Tokyo: Autumn Exhibitions to See

Recycled paper, staple, acrylic, wood; I Don’t Have a Dog. I Don’t Have a Gun. I’ll Have Your 30min. Sorry!, 2012. Felt, wood, wheel, carbon frame. Photo: Jun Jiwon. Courtesy The National Art Center, Tokyo

Seventy years after the end of the Second World War, three major Japanese Art institutions in Tokyo explore both modern history and present day Japan.

Seventy years after the end of the Second World War, this autumn three major institutions in Tokyo explore both modern history and present day Japan. The National Art Center and Mori Art Museum, through two very different shows, examine Japan’s relationships with neighbouring Korea and Vietnam, while MOMAT focuses on Japanese photography from the ‘70s that changed not only perceptions of the country but also the medium of photography itself, focusing on a generation of artists adamant of the need to reexamine ideas of borders and boundaries in the context of a shared and uncertain future.

Artist File 2015 Next Doors: Contemporary Art in Japan and Korea

The National Art Center, Tokyo

29 July to 12 October, 2015

The importance of the solo show format is a prominent feature of the Artist File series which, since 2008, has each year focused on upcoming artists within the context of museum curation. Held at the National Art Center, Tokyo, the latest edition is subtitled Next Doors: Contemporary Art in Japan and Korea, and the geographic relationship between both countries is emphasised with 2015 marking 50 years of diplomatic relations between both countries.Six Korean and Six Japanese artists are represented: Im Heungsoon, Ki Seulki, Kobayashi Kohei, Lee Hyein, Lee Sungmi, Lee Wonho, Minamikawa Shimon, Momose Aya, Tezuka Aiko, Tomii Motohiro, Yang Junguk and Yokomizo Shizuka. Placing no real significance on age or medium, the exhibition aims to slowly draw in the audience with a distinct selection of contemporary art that reinforces the countries complicated relationship.

Much of the video work shown in the show delicately explores the line between what constitutes fact and fiction, situating fictional narratives amongst very real events. Im Heungsoon’s Jeju Prayer (2012) is an experimental documentary set on the southern Korean Island of Jeju recalling testimony of the Jeju Uprising where on 3 April, 1948 protestors fought with the South Korean army. Characters move back and forth between the past and present, attempting to understand an event through Im’s extremely personal filmmaking.

Yang Junguk, Fatigue is always with the dream, 2013. Wood, motor, thread. Photo: Kim NamheeIn Phantom (2006–2015), Yokomizo Shizuka places five photographs opposite five videos. In each video a person describes a chance paranormal experience. All of this is inexplicit, and you're left wondering who these people are, and whether their stories are true or not. Momose Aya’s film piece, Fixed Point Observation (With a Friend from a Camp) (2015), features an off-duty member of Japan’s self-defence force reading aloud his response to Momose’s prepared questionnaire. With his back to the camera, sitting at the counter of some empty bar, it’s uncertain whether his answers are his or someone else’s.

Lee Hyein paints in and around Berlin, each day spent painting from the protection of a tent that is shown here in recreation: The Tools of a Suspicious Camper (2015). In an accompanying video Lee recounts, while scrawling on a lamppost, how a mand she unwittingly filmed once threatened her. Having travelled from Goyang City in Korea to Germany, the paintings of The Second Life (2013) and installation I Don't Have a Dog. I Don't Have a Gun. I’ll Have Your 30 Minutes. Sorry! (2013) describe the desire to explore—despite threats—with a sense of the relief and freedom found in the strange unknown climate of a foreign country.

