Aesthetic Radicalism in ‘Awakenings’ at Singapore’s National Gallery

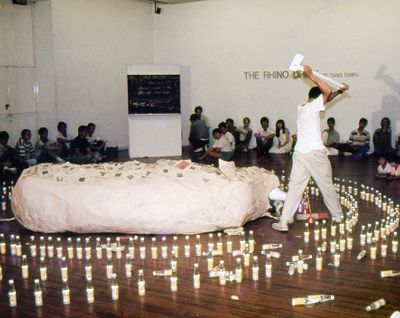

Documentation of Tang Da Wu performing They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink (1989). Courtesy Koh Nguang How.

Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s–1990s, a major retrospective at Singapore's National Gallery (14 June–15 September 2019), opens emphatically in flames. At the exhibition's entrance, viewers encounter a wall-sized image from 1964 titled Burning Canvases Floating on the River. The photograph captures a performance by Lee Seung-taek, in which he took three figurative oil paintings, set them alight, and cast them adrift on the Han River—a kind of Viking burial for outmoded ways of art making and in defiance of the martial law South Korea was under at the time. Lee abandoned the canvases as they floated off towards the North Korean border, not sticking around to get nicked.

Burning Canvases Floating on the River is a good illustration of the exhibition's intentions: to shine a light on Asian artists' strategies for enduring the social and political fallout of the Cold War—from decolonisation and backsliding democratisation to rapid economic transformation—while elucidating the ways artists have pushed boundaries on what they could say and how they could say it at the time.

Organised in collaboration with the Japan Foundation Asia Center, the National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea—the latter two having already staged versions of the show—this ambitious exhibition is the result of an eight-person curatorial team's visits to 17 cities across Asia, from Tokyo to New Delhi, Beijing, and Yogyakarta. During more than four years of research, 142 works by 100 artists were gathered, the majority of which coming from East and Southeast Asia.

Dr Eugene Tan, the director of National Gallery Singapore, describes Awakenings as an exhibition within a trajectory that has 'decentred Euro-American art histories by foregrounding the art histories of Asia.' Considering the moment when modern art transitioned to contemporary art, a chronology complicated by the fact that different Asian nations underwent this transition at very different times, the exhibition is consequently structured thematically, not chronologically, under three broad chapters. 'Questioning Structures', 'Artists and the City', and 'New Solidarities' collectively look at how artists expanded the boundaries of what constitutes art, made use of quotidian materials and their own bodies, critiqued consumerism, stood up for marginalised groups, and endured censorship and imprisonment.

'Questioning Structures' focuses primarily on artist structures, avantgarde artistic practices that challenged aesthetic conventions, and social structures. Like Lee Seung-taek's Burning Canvases Floating on the River, fellow Korean artist Quac Insik attacked the canvas as an emblem of old art in Work 63 (1963), a piece of glass smashed over canvas, giving the appearance that the surface itself had shattered.

But not only does 'Questioning Structures' show frustration with old modes of art-making; it also confronts local audiences' lack of interest in contemporary art. Thai artist and artistic director of the 2018 Bangkok Art Biennale (Beyond Bliss, 19 October 2018–3 February 2019), Apinan Poshyananda, tried to win them over with humour in his work How to Explain Art to a Bangkok Cock (1985)—a video of the artist attempting to teach art history to totally uninterested poultry that references Joseph Beuys' How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965).

Performance art was both an avantgarde form and a crucial method of art-making in several Asian countries, where materials were hard to come by and objects could be destroyed by censors, serving as a powerful means to express vulnerability and frustration. Korean artist Kim Kulim's land art piece From Phenomenon to Traces—Event With Fire and Lawn (1970), is represented with photographic documentation of large triangle shapes burnt into the grass and slowly returning from black to green over the days that follow; as is Japanese artist Hitoshi Nomura's DryIce (1969), which involved the artist recording the weight of dry ice blocks as they melted, making his notations in white on the long black rubber mat which the ice sat on, shifting the dry ice forward each time to make room for new marking.

Works using the body as media include video documentation of Yoko Ono's provocative Cut Piece (1965), in which she invited the audience to snip off parts of her clothing, and Lee Kun-Yong's The Method of Drawing 76-2 (1976), in which the artist tried to draw himself with a marker while lying with his back against the artwork's surface, a piece of plywood.

The second chapter of the exhibition, 'Artists and the City', largely centres on works that critique media manipulation, capitalism, modernisation, urbanisation, and the influx of consumerism. Huang Yong Ping's installation Reptiles (1984) is comprised of traditional Chinese tombs made of French newspapers pulped in three washing machines. The washing machines themselves are displayed too, alongside a tall column of papier-mâché-like gunk flung at the walls. The work, which suggests cleaning information as a way to destroy it, forms a fine dialogue with fellow Chinese artist Zhang Peili's Water: Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary (1995), in which state broadcast anchor Xing Zhibin lends the authority of her delivery to an utterly meaningless recitation of words from the Cihai dictionary beginning with the character shui, meaning water. Both works imply a degree of 'brainwashing'—a metaphor that is as popular in Chinese as it is in English.

While accurate information isn't always easy to come by, China's e-commerce revolution has made a vast variety of global commodities more easily accessible in the country, which wasn't always the case. Wang Jin charted the extent of unmet desire in Ice 96 Central China (1996), a performance documented in photographs in this exhibition. In central Zhengzhou, Wang Jin built a 30-metre-long wall of ice with over 1,000 consumer products, including TVs, watches, phones, and leather goods, encased within it. The crowd's eager smashing of the ice to get to the items inside was unplanned.

