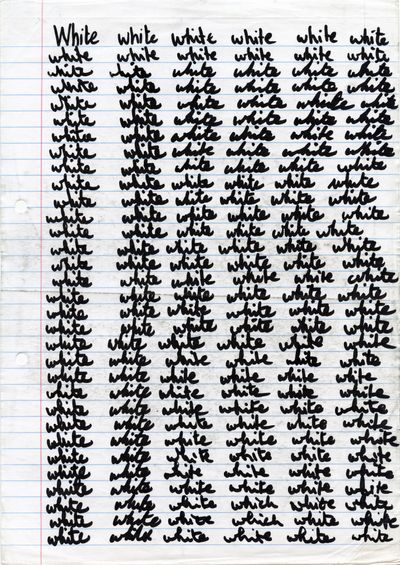

Tracey Rose. Courtesy Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa.

Tracey Rose. Courtesy Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa.

In the durational video work TKO (Technical Knockout) (2000), artist and protagonist Tracey Rose delivers blows to a punching bag fitted with spy cameras. As the performance progresses, her image gradually disintegrates.

It is a powerful and provocative work, typical of an artist who over the past three decades has used a range of mediums, particularly performance, to deliver groundbreaking works that express her outrage at sociopolitical inequalities.

Transcending challenges as a young artist growing up in post-apartheid South Africa, Rose has shown work in major international exhibitions across the globe, including three editions of the Venice Biennale (2001, 2007, 2019); Africa Remix, Hayward Gallery, London (2000); Lyon Biennale (2011); São Paulo Biennial (2016); Dak'Art (2000); Performa 17 (2017); and Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019).

Most recently, Rose is the subject of the comprehensive retrospective Shooting Down Babylon (23 April–10 September 2023), on view at Queens Museum, New York, having travelled from its first showing at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town (19 February–28 August 2022).

The exhibition brings together 30 years of work, tracing Rose's trajectory from her early works probing narrow identity tropes to her interest in the aesthetics of violence, her subversive performative explorations, and, more recently, a focus on processes of healing and rituality.

The show encompasses film, sculpture, photography, performance, print, painting, and multi-layered participatory works, including seminal pieces such as the 'Ciao Bella' (2001–2002) and 'Lucie's Fur' (2003–2004) series, as well as large-scale, site-specific sculptural works such as Tower #1 Caryatid #1: Made for Hoerikwaggo (2017).

The latter, situated in the Queens Museum lobby for this iteration of the retrospective, comprises a red painted pillar that references the devastating impact of Dutch colonial violence in the South African landscape and psyche.

Ciao Bella (2001), Rose's work for the 49th Venice Biennale, unfolds as a vignette where the artist adopts the role of a griot—an African tribal storyteller/musician whose role was to preserve the genealogies and oral traditions of the tribe.

The three-channel video installation and accompanying photographic portraits see the artist portray 12 characters based on feminine archetypes ranging from porn star Cicciolina to Nabokov's Lolita; French monarch Marie Antoinette to South African Saartjie (Sarah) Baartman, who in 1810 was taken to Europe and exhibited in the 'human zoos' that were popular at the time.

Rose rejects the degradation and undermining of the agency of these women and others, and through restorative rituals afforded by the trope of masquerade, she reimagines their lives in the present, creating a parody of Da Vinci's Last Supper, with the original male roles recast as female.

Also referencing religion is the photographic series 'Lucie's Fur' (2003–2004), which traverses tropes related to the myth of creation and turns stories upside-down: Adam and Eve become Adam and Yves, Jesus becomes a gay South African woman, and Lucifer becomes Lucy.

Rose's use of art to problematise notions of difference that rely on a binary of invisibility and visibility and her strategies of disidentification recall scholar Jennifer Doyle's book Hold It Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art.

Like Doyle, Rose's work encourages viewers to examine the ways in which works of art challenge how we experience not only the artist's feelings, but our own.1

In the conversation that follows, Rose rejects labels and narrow framings of her approach to artmaking, reinforcing the transformative qualities of ritual in her practice. She notes the critical role of performance—as a potent force for conveying humour as well as outrage, while operating as a mode that allows transformative approaches to being in and understanding the world around us.

