Charlotte Verity: Painting as a Matter of Urgency

Karsten Schubert London | Sponsored Content

Charlotte Verity. Photo: Dan Fontanelli.

Charlotte Verity. Photo: Dan Fontanelli.

In the cycles of lockdown, London's green spaces have offered moments of respite from endless hours indoors. Details that may otherwise have been missed in the rush of everyday life pre-pandemic, have asserted themselves in the illusion of time being seemingly suspended.

It is a mode of seeing that requires an openness, painter Charlotte Verity explains, with visual offerings made available to receptive eyes. Over the last four decades, Verity's garden in Camberwell, London, has been the core subject of her paintings.

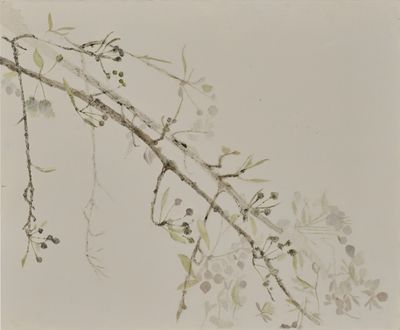

She has finetuned an intuitive response to subject matter within it, whether twigs, flowers, or leaves—their subtle forms painted through acute observation against serene planes of colour.

In their sparsity, her subjects have a humility, inviting viewers to question the transience of the natural world and to engage with a sense of wonder and open curiosity towards it.

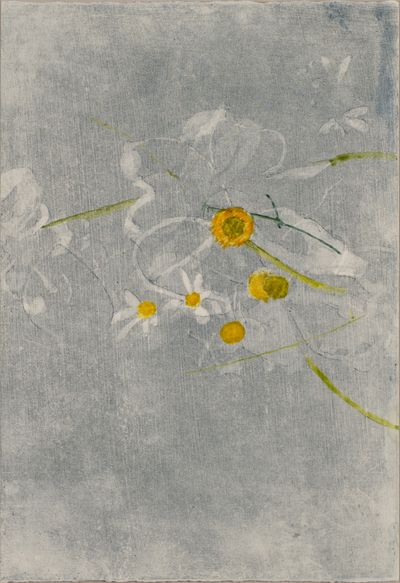

Verity's upcoming exhibition at Karsten Schubert London will be divided into two chapters: Echoing Green (16 July–15 August 2021) and Echoing Green Part II: The Printed Year (18 August–10 September 2021). The first exhibition features paintings, while the second presents the artist's first forays into the monotype process, which involves applying watercolour paint to a sheet of mylar, before it is pressed onto dampened paper. Both exhibitions will be viewable in Online Viewing Rooms on Ocula.

Through print, Verity found the means to capture an urgency of representation that defines her relationship to her subjects. Printing her images each fortnight, Verity tracked the year, finding different moments in the garden that spoke to wider shifts happening. 'When you spend time looking with this intensity, you notice the way time goes and the way things change—the speed of it', she explains. 'It wasn't just a study to track the changing of the seasons; it was almost a way of trying to say something about me in this world now.'

This receptiveness to her immediate surroundings allowed her to find subjects fitting to particular moments. A chaotic mass of stems in Love-in-a-Mist (2021) had an affinity to the 'scratchy, confused anxious stage of lockdown that summer', for instance, while Buds (2021)—a five-foot long painting of rose buds—speaks to the spring, and the 'surprise and wonder at really beautiful things arriving'.

In this conversation, Verity traces her practice, discussing the development of an ability to say more with less.

TMBetween 1950 and 1980, many British art schools dropped observational drawing as a practice, leaning towards a 20th-century modernist de-skilling. What was your experience of this at the Slade? Was this a practice that you developed after graduating?

CVI arrived at art school as an observational artist, but I was also really curious about the direction of contemporary art and wanted to have a dialogue with it.

Unusually for an art school in the mid-seventies, there was a small but strong element that was all about painting from what you see—a legacy of the Euston Road School. William Coldstream was still running the Slade at that point, so he was around and a respected figure, but of course, because we were students, we questioned everything.

Although the Slade was a small art school, they did employ forward-thinking artists, most of whom were successful and active in the contemporary art scene. And you are right, there was a strong element of de-skilling—or rather a profound questioning, as we saw it—of painting itself as a valid art form. Constructivism, Behaviourism, Colour Field Painting, and performance art were all strongly represented. Art history sessions had been replaced by seminars in anthropology.

As I'm painting these twigs and stems, I feel at one with their direction without quite knowing where they will end up on the canvas. I paint with a sense of curiosity, which leaves the painting in a state of open-endedness.

