At Thailand Biennale, Uneven Connections Abound

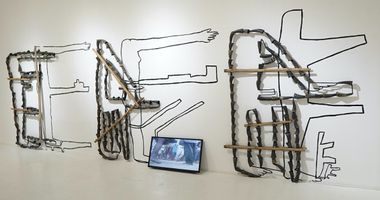

Yang Fudong, The Bitterly Silent Nights I Hate (2021). Site-specific installation, 7-channel video, sound. Duration 20 min, 50 sec. Exhibition view: Thailand Biennale, Korat (18 December 2021–31 March 2022). Commission. Courtesy Thailand Biennale, Korat.

Launched three years after its inaugural edition in Krabi in 2018, the Thailand Biennale's second edition has moved to Korat, the capital city of Nakhon Ratchasima Province in the landlocked region of Isan.

As a state-funded organisation, the Biennale's nomadism is managed by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture and the Ministry of Culture, and aims to support Thailand's contemporary art scenes beyond the capital of Bangkok while fostering local economies through cultural tourism.

Conceived by artistic director Yuko Hasegawa with co-curators Seiha Kurosawa, Vipash Purichanont, and Tawatchai Somkong, Butterflies Frolicking on the Mud: Engendering Sensible Capital (18 December 2021–31 March 2022) references 'social common capital'1 coined by Japanese economist and environmental activist Hirofumi Uzawa, which calls for an eco-sensitive and community-minded economic system.

But while these themes are timely—the main title refers to the incredible fact that butterflies have repopulated the Isan region due to the decrease in human activity during the pandemic—the show suffers from a lack of coherence and logistical issues worsened by Covid.

Some of the 53 artists and art collectives from 25 different countries participating were compelled to redesign their initial project and work remotely. As was the case for Yllang Montenegro's Skinship (2021), an installation of interconnected aprons with plants addressing the challenge of reciprocal care and social distancing during the ongoing pandemic.

While others like Olafur Eliasson—whose sound installation More-than-human songs (2021) broadcasts local birdsong interpreted by human bird imitators in six villages of the province—were installed just in time for the Biennale's inauguration, which has been postponed several times over the last 18 months.

The dramatic location of Phimai, an ancient city of the Khmer Empire located 60 kilometres away from Korat, makes up for a lot of the issues. At the Phimai National Museum, works by nine contemporary artists engage in dialogue with ancient artefacts mostly sourced from the lower northeastern region of Isan.

Nature's Breath: Arokhayasala (1995), an iconic installation by Thai avantgarde master Montien Boonma, holds court in the museum's main gallery. Rectangular metal cases are piled on top of each other to form a corbel arch, recalling the distinctive design of Khmer stone architecture.

The installation's brownish tones and rusted textures fuse harmoniously with surrounding ancient stone sculptures, while the openwork boxes containing dried fragrant herbs create associations with Thai traditional medicine.

The name of the work, Arokhayasala, refers to the infirmaries of the Khmer Empire commonly found throughout the lower Isan region, and a metal lung hangs in the middle of the installation like a votive offering.

Sharing the room is Waves (2021), installed by Federico Herrero remotely from Costa Rica. Vivid blocks of colour have been applied on the gallery's walls in overlapping curved shapes, their forms extended by half-painted platforms of concrete placed inside and outside the museum.

A comparable enlivenment takes place in Memories in Light (2021), a site-specific light and sound installation created for the rectangular pavilion normally used as museum storage, by architect Tsuyoshi Tane.

Isolated by black curtains, the formerly open storage takes on the solemnity of a temple. Transmitted through speakers amid displays of mostly Khmer artefacts is the sound of a male voice chanting Buddhist sutras.

Ambulating between various antiquities, viewers are hit with lights flashing from a set of moving lamps hanging from the building's frame. Moving up and down like fishing rods, the lights do not illuminate the space so much as act like its defibrillator, their electric pulses seemingly resurrecting the souls of creatures contained in the iconographies on each artefact.

Sound and movement also charge Yang Fudong's video installation The Bitterly Silent Nights I Hate (2021), projected on seven screens fixed on the floors and walls of the museum's auditorium in an irregular circle.