JDI first encountered your work at Africa Remix at the Hayward—watching your video TKO (Technical Knockout) (2000) was transformative for me as someone who was building an interest in performance art. Can you discuss this work?

TRI was working within a space where I was interrogating the work conceptually, with long periods of research before executing it. TKO is a good example of this kind of work, insofar as that I had the idea two years before I made it.

I created it during a residency at Artpace San Antonio, Texas, in 2000. It was initially conceived for a post-apartheid group exhibition which was showing a majority of white South African artists. I was so angry about the concept of the show that I had the idea to stage a boxing match. This led me to join a professional boxing gym in downtown Johannesburg, and I kind of fell in love with the sport and the emotions it revealed—anger, exhaustion, ecstasy, and so on.

I started asking questions about boxing going beyond being a sport; it allows you to surpass yourself with an almost out-of-body experience. When that happened, I found it interesting and decided I would use it in my art practice at some point.

Where did you see TKO? In Africa Remix in London or Johannesburg?

JDIn London, at the Hayward Galley, in 2005. I was in my 20s and an art history student at the University of Leeds; the trip was organised as an introduction, of sorts, to contemporary African art.

TRI felt it didn't have enough space there, in London, but in each location for the touring exhibition, it was always shown differently. It is supposed to be shown in a square format with a tilted, diagonally slanted screen that's double-sided and a rear projection video, so the viewer walks around it.

When I got to Artpace for a two-month residency, I was avoiding making TKO as I knew it would be incredibly draining and intense, but then two weeks before the opening, I decided, I'm making this work, and it just spilled out of me.

The repeated action of punching was a conversation with mark-making, a homage to Monet's 'Water Lilies'; the squared-off format of the boxing ring transformed onto a 2D surface, a homage to Cubism. You know, the kind of mark I made and part of the reason I didn't paint was the fact that the materials were too expensive, and I didn't have a studio. I started doing performances as they served as the most effective medium.

The performance was recorded directly onto VHS tapes and then digitally edited, with the translucency and opacity of each layer adjusted. The format changes from analogue to digital caused the image to corrupt—in parts you can see pixelation which is the nature of the medium and a Rodin 'truth to material' moment.

The installation was conceived to be in-the-round, so the audience relationship is interfered with as they move around the screen, either blocking the projection and casting a shadow on it or in being confined to a smaller space, with barely enough room for more than one person to pass by at a time. The viewer implication was an important component.

JDHow have rituals ranging from exorcism to birth, strategies for resistance, and shamanism served as a tool for artmaking and world-building within your practice?

TRRituals are a way of thinking through and dismantling both rigidity and sanitation of the works, in a sense, and with shamanism as well, these become disruptive ways of permeating a particular way of reading, contextualising, and framing the work. I was curious how rituals and shamanism offer ways of building new worlds to experience the kinds of works I was making and continue to make.

JDIn your practice, I see not only a rich, ritualistic, and non-conformist approach but also strategies of resistance that allow for alternate worlds to exist. I also think the wound as a metaphor is an apt way to read some of your work. This suggests notions of healing and how artists can adopt the role of both griot and shaman for our times. Would you agree?

TRIn relation to TKO, I made a work because I was angry, and I wanted to bust something up. Now I ask, how can I do something to resolve the rage, the frustration, or whatever it is? I turn my rage into work that has a formal gesture, and each work has its own life force.

Sometimes the best way to realise the work is through photography or video, or a performance, drawing, or sculpture. I ask, can I use this as opposed to that? How can I make this? How do I justify this? What does this mean?

Maybe this is also tied to a question around performance and duration—when you go through a process of wearing down the body, alongside this, there is rage, rebellion, outrage—but humour is a device as well, because laughter is medicine, right? So, it can appease a violent reaction, because that's also a thing to navigate—how the audience reacts. So how do you say things that are triggering, but also get away with being so?

I was thinking when you were talking about wounds and healing, about an epiphany I had a couple of months ago: There are around eight billion people in the world, and around one billion people are white, yet as the group who have had a lot of the power, they've managed to oppress many non-white populations through instruments such as colonialism and slavery, and contribute to the destruction of the planet too. Historically, and in some parts of the world today, non-white populations have essentially been a service industry for white pleasure. And until a recognition of our self-worth happens, change will not occur.

