Hiroshi Senju: No Need for Walls

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH GILLMAN BARRACKS

Looking at one of Hiroshi Senju's waterfall paintings feels akin to being alone inside a dark cave with a private cascade. They are not Niagara, Yosemite or Victoria; Hiroshi Senju's intimate waterfalls descend in pairs, trios or many columns of water, conveying a gentle rush. Mist emanates as water droplets (in reality, splashes of translucent paint) seem to spray up from the foamy bottom of the streams.

Hiroshi Senju, Waterfall (Blue) (2010). Acrylic pigment on mulberry paper mounted on board. 117 × 117 cm. Courtesy Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong/New York/Singapore.

These paintings of waterfalls (Heraclitian symbols of life, but also, over time, forces that can destroy something as seemingly permanent as rocks) conjure not only the appearance of rushing water, but also seem to evoke its sound, smell and feel.

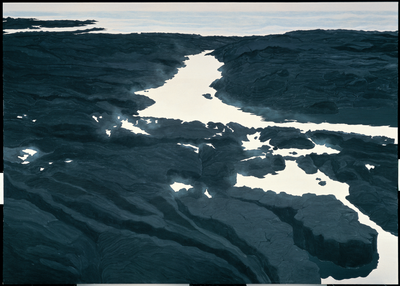

Using pigments made from minerals, stones, shells and corals mixed with animal-hide glue, Senju is one of few contemporary masters of nihonga, a Japanese school of painting based on traditional materials and styles. Widely recognised for his waterfalls and large-scale cliff paintings, Senju makes his works by pouring paint onto a delicate support of mulberry paper on board. It has been suggested that he is an alchemist, transforming pigments from the earth into water and air to investigate the poetics of the material world.

Senju rose to fame in the 1990s; in 1995, he represented Japan at the 46th Venice Biennale with a 14-metre-wide waterfall mural titled The Fall (1995), a reference to Adam and Eve's plunge from grace. Two decades later, in Venice again for the Biennale collateral event Frontiers Reimagined (9 May–22 November 2015), Senju exhibited large-scale fluorescent-pigment waterfalls Ryujin I and Ryujin II (both 2014) and a natural-pigment waterfall painting titled Suijin (2015).

In contrast to the regular practice of showing nihonga paintings in dimly lit rooms, Senju prefers that his are viewed in natural light; a point of consideration when architect Ryue Nishizawa designed the Hiroshi Senju Museum Karuizawa, which opened in central Japan in 2011. The museum houses paintings by Senju from 1978 to 2017, including early figurative works.

Senju is currently a professor of the Kyoto University of Art & Design, where he was president from 2007 to 2013; director of Koyodo Museum of Art, Nagano; and advisor of The Tokugawa Art Museum, Mito. From 2004 to 2011, as art director for renovations at Tokyo's Haneda Airport, Senju created a series of large commissioned works for the terminals. In 2017, he was announced as a recipient of the Isamu Noguchi Award, joining the ranks of previous winners such as the architects Tadao Ando, Norman Foster and Yoshio Taniguchi, and the artists Elyn Zimmerman and Hiroshi Sugimoto.

Your early paintings, such as A Far (1978), which depicts a woman sitting on a city wall, and When the Stardust Falls #10 (1994), an image of a deer in a nighttime landscape, are entirely figurative. Others such as Flatwater #4 (1993) are highly detailed landscapes. What led to your significant turn towards abstraction? At what moment did you realise you had come across a style that would continue throughout your career?

I have not thought of my image-making as figurative versus abstract. When I paint people and animals, I am not painting a specific image. On the other hand, for waterfall and cliffs, I have certain images in my mind. There is no boundary for me between figurative painting and abstract painting. I move back and forth freely.

My painted waterfalls are a combination of those that I have actually seen and those that I have imagined

You have said that in a masterpiece, you can 'hear the water flowing, smell the air, and even feel the temperature.' How do you actualise this multi-sensory experience in your paintings?