The most prominent performance work in the exhibition is experienced as an installation. Singaporean artist Tang Da Wu's They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink (1989) comprises an axe and a linen Rhino carcass surrounded by a spiral of plastic bottles for Three Legs Cooling Water, a traditional Chinese medicine drink that uses the image of the rhino in its branding. A video displays Tang Da Wu's performance, originally held at the National Museum Art Gallery and the Singapore Zoo in 1989, in which he dressed up in white as the ghost of the rhino and swung the axe at the bottles as a gesture of resistance against the perpetuation of the myth that the horn of the rhino has cooling properties when consumed.

Though it may have harmed fewer rhinos, no other mass-consumed drink is more maligned by artists than Coca-Cola, with the drink featuring prominently in a few works. The drink serves as an emblem of resentment at America's continuing presence in Korea decades after the Korean War ended in 1954, with the U.S. military's United States Forces Korea (USFK) finally moving the majority of its troops out of Seoul in 2018, when its headquarters shifted to Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek. Korean artist Park Buldong's Coca Cola Molotov Cocktail (1998) consists of a photograph of a Coke bottle with a torn U.S. flag for a fuse; Park was a member of the Reality and Utterance group that formed in South Korea in the late 1970s to make blunt statements about the world without the idealism or visually pleasing aesthetics as tradition had previously dictated.

Also giving a beating to the Real Thing is Indonesian artist Arahmaiani, whose Sacred Coke (1993–2016) shows a bottle of the drink topped with a condom and surrounded by white powder, playing on the words 'coke' and cocaine that reveal intersections between consumerism and drugs perpetuated by capitalism.

Sacred Coke treats this ubiquitous soda as a symbol of sex, drugs, and broader social decay brought on by the acceleration of global consumer culture—a theme that is also referenced in compatriot Jim Supangkat's sculpture, Ken Dedes, from 1975. The work shows the plaster bust of the eponymous mythical queen, considered the embodiment of beauty in Javanese tradition, plus a drawing in black marker on white-painted wood of a woman's torso and legs wearing unzipped jeans.

Part of the Indonesian New Art Movement (1974–1989), which criticised decorative art and attempted to replace it with the contemporary artist's toolkit of installations, ready-mades, photographs, found objects, and so on, Supangkat sought to critique Indonesian President Suharto's economic policies, conceived by Indonesian economists educated in the U.S. and that saw a steep increase in foreign direct investment that brought with it Western influences and values.

The third and final chapter of the exhibition, 'New Solidarities', is strongly represented by artists from the Philippines, and questions the way female bodies are presented and the roles they are expected to fulfil, collectivism, and the reinterpretation of histories. Julie Lluch's Thinking Nude (1998) is a terracotta sculpture of the artist examining herself in the mirror, contemplating an honest, unidealised depiction of herself that includes her C-section scar. The work forms a kind of diptych with Imelda Cajipe-Endaya's Sa Plantsahan ni Marra (At Marra's Ironing Board) (1992), a painted wood and plaster-bonded cloth sculpture of a woman's dress standing at an ironing board, with which it is shown back to back.

The only work addressing LGBTQ identities in this show is Nick Deocampo's Oliver (1983), a video of a male sex worker performing in drag. Exhibition co-curator Seng Yujin calls this the only 18-rated work in the exhibition; a reflection of the little progress that has been made concerning LGBTQ rights in the region, with Taiwan becoming the first Asian country to legalise gay marriage just this year.

The final works in the exhibition examine the re-politicisation of art after years of artistic suppression. Burmese artist San Minn's euphemistically titled painting Building (1979), for instance, depicts Yangon's Insein Prison, home to thousands of political prisoners over the years, including the artist himself—San Minn was jailed for joining the 1974 student protests over former UN secretary general U Thant being denied a state funeral.

Concluding the entire show is Indonesian artist FX Harsono's What Would You Do if These Crackers Were Real Pistols? (1977–2018): hundreds of pink gun-shaped wafers piled into a loose pyramid and a desk on which audiences can write their responses. It's a work that many have associated with former Indonesian President Suharto's military junta, but also makes the violence of the past seem less remote, especially with Rodrigo Duterte championing gun violence against drug users in the neighbouring Philippines. The installation mirrors another FX Harsono work located in the opening section of the exhibition, which best anticipates the period canvassed in Awakenings, and beyond: a thick steel chain that binds a mattress and pillows titled The Relaxed Chain (1975/2011). Being oppressed, the work suggests, has become more comfortable under global capitalism, with too many having relaxed into the intellectual armchair of nationalism.

Asked if the period covered by Awakenings indicates a high-water mark for artists' political engagement, and even for democracy and liberalism in the region, co-curator Adele Tan says she refuses to be so defeatist. 'We have to get cleverer,' she says. 'We have to find different tactics. We have to manipulate right back...'

In what seems to be a new era of intra-Asian colonialism, plagued by debt-trap development deals and cynical island-building meant to gerrymander territorial waters, Awakenings offers a handbook for today's artists brave enough to make socially engaged art when governments and the art market are more likely to reward anything else. Consider Singaporean artist Charles Lim's project Sea State 9: A Proclamation Garden (2018), currently showing in the Gallery's rooftop garden. The work presents weeds taken from reclaimed land projects around Singapore that have hoovered up so much sand from surrounding countries that many now refuse to sell it to them.—[O]