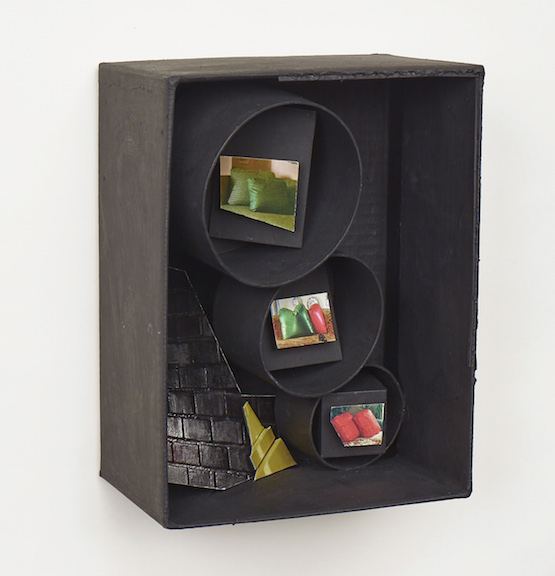

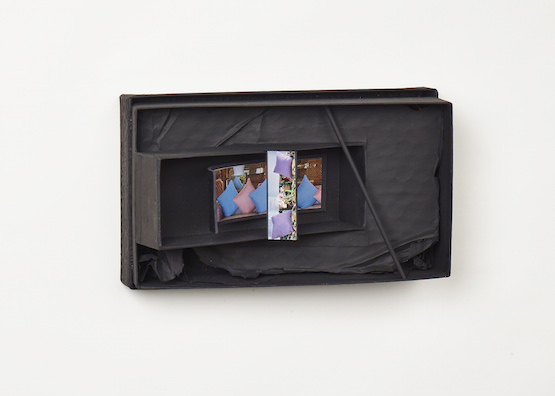

Vincent Fecteau

Vincent Fecteau. Photo: Philipp Hänger

Vincent Fecteau. Photo: Philipp Hänger

Based in San Francisco, Vincent Fecteau graduated from Wesleyan University in 1992, and has since developed a singular practice around '360-degree sculptures', in which form is treated as a series of elegantly interlocking tangles. These are either hung on gallery walls, or positioned on plinths.

Fecteau's sculptures are akin to visual riddles, their gaps and curves not leading anywhere, yet still achieving compositional balance—a tension that was explored in the artist's 2015 solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, You Have Did the Right Thing When You Put That Skylight In. The exhibition's title is from an Arthur Russell track: a song from the only album this avantgarde composer and musician managed to make in his short lifetime, which celebrates the way a skylight made the home of Ernie Brooks 'a nicer place to be'. The reference to the song connects to Fecteau's own interest in architectural and domestic spaces, and recalls something Fecteau said once about the way an artwork bears the 'complicated psychology of a housewarming gift.'

Fecteau discusses the exhibition in this interview, along with the complexities of art-making and the importance of following one's intuition.

The exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel is your largest to date, bringing together works from 2000 to 2015. How do you feel about this overview of your practice, from then to now, when considering the spectrum of work in this show?

For me, it's a show that includes a sizable group of new work and some older sculptures. I don't really think of it as an 'overview'. It is, however, an amazing opportunity to have a look back at some things that I've made in the past and see how they might interact with and inform the most recent things, which although materially related to some of my earliest work, are very much about my present state of mind.

You have said that both your sculpture and collage works 'tickle the same part of your brain' and essentially talk about the same thing. What part of the brain, and what thing?

I'm not sure how to answer this question. I think things can operate on several levels. There is the content that can be articulated and then there is that essential 'thing' that is deep within one's work that, I think, is fundamentally unknowable. This is what makes the whole process so compelling and yet also a bit sad.

You have said you often work on a sculpture until it no longer irritates you: is that the moment the work has finally articulated the essence of the mood or thought you were seeking to articulate through the process of making?

Probably, although nothing ever feels that fixed. It's not as if when I finish something I feel like I've figured it out. For me, the process feels much more unstable than that.

In conversation with Phyllida Barlow, you said that 'it's sculpture's triumph that an image, or even a thousand images, will never replicate the experience of a sculptural work.' I wonder if you could talk about this idea, considering the fact that you also said you 'long for the form that exists free of so called understanding and that operates in a purely abstract, maybe unconscious way'?

Art-making should be aspirational. Too many other things in the world are perfectly happy to be 'Instagramable'.

You have talked about a belief that art has the potential to offer us access to essential and unknowable truths. How would you describe some of those truths you have encountered through making work?

Of course I think these truths are different for each person. For me they're existence is real because they are most often accompanied by a strong physical and emotional sense of connectedness and compassion.

You once talked about sculpture bearing the 'complicated psychology of a housewarming gift.' Is this a way to think about the art you make?

Yes. I don't believe in completely 'pure' impulses. Generosity and hostility often go hand in hand. My relationship to the making, showing, and selling of work is likewise, 'complicated'.

Here, I also think about Arthur Russell, and the fact that the song that lends its title to this show talks about a skylight that makes a home 'a nicer place to be'. I wonder if this relates to the idea of the artwork as a psychologically complicated housewarming gift you would want someone to want?

I was listening to a lot of Arthur Russell as I was working on this show. I hardly ever know what a song is about as I rarely pay attention to lyrics. But something about these particular lyrics really caught my attention. They were casual and kind of slight but also had a strong emotional pull. And when I heard that the Kunsthalle Basel had a beautiful glass ceiling I felt that I had no choice but to use this for the title.

If you could offer any advice to young artists working today, what would it be?

I would recommend not going into large amounts of debt for an MFA. There are many ways to be an artist and sometimes the least obvious ones turn out to be the most interesting.

If you could offer a viewer hints as to read your work, what would they be?

I would like to encourage people to just look and trust their intuition. People are much more visually astute than they often give themselves credit for. It's a failure of our art institutions that people don't feel like that have some inherent ability to appreciate art.—[O]