When you eat food, you experience it through multi-sensory means—temperature, texture, taste and sight. Fundamentally, art can be experienced with all your senses. Each sense has a strong relation to another. When you listen to music, you sometimes have a visual image in your mind. It is the same with the painting. Hot, cold, damp, dry; as an artist, you fully utilise all your senses and create works around these sensations.

There is an oscillation of place and scale in your waterfall paintings; they seem to be at once somewhere specific and entirely imagined. Are these waterfalls a place in your mind? Where do you go when you look at them?

Every day I experience waterfalls through the pouring of pigment on paper. This process helps me to understand more about the natural phenomenon. Sometimes I think of a particular image that I have seen, sometimes I explore my own imagination. I have been to Brazil, the United States, Japan and China to search for waterfalls, but I cannot capture their essence in paintings merely by looking at them. My painted waterfalls are a combination of those that I have actually seen and those that I have imagined.

For the design of the Hiroshi Senju Museum Karuizawa, you collaborated with Ryue Nishizawa, a rather avant-garde architect. The museum is full of natural light, a condition you prefer for displaying your paintings. Why is this? What is your vision for the institution going forward?

Nature has always been treasured as it is found. Conventional museums are usually dark and closed, so that treasured artefacts are not stolen.

Museums also have a history of being used to display captured and stolen treasures from other cultures, as seen in institutions such as the British Museum in London and the State Heritage Museum in Saint Petersburg. But I believe that during my lifetime, the world will become a place where there is no need for walls, and where we trust each other. Therefore, the Karuizawa museum itself is a message to the 21st-century world of a world without borders.

Personally, I have been influenced by five different kinds of art from different historical periods

The natural pigments in your dark, monochromatic paintings allow for remarkable luminescence. Your 'Falling Color' series (2006), however, is made with highly saturated industrial pigments, which have been compared to the neon city lights. How do you reconcile the two sets of elements: the organic and the man-made? Why did you turn to manufactured pigments?

I have used natural pigments, natural glue and natural paper my entire career—in a way, like an artist in the Ice Age. If an artist from the Ice Age were transferred to a contemporary city and saw the neon lights, they too would be moved, whether it is an advertisement for a bar or a billboard for beer. I wanted to express that emotion. Because I have used natural materials all my life, I can find beauty in artificial, fluorescent pigments.

It's been said that your work bridges Eastern and Western sensibilities: for example, your waterfall paintings can be situated in the history of modern abstraction, as well as that of traditional Japanese painting.

Indeed, the Isamu Noguchi Award recognises designers, architects and artists who share its namesake's ideals, including innovation and exchange between the East and West. You've also said that you do not follow any particular culture, but rather a 'modern culture'. How has your interest in 'modern culture' informed your art?

The idea of 'modern culture' is one where people are influenced by multiple generations, multiple geographical regions and are accepting of diversity. They seek to create harmony with those that are different, in an effort to figure out who they are. I would like to contribute one sample to this 'modern culture', which has taken tens of thousands of years to create.

Personally, I have been influenced by five different kinds of art from different historical periods: cave paintings during the Ice Age, 11th-century Chinese art, 15th-century Italian art, 17th-century Japanese art and lastly, 19th-century French art.

From the beginning of my art career, I have not simply separated art along the lines of East and West. Over the last 10,000 years, humans have created multiple, diverse art forms. But at the same time, since we are all human, we have found things that we mutually understand, and this is how human history and culture have been formed.

Why would we divide human history simply to the East and the West? I find that impossible as an idea. Originally, at the time of the Ice Age, there was no East and West, and even when you think about what influenced Renaissance and Impressionist art, this is clearly connected with other parts of the world. Cultures are full of noise rather than a single, pure sound. They can hardly be separated from each other, and one contaminates the other, creating a new generation of ideas and realities.

How was your work impacted by your move from your long-time home of Tokyo to New York, where your studio is in a former power plant?

In 1990, I had just turned 30 and wanted to explore different cultures around the world. The internet was not yet widely available—there was no home page and no Twitter. I had to physically move to the centre of the art scene. If I were a young artist today, I might move to a deserted island or into the mountains to create works, and submit information through the internet. —[O]