Kamala Ibrahim Ishag’s Fluid, Untethered Modernism

Kamala Ibrahim Ishag (2019). Photo: Prince Claus Fund.

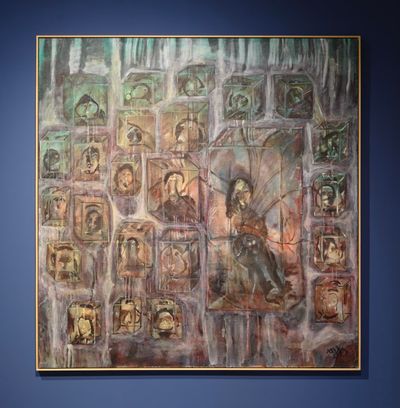

In 2022, the Sudanese artist Kamala Ibrahim Ishag filled a large, blue-primed canvas, measuring around two-by-three metres, with grey orbs containing round faces, each one connected by leafy vines snaking over the image in curving, vertical lines.

Titled Blues for the Martyrs, the painting responds to the events of 3 June 2019, when soldiers fired at pro-democracy demonstrators performing a sit-in outside the Sudanese military's headquarters in Khartoum, killing hundreds. This peaceful civilian protest called for a civilian government to replace the military council that had been established after a popular uprising forced President Omar al-Bashir's resignation that April.

While a committee was established by former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok to investigate that bloody June day, it has been plagued with accusations of misconduct. Then in March 2022, Sudanese forces raided the commission's offices, forcing a suspension of operations.

Amid this backdrop, Ishag's image is one of defiance and hope, in which bodies are depicted inside cellular forms, like eggs fertilising on an infinite, ever-flowing river—a commemoration of the bodies that were apparently thrown into the Nile during and as a result of the 3 June massacre. Its message, conveyed through symbolic abstraction, heralds the continuity of what was started.

Born in 1939 in Bait al-Mal, a quarter of Omdurman, Sudan's most populous city, Ishag has long deployed the brush to confront to political injustices and asymmetries. As a student at the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum, she was one of the first women artists to graduate from there when she completed her studies in 1963.

After studying at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London from 1964 to 1966, and again from 1968 to 1969, Ishag returned to Sudan to teach at the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum. She became associated with the Khartoum School, known for its fusion of Arab and African traditions to create a unique modernist aesthetic that was closely tied to the articulation of an independent Sudanese national identity.

Ishag would eventually break away from the Khartoum School to establish the Crystalist Group around 1973, alongside two of her students, Muhammad Hamid Shaddad and Nayla El Tayib. In 1976, the group published 'The Crystalist Manifesto' in a Khartoum newspaper, which articulated a radically fluid position that resisted the patriarchal braiding of nationalism and modernism that defined the Khartoum School.

Advocating for an expansive prism of creative and boundless possibility, the manifesto, worth reading in its entirety, is grounded in concrete politics. 'The basic premise for Crystalist thought, or modern liberalism, is to reject the essential quality of things,' the text states.1

Referring to the atom and the discovery of smaller units within it, the Crystalist position acknowledges a world in constant process of fractal discovery. 'The Cosmos' is likened to 'a transparent crystal with no veil and eternal depth', where many truths can be held at once; such that whatever is infinite may be finite, too, and delineation need not be synonymised with division.

The Crystalist Manifesto, in short, is an invitation to open up rather than close off. 'We are living a new life, and this life needs a new language and new poetry,' the text proclaims. These ideas not only infuse Ishag's imagery, where fluid strokes build up figures suspended between solid and fluid form, but defined her teaching as a professor at the School of Art in Khartoum for some three decades, and her impact on future generations.

'Her defiance has opened up a world of possibilities for generations of artists, an impact that I had the fortune of witnessing while spending time with her in Khartoum several years ago,' notes Hoor Al Qasimi, the founding director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, who has co-curated Ishag's first solo exhibition in the U.K. at London's Serpentine Galleries (7 October 2022–29 January 2023), alongside Africa Institute Director Salah M. Hassan and Serpentine curators Melissa Blanchflower and Sarah Hamed.

The exhibition, which builds on a 2016 show staged at the Sharjah Art Foundation, encompasses 60 years of art-making, with large-scale oil paintings, works on paper, and painted objects including calabashes, leather drums, and a painted wooden partition, all testifying to Ishag's prolific practice.

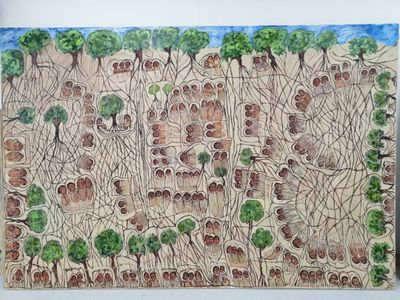

The depiction of organic networks, an utterly unique interrogation of the grid, is a hallmark of Ishag's unique painting style. In 2019, she rendered Bait Al-Mal, the place where she was born and grew up, into an organic network of bodies swaddled in white striped cocoons, each unit connecting with sinuous lines that in turn connect with trees that complete a symbolic mapping.

