'Creating Abstraction' Connects Seven Artists Across Generations

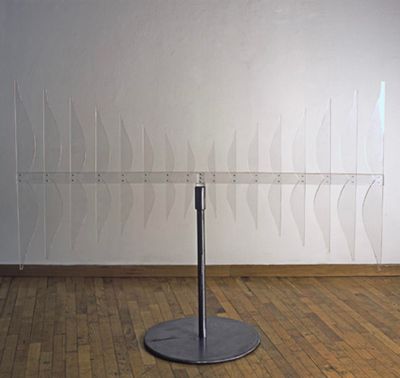

Exhibition view: Creating Abstraction, Pace Gallery, London (3 February–12 March 2022). Courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

The limits of what can be rendered through abstraction are not clearly defined. Indeed, the thought of representing indistinct shapes, ideas, concepts, language, and emotions by transposing them into a visual display may even present a paradox.

It is more rewarding to focus on the processes and methodologies of abstraction, as highlighted in Creating Abstraction at Pace Gallery's new London space in Hanover Square (3 February–12 March 2022).

Despite being born during different decades and operating in separate parts of the world, seven women artists are connected by a shared atmosphere of experimentation and a mutually held regard for material transformation across a constellation of 62 works.

Constructed from perspex and metal, Scultura trasparente (2002) by Italian artist Carla Accardi, associated with the Arte Povera and Arte Informel movements, opens the show. Arranged like an aerial transmitting light frequencies, shards of plastic on metal supports gradually decrease from left to right before enlarging again, like light passing through a prism.

Accardi's Verde rosa (2010) and Arancio azzurro (2010) sit in the gallery basement. Freestanding plastic and plexiglass layers are rolled into two cylinders, each illuminated by a bulb exposing overlapping brushstrokes in shapes that resemble alternating wavelengths—green and pink lines in one, orange and blue in the other.

Accardi's two paintings Fondo Rosso (1959) and Oscuro Paradosso (2013) hang beside Verde and Arancio, further demonstrating the artist's pioneering treatment of light and colour. In the latter, forms take shape through both the application and omission of casein and vinyl paint.

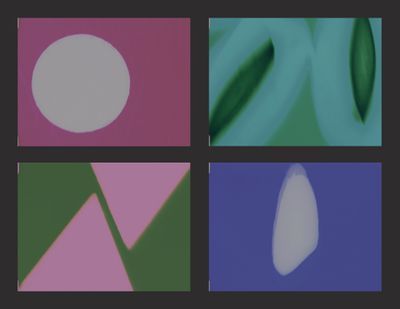

Responding to Accardi's manipulation of light and shadow in the basement, is contemporary artist Yto Barrada's video installation Horsehair, Confetti, and Rice (2019), which transforms the flimsy materials from its title into pliable, geometric shapes.

Concealed behind a three-panel folding screen by Barrada (A day is a day, 2020), each frame shows a different configuration of the objects filtered through colour lenses; shifting shades of yellow, green, blue, purple, and pink simulate a volatile chemical reaction.

Each section of the three-panel divider has been dyed using plants plucked from the artist's garden in Tangier, Morocco: red from the rusted colour of madder root, pink from avocado pips and skins, and cosmic yellow hues from turmeric root and chamomile.

Barrada's interplay with film and form echoes what Accardi told curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2002: that her sculptures are driven by a desire to expose the vitality beyond the surface of three-dimensional shapes. 'I wanted to be a contemporary artist, I wanted to find out what "contemporary" meant,' she explained.1

With that in mind, each artist in this show holds their definition of what it means to be 'contemporary' and make work in a modern way—notably, by emphasising the material and formal qualities of the art object through dynamic experimentation.

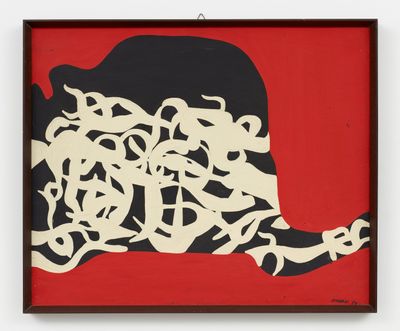

Among them, the eminent Lebanese painter and sculptor Saloua Raouda Choucair, widely considered 'one of the first abstract modernist painters in Lebanon and possibly the Arab world', is represented by 21 works spread across all three rooms at Pace Gallery.2

Choucair lived in Paris from 1948 to 1952, where she studied under Fernand Léger. A portion of the exhibition is dedicated to paintings Choucair made during and after this formative period.

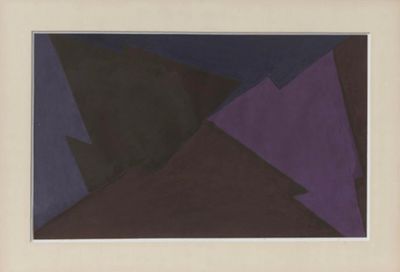

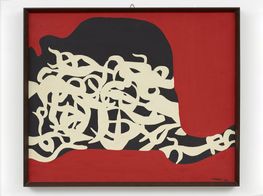

Dark blue, purple, and black geometric shapes make up Module (1947), which contrast with exuberant orange and green forms over clean negative space in Experiment with Calligraphy (Blue) (1949).