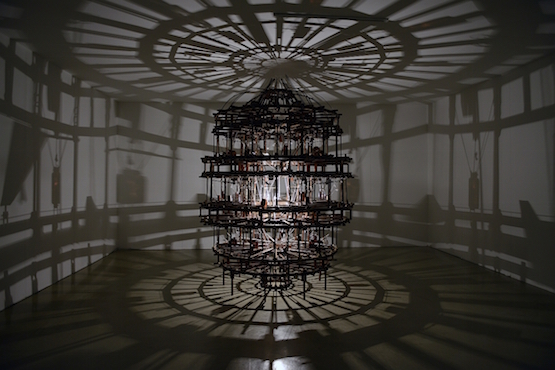

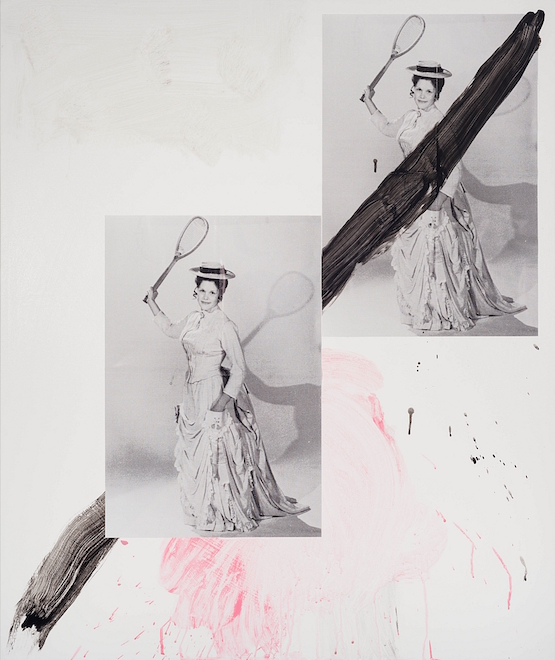

Minamikawa Shimon’s work spans almost the entire length of the gallery, pointing at ideas of implied geography and implied meaning. There are references to Minamikawa’s time in Berlin and Paris, a repetition of image and ideas of originality and authorship. The double image of Play (2014) adds a swift brush mark to one image that oversells another, whereas Four paintings, two legs (2013) and Four paintings, no legs (2013) play with the use of colour, framing and display. Their position is temporary and flexible, an argument that knowledge and application are prone to sudden changes dependent on time, place, and circumstance, qualities which reflect the work of all the artists on show.

Minamikawa Shimon, Play, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, paper collage Courtesy: MISAKO&ROSENThe Japan/Korea treaty took 14 years to materialise. This year’s anniversary was marked in unique style, with both leaders choosing to hold their own parallel ceremonies instead of meeting publicly— their common goal of cooperation still anchored to the past somewhat. In contrast, the work of Artist File 2015 looks for others ways to translate past experience into more meaningful methods of production—moving beyond the past, by observing and commenting on the present.

Dinh Q. Lê: Memory for Tomorrow

Mori Art Museum

25 July to 12 October, 2015

Memory for Tomorrow follows Vietnamese-born Dinh Q. Lê through experiences of the Vietnam War collected from interviews and information entrusted to him by survivors and wartime artists. The exhibition makes for a succinct statement, as relevant today as it was 40 years ago when the Vietnam War drew to a close, and a new period of doubt and secrecy began.Migrating to America as a child and returning to Vietnam in 1997, the retrospective at Mori Art Museum is the artist’s first solo museum show in Asia. He has yet to show his work in Vietnam. Given the artist’s international acclaim, it’s an indication that any attention gained abroad remains in sharp contrast to acceptance at home, likely to be partially attributed to his work openly questioning the 'official' version of Vietnam social history as promoted by the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam.

Dinh Q. Lê, The Farmers and the Helicopters, 2006. 3-channel color video with sound, handcrafted full-size helicopter. 250 × 1,070 × 350 cm; 15 min. Collaborating Artists: Tran Quoc Hai, Le Van Danh, Phu-Nam Thuc Ha, Tuan Andrew Nguyen. Commissioned by Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Australia. Exhibition view: “Dinh Q. Lê: Memory for Tomorrow,” Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2015. Photo: Nagare Satoshi. Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, TokyoThe exhibition addresses the contradictions between how we perceive conflict and how its particular motifs continue to reverberate throughout contemporary culture. The work, The Farmers and the Helicopters (2006), for example, consists of a life-size helicopter, and an accompanying video which shows both the artist’s attempts to build the helicopter alongside images of the destruction that similar machines have waged from the sky.

Another issue raised by the show is the premise that a foreign understanding of the Vietnam War is almost entirely based on a foreign perspective. Films such as Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) describe the experience of war through the Hollywood lens, with soldiers either returning to US soil marked with hostility and indifference, or descending into perennial worlds of torment and confusion. Dinh Q. Lê’s continuing ‘Photo weaving’ series and Untitled (Paramount) (2003) are reminders of how Vietnamese and American perspectives continue to be at odds with each other. In Light and Belief: Sketches of Life form the Vietnam War (2012), which was originally shown at dOCUMENTA (13), the artist explores a different viewpoint from that of Hollywood presenting 100 drawings by former Vietnamese War artists recalling their youth spent during wartime.

Dinh Q. Lê, Light and Belief: Sketches of Life from the Vietnam War, 2012. 100 drawings: pencil, watercolor, ink, and oil on paper / single-channel color video with sound. Dimensions variable; 35 min. Collection: Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, The Henry L. Hillman Fund, 2013.37.1-102. Exhibition view: “Dinh Q. Lê: Memory for Tomorrow,” Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2015. Photo: Nagare Satoshi. Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, TokyoIn the context of Japan, Everything is a Re-Enactment (2015) is an awkward reminder of the past, with an array of military uniforms from Vietnam, China and Japan standing side by side. An accompanying video follows a young Japanese man and war enthusiast at home in his dressing room surrounded by his collection of uniforms from the Second World War onwards. He makes the point that the ‘re-enactment’ of wearing his collection is not nostalgic but a yearning desire for an authority absent in his everyday working life. He’s not old enough to remember the war. Even still, the symbolism these uniforms possess is not lost on him. He chooses to only wear them from the sanctuary and seclusion of his home.