Defined by an earthly palette of creams, browns, and greens, the painting was first shown in the Lahore Biennale in Pakistan in 2019, and is likewise included in Ishag's Serpentine show, which illuminates the throughlines defining a career that extends over half a century.

Here, spirituality and nature, rather than nationalism and identity, encapsulate practices seeking to convey a world beyond words.

'It has been fascinating to identify the threads that have flowed through [Ishag's] work across her career namely, states of oneness—the interconnections between nature and people,' notes Melissa Blanchflower. 'What we hope will be interesting is for viewers to see the connections between these paintings and large-scale plant works, which show foliage and leaves within floating spheres.'

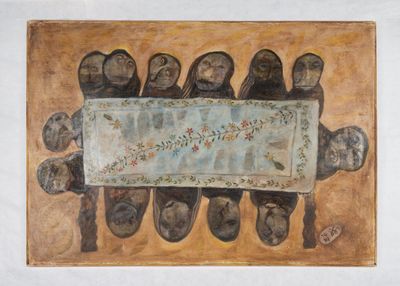

Among the works on view are early paintings created during Ishag's Crystalist period, which portray women encased within transparent cubes, as with Women in Crystal Cubes from 1984. A large canvas is covered in a tempestuous wash of forest green and rust tones, amplifying the sense of melancholic isolation that infuses the three-dimensional cubes that cover the image plane. Each contains a shadowy face; they surround a larger entombment just off-centre, to which all shapes are connected with dark veins.

The work is a stark contrast to a 2015 painting, Women in Cubes, which was included in Women in Crystal Cubes, Ishag's first solo exhibition in the Netherlands at the Prince Claus Fund Gallery, Amsterdam, which opened the year she received the 2019 Principal Prince Claus Award.

In this painting, the creams, browns, and greens of Bait Al-Mal return, with women in white robes connected by chains of leaves and flowers, forming a circle around an plume of leaves shaped into an egg. The painting visually connects to the artist's distinctive 'Zar' paintings, which reflect Ishag's field research into ceremonies of ritual healing from spirit possession conducted mainly on women.

Ishag's 'Zar' compositions draw from Sudan's colours and forms as much as the consolidation of art and spirituality in the work of William Blake, whose work Ishag encountered as a student in London, where Zar ceremonies formed the basis for her RCA thesis and degree show. The resulting paintings translate ideas of transmutation into compositions that express a distinctive, organic formalism.

In the oil on canvas Procession (Zaar) (2015), a circle of calligraphic bodies crowned by a larger figure cloaked in white are robed in black strokes highlighted by glowing green, colourfield stains. Their bodies cast leaf-like halos and shadows in luminous washes of greens and browns over a sand-toned surface, and extend from the central ring to form a kaleidoscopic chorus that orbits the central swirl.

In the brown-scale canvas from 2016, The Seat – Zar Ceremony, two figures are seated at both sides of a table bearing a vessel exuding incense smoke. Their faces are doubled up with the second stretching up from the main, as if to visualise the invocation of another dimension that extends from within each body.

The depiction of organic networks is a hallmark of Ishag's unique painting style.

This multi-dimensionality, a formalism that is untethered and unbound, extends across Ishag's paintings. That expansive dynamism defines her latest survey: an eye-opening pathway into global modernism that bridges the 20th and 21st centuries.

'It feels like the perfect moment to introduce new audiences to Kamala's work, which is just as innovative now as it was 60 years ago,' says Al Qasimi. 'Looking at the bigger picture, at a time when the art world is undergoing a collective reassessment of a canon that has long been for the most part white, Western and male, this exhibition is one attempt at offering a more inclusive, global narrative.'

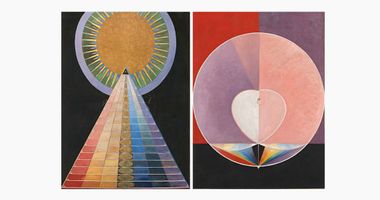

From within that expanding narrative emerges an art-historical trajectory that finds resonances between Ishag's paintings and the likes of Hilma af Klint. Here, spirituality and nature, rather than nationalism and identity, encapsulate practices seeking to convey a world beyond words through formal languages that invite a contemplative, open-minded presence. —[O]

1 Hassan Abdallah, Naiyla Al Tayib, Hashim Ibrahim, Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, and Muhammad Hamid Shaddad, 'Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents – The Crystalist Manifesto', post – notes on art in a global context, MoMA, 4 April 2018, https://post.moma.org/modern-art-in-the-arab-world-primary-documents-the-crystalist-manifesto/.