Choucair's paintings are punctuated by two small-scale wooden sculptures and three miniature brass and bronze forms. Wood Dual Round (1975–1977) has been carved out to create two interlocking limbs that form a crevasse at the centre, while Spiral Rhythm (1985–1987), made ten years later, builds its curve like a wooden vertebra.

It's impressive to see how these works function in relative harmony with the others on view, as hierarchies collapse to open the terrain for a more sophisticated understanding of modernism.

Choucair carves out spaces between each block to show their interdependence, modelled after the undulating forms of organic geometries, with incisions and subtle spaces attesting to the artist's literary influences.

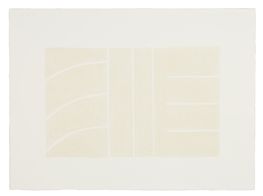

Referring to her work as 'sculptural poems', Choucair assimilated the structural instincts of Arabic poetry, with a formal verticality that functions like poetic feet stretching across the page, flowing from top to bottom. Thin lines in the monolithic Poem (1972–1974) mark the surface of the brass prism, while Poem (Ramlet el Beida) (1966/2013) mimics enjambed lines in bronze.

Choucair's sculptures are nestled between five by Barbara Hepworth in the next room, each typical of Hepworth's oeuvre. Disc with strings (Sun) (1969) imbues a bronze circle with strings arranged like rays of light, while the edges of the brass metal curve in Stringed figure (Curlew) (Maquette I) (1956) are perforated with holes to host a threading of cord that creates a radiating lines across each side.

Hepworth's sculptures engage with the material concerns of Singaporean-British artist Kim Lim's River Run II (1996–1997), in which carvings on a rectangular slab of marble balanced on a long wooden block reflect the upward motion of a river tide.

Echoing the flow of Lim's river are the jagged alabaster objects of Hepworth's Two Forms (1934)—respectively vertical, horizontal, and round—their smooth surfaces akin to mineral erosion by water.

Born in Singapore in 1936, Lim moved to the U.K. in 1954 at the age of 18 to study at London's Saint Martin's School of Art and Slade School of Fine Art, developing a sculptural practice with an emphasis on contrasting material qualities and 'the tension between forms'.

The interlocking aluminium spikes of Lim's Plus I, Plus II, and Plus III (all 1966), featured in this show, were created 11 years before Lim exhibited at the 1977 Hayward Annual (25 May–4 July 1977) as the only non-white and female artist. They are an important precursor to how Lim engaged with material and form to direct attention to negative space.

It feels significant that Choucair's and Lim's works are present within all three rooms of the exhibition, while sculptures by Hepworth—who was opposed to participating in 'all-women' shows and more interested in exhibitions that drew works from all over the world—are solely within this small enclosure, thus upsetting Hepworth's position at the centre of 'modernism' by expanding the movement's geographical purview.

Both Choucair and Lim have received growing recognition for their contributions to modernist sculpture in recent decades, with shows at major institutions like Tate acknowledging their place in an ever-expanding canon.

Compared to the current display of German women painters at London's Royal Academy of Arts, Making Modernism (12 November 2022–12 February 2023), Creating Abstraction diverts from the narrative of 'modernism' as a Eurocentric phenomenon.

But the challenge is equally temporal. Works by Barrada and fellow contemporary artist Leonor Antunes are seamlessly placed alongside historical works, suggesting the curatorial interpretation of modernism as a movement that extends beyond the early 20th century.

Here is where the exhibition title functions best. Creating Abstraction, which narrowly avoids the conflation of modernism and abstraction by declaring the latter as an offshoot of the former, still upholds the concept of modernism as a movement rooted in material characteristics. But the exhibition also draws attention to the material processes by which non-representative forms take shape.3

Among the most resourceful is Louise Nevelson, who was born in the Russian Empire's Poltava Governorate (modern-day Ukraine), whose work is inextricably linked to her life in New York City, where she lived until her death in 1988.

The 83 elements that make up Nevelson's Untitled (1971) include unwanted objects found on the streets outside Nevelson's studio. Gilded by a new sheen of context, blackened cubes filled with matter are stacked into a lofty tower, with 12 layers in rows of sevenfrom the floor up.

It's impressive to see how these works function in relative harmony with the others on view, as hierarchies collapse to open the terrain for a more sophisticated understanding of modernism. —[O]

1 Carla Accardi, 'Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist Carla Accardi: To Dig Deep' (trans. by Beatrice Barbareschi), Flash Art (May 2008): p. 96-99.

2 Lamia Rustum Shehadeh, Women and War in Lebanon (University Press of Florida: Florida, 1999).

3 Saskia Flower, 'Creating Abstraction: The Materiality of Modernism', Pace Gallery, 29 January 2022, https://www.pacegallery.com/journal/creating-abstraction-materiality-modernism/.