Scenes from Shanghai, Korat, and Phimai are interlaced, with three Thai school girls acting as guides through an audiovisual palimpsest. Colours and streets are grey in Shanghai, whereas views of the Nakhon Ratchasima countryside are colourful and full of life. Tying it all together is the legend of Pachit-Orapim, a local folktale about the origin of the name 'Phimai', which anchors sequences in the ancient city.

But while a balanced curatorial unfolds at Phimai, the central exhibition in the city of Korat is surprisingly irregular. Showing works at the Korat Zoo, for example, feels like a great idea; presumably based on the Biennale's call for an equitable existence between humans and non-humans. But given the zoo's instrumentalisation of animal life for entertainment, artistic interventions could have been sharper.

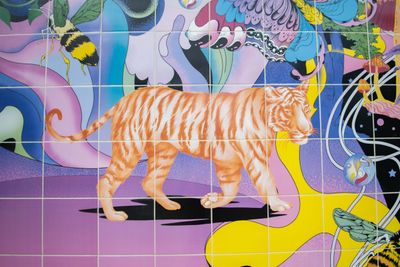

The Art of Wonder (2021), a ten-metre-wide mural made from digitally printed ceramic tiles by Thai artist and illustrator Pomme Chan, epitomises the issue. Rendered as graphic illustrations, mammals, insects, and flora—among them tigers, butterflies, and mushrooms—represent the biodiversity of the Korat plateau.

Created as a permanent installation in the zoo's waterpark, where dinosaur replicas are arranged, the work's colourful palette and style do not match the urgency of the discourse surrounding ecological crisis, even if the gesture might be directed at younger viewers. Its 'Augmented Reality' extension brings the piece closer to pure distraction.

...the main title refers to the incredible fact that butterflies have repopulated the Isan region due to the decrease in human activity during the pandemic.

More effective are installations like Rice Tower (2020–2021), a nine-metre-high wood structure inspired by local rice barns by Boonserm Premthada, and Bianca Bondi's isolated bedroom decorated by copper objects partly covered in salt, The Antechambre (Thai Crane) (2021).

But while convincing as artworks, they do not connect with their surroundings, nor each other, despite their proximity. Take Bondi's so-called site-specific installation, which is in fact an adaptation of a previous work created for the Busan Biennale 2020.

Making up for these disconnections to site are two commissioned outdoor installations in Korat city centre, which are expected to remain in place after the exhibition ends. Each one is an effective response to the urban landscape.

Sandra Cinto's 17-metre-long blue pavement at Thao Suranari Memorial Park, Korat city's greatest landmark, forms a promenade in The Wishes Boulevard (2021), with white drawings printed on blue ceramic tiles, each one made and signed by local children who depicted their visions of the future.

About 300 metres away, Perimetrava Nail Salon (2021) by Assume Vivid Astro Focus invites skaters to use skate ramps decorated like giant colourfully varnished nails, challenging the male-centricity of skateboard culture.

Located in a very different environment is Sim Isan (2021), another commissioned work for public space created by Thai artists Alongkorn Lauwatthana and Homesawan Umansap. A trapezoid ziggurat-like structure has been built around a real tree along the lake in Bung Ta Lua Park, more than six kilometres south from the Korat city centre. Its surface is painted with colourful animalistic motifs.

Yet within one of the greenest and most tranquil places in Korat, the work feels at odds with its surroundings and the tree seems to suffer from a lack of light and space.

That sense of distance and disconnection echoes the experience of this Biennale, which feels like an exercise in advanced orienteering with limited transportation options to reach remote locations, and a lack of signage or available on-site information. All of this has impacted local enthusiasm and attendance.

In a possible attempt to remedy this lack and perhaps rectify the delayed arrival of some works, the Biennale has launched 'Phase 2' on 15 January 2022 at the Rajamangala University of Technology Isan and the Thai Crane Research Centre in the Korat Zoo. But what works are showing is still TBD.

On a positive note, an emphasis on commissioning site-specific permanent works is an appropriate move to balance the Biennale's ephemeral nature, and while nascent, the event has attracted talented artists and renowned curators so far. The next step is to tackle problems of deployment and implementation.—[O]

1. Uzawa, Hirofumi (2005). Economic Analysis of Social Common Capital. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.