You can do whatever art you want, but the biggest delusion we've been sold as Black people is that of trying to assimilate and do the work for whiteness. I'm done with that because I felt like a lot of my early work was trying to educate whiteness about an alternative way of being and thinking. I wanted to go there and fix some shit, and then I realised, damn it! I'm standing here as a freak to get you to understand me and see me as something other than a freak, and I'm endorsing that.

Right now, for me, it's about stepping back and thinking of other ways to put forward an alternative ideology, and I'm still trying to think about how to do that, but I am leaning towards pop culture; how to occupy pop-cultural spaces—a platform like movies and the accessibility it allows.

JDThe complexities of selfhood, identity, and how one experiences and moves through society are areas that permeate so much of your work. How have you navigated teaching the next generation of South African artists at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg?

TRWe have mostly Black students in our institution, which was not the case when I was a student in the 1990s.

What I find frustrating now is, while the institution was founded on the white, male supremacy of the late 1800s, aspects of the learning experience have now been dissolved. For me, it is racist to assume that African students don't want to learn about the (Italian) Renaissance. Work needs to be done on determining what the art historical narrative should be. Making a start on this would be an important beginning. Excluding African art from any art history class is as bad as excluding the Italian Renaissance, and it's not just to do with racism: the whole world is missing out on incredibly valid and valuable information.

JDSince her time as Executive Director and Chief Curator of Zeitz MOCCA, Koyo Kouoh has foregrounded in-depth solo exhibitions centring Black women artists including yourself, Senzeni Marasela, and Mary Evans. What are your thoughts about the lack of in-depth exhibitions until recently on Black women artists' subjectivities in the global art world?

TRMy practice, like many other Black women artists, has been going for decades. But as you know, the attention comes when somebody like Koyo, who's invested in these practices, platforms them.

When she asked me to stage the show, I was at a point where I was thinking art is an expensive hobby and I've had enough. I was seeing a lot of mediocre work being celebrated and many of my peers and friends dying or dead, and others penniless.

Initially we had under a year to pull the show together, then Covid hit and in South Africa we went into a hard lockdown, so the show had to be delayed and then delayed several times more. At one point, I thought it wasn't going to happen at all. On the other hand, it feels as though there is a zeitgeist moment at present in the so-called art world; that it is ready for a particular type of confrontation. This is so wonderful to see, as a lot of 1990s artists are spotlighted and, for me, this generation is an important contributor to 21st-century art. From the space that I come from, there has been so little art historical recognition of this period and just of art in general.

JDThe current exhibition covers 30 years of practice spanning performance, film and video installation, sculpture, photography, print, and painting. What has it meant for you, looking back, and looking forward, in a context shaped by an intersection of identity, radical feminism, parenthood, and post-apartheid South Africa?

TRTo clarify, it's not 30 years of my professional practice but includes work that I have created before I started practising professionally in 1996. For example, there's work in the show from when I was in high school.

I've never intentionally wanted to align myself with any kind of categorisation, even though circumstances over time do force art/artists into categories. I think there's an assumption that the work has a set logic behind it, but I'm working, like many artists, intrinsically. So, people might say, oh, your work is about feminism or postcoloniality, but I never made work thinking, this is going to be about feminism or postcoloniality.

Some people don't care about postcoloniality or feminism; people read the work in a way that's peculiar to them—but it's still a reading of the work that's valid.

I think that in the last 20 years, art has become more concerned about what categories and frameworks fit rather than paying attention to the actual work itself. It is more important that I'm regarded as an artist rather than a 'feminist' artist, for example. I'm more concerned about the artwork and the artist as a healer or shaman. This means that I'm looking more to early art practices, to a time when humans painted on cave walls and were motivated by a drive to create.

I'm interested in understanding art as a profoundly spiritual tool and device that can initiate fundamental change that is not just superficial. And I mean fundamental change within the human being who is experiencing it, that is, the audience. This has always been the foundation of my practice, the very seed of it, and knowing that it is bigger than just a simple gesture and bigger than social commentary. —[O]