Dinh Q. Lê, Everything Is a Re-Enactment, 2015. Single-channel color video with sound, military uniforms 26 min. Commissioned by the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2015In Vietnam, there are few formal reminders of the wartime period. The government is careful to limit what is reported, at times even banning its mention. It is one reason Dinh Q. Lê is yet to show his work in his own country. With each passing decade survivors who Dinh Q. Lê has met gradually pass away and along with them their memories of the war. The biggest sentiment the exhibition makes is the persistence of memory. Dinh Q. Lê is adamant that beyond documenting Vietnam’s past for his own benefit, the way it is remembered partially or in fragments guides others to understand and appreciate the consequences of such conflict, be it in the past, present, future, or elsewhere.

THINGS Rethinking Japanese Photography and Art in the 1970s

MOMAT (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

26 May to 13 September, 2015

Things that occur beyond the camera lens became an important concept for Japanese photography in the ‘70s. In exploring varied subjects from conflicts of place to the human figure, many Japanese photographers such as Nakahira Takuma became dissatisfied with the aesthetics of the day and focused on the relationship between things—they explored the in-between spaces that are often fraught and often at odds with the tangible world when seen in isolation, bereft of people or other signs of life.Exhibition view, Things | Rethinking Japanese Photography and Art in the 1970s, MOMAT (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2015. Photo: Otani IchiroSplit in to five distinguishable sections—‘Encounters with Things’, ‘Atget and Evans’, ‘Cities and Villages’, ‘Experiments and Duels’, and ‘Things, Simple Substances and Omens'—the exhibition follows Nakahira in search of the modern world as a rapidly developing object, as he understood it, tracing pivotal moments of artistic and social history throughout that decade.

Work is also attributed to other like-minded photographers, artists and sculptors not only Japanese but all of who became connected with faithful representations of the world, and a physical perspective that registered and wrestled with the substance of both the city and nature (Jikken Kobo: Experimental Workshop), sense and nonsense (Takamatsu Jiro’s Oneness), and a conceptual artistic approach in swift contradiction to the sterile space of a traditional gallery (Akasegawa Genpei’s Hyper Art Thomasson).

Takanashi Yutaka, Hongo: Usagiya Store, 4-35-4 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku from Machi, 1975. Image courtesy MOMAT, TokyoIn addition Ohtsuji Kiyoshi’s images of German artist Reiner Ruthenbeck, and Welsh sculptor Barry Flanagan at the 10th Tokyo Biennale: Between Matter and Man which took place at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in Ueno in 1970, are also included in the exhibition. Poised standing beside their work, the artists appear lost in the biennale space, the photographs seeming to express the material struggle between people and the physical world.

Work by Eugène Atget and Walker Evans also appears in the exhibition. This inclusion is interesting as it demonstrates how informed and affected by the work of others Nakahira and his contemporaries were. Atget’s cityscapes, were considered by surrealists in early 20th century Paris to be unconscious documents of that age. Nakahira also mentioned them as being marked with “a gaze of the city.” Atget was a flâneur who captured things as encountered on back streets, focusing on their inherent absence. Evans’ observation of depression-era America came with its own form of quiet and measured melancholia and images that represent a period that marked American poverty in the ‘20s and ‘30s.

Nakahira was interested in photography that confronts “things head-on and captures (things) matter-of-factly.” It’s an approach best encapsulated in the book Duel on Photography (1977) coupling his writing with photographs by Shinoyama Kishin. Kishin, he states, does not “in any way attempt to privatise things or reality … Privatisation means blotting things out with your own emotions … countering the meanings that we usually give to reality and endowing it with your own private meanings. Kishin rejects this type of privatisation.” For Nakahira there is no soft-focus, only blunt truth and honesty.

Eugène Atget, Rag Pickers' Hut from 20 Photographs by Eugène Atget, 1912. Image courtesy MOMAT, TokyoThe show is limited in scale and barely scratches at the influence the ‘70s had on domestic and foreign artists. The show literally runs out of space, perhaps even time. Yet, exploring the consequence of those early experiments and how they have informed much of today’s photography would only really serve to further compound the importance of that decade; the politics, the protest, the relation between ‘subject’ and ‘object’, between the human body and the world, and the parallel worlds that gave Japanese photography a mutability all its own and turned it into a universally accepted art form.

On 1 September this year Nakahira died of Pneumonia at hospital in Yokohama aged 77. He remained an illusive figure throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. Soon after the publication of Duel on Photography (1977) he succumbed to illness, suffering acute memory loss and an impaired ability to speak as a result.

Following his recovery, and the publication of Adieu à X (1989) which earned him the Society of Photography Award in 1990, Yokohama Museum of Art held a major retrospective of his work entitled Nakahira Takuma: Degree Zero – Yokohama (2003). His lasting legacy is not limited to photography but extends beyond his essayed reasoning, actions and intent, influencing artists like Hatakeyama Naoya who follow Nakahira’s principle that photography “needs to stop expressing feelings. When it is completely a record, it can be something.”—[O]