I was very torn, because the life room was an area of the school that was quiet and where I felt I could learn the skills I needed to become a good painter. But it was quite cut off from the other areas of the school, and engaging in the debates that were in the air weren't encouraged. I found that profoundly disappointing and difficult to navigate.

I realise now that I was lucky to have been allocated a tutor on a random basis called Noel Forster—a painter who was engaged with the fundamentals of painting, paring it right back to colour, performance, and touch.

So he was my tutor, and the good thing about that was that I had to justify the activity of sitting in front of something and trying to paint and draw it. The big question for me was how to make those paintings as central and meaningful and, in a way, cutting-edge, as the work that was going on in other areas of the school.

The other element that I think was really important at the time—although it was difficult at the time for me to synthesise all these things—was abstract painting. The influence of Colour Field painters from the States was prevalent and alluring and had another sort of rigour.

Their emphasis on the formal values of painting and making it as strong as it could be as an independent thing actually tallied with, say, Euan Uglow's ambition for painting, which was just that: to make a very strong work that had an independence in the world, after you'd left it. That formed my sense of what painting could achieve if I was sensitive to all the formal elements.

TMYou have been referred to as a botanical artist, and your work botanical art. This is of course a reductive description of your practice. Botanical art holds the purpose of describing plant life in a scientific, informative way. In relation to the early process of justifying your position, did that period provide a means to work through questions around that?

CVI explored abstract painting and certainly became engaged with the materiality of paint and the nature of the support. I justified working from the life model to myself as the equivalent of working in nature, but I soon realised that the subject dominated.

The human figure couldn't be reduced to patches of coloured paint; it wasn't just another part of nature. It has a sort of presence, and this sets a standard for any work of art.

You're right, this is the hinterland of why I see that what I do is a risk. I have found that painting and drawing directly from plant life leads me to make work that has feeling and presence, so being referred to as a botanical artist, which I am emphatically not, is a risk I am prepared to take. But each painting, drawing, or print has to make this clear and hold its own.

TMWas it always going to be nature as a subject for you?

CVOther than man-made things?

TMOr the urban environment, though that does sometimes come into your work in a very subtle way.

CVIt does, yes. It was just my bent really. As I say, I have tried other things, but I learnt that this is what makes me work with a very special kind of concentration. There is nothing trivial or time-bound about it. I look long and hard and it feels urgent. Every artist has to find something that totally sweeps them along.

TMYour early works encompass full, flat planes of colour, whereas your paintings today seem sparser, relying on the delicate structures of twigs, leaves, and flowers against paler backgrounds, which gives them a feeling of openness. What led you to this approach? Was it the result of dedicating time to observing, and becoming more attuned to creating more with less?

CVIf you think they've got that quality, then I'm very pleased. I remember I did a painting called Two Paths (1989) and it was just a twig I found in the street. I placed it on a slightly shiny, dark background. It was just the object and its shadow-cum-reflection. It was very simple and very dark.

I remember feeling that it was so important—urgent even—that I made this twig do exactly as it was doing and convey that sense of a path that I felt through painting it.

The fact that something so simple could put me in the mind of a path—or two paths, as in the famous poem 'The Road Not Taken' (1915) by Robert Frost—and at the same time resonate in an open area with no explanation of where it was, without a setting, felt enough. I had made a painting out of very little. In a way, I feel I've been doing that ever since.

It's obvious that having less distracting stuff gets you towards what you want. But to do that, amongst an abundance of choice, you have to be much clearer about the aim. You really have to finetune your ear to what your intuition is telling you.

As I'm painting these twigs and stems, I feel at one with their direction without quite knowing where they will end up on the canvas. I paint with a sense of curiosity, which leaves the painting in a state of open-endedness. Alice Oswald has said it better: 'The whole challenge of poetry is to keep language open, so that what we don't know can pass through it.'

You sort of have an idea of where you want to get to, but you don't know what's going to happen along the way. And that's the relationship that I like with the work. I don't want to dominate it too much.

TMOne feels that urgency in your monotypes. Would you say that these represent that urgency of representation, combined with an openness? And how did that tie into the last year in lockdown?

CVWell, the monotype plates have absolutely no resistance, so it encourages the swift mark, unlike previous watercolours, where there's a grain to the paper. It encourages an expressiveness somehow—a bit of abandon. I found it really hard to control.

I was committed to doing a series of watercolour monotypes at the beginning of 2020, which would track the year. The characteristics of the year, as it turned out—the combination of horror and fear and a strange quietude—enhanced this sense of urgency. The regularity of the days enabled me to fulfil my aim of making at least one plate a week, printing them every fortnight. There are around one hundred in total.

When you spend time looking with this intensity, you notice the way time goes and the way things change—the speed of it. And then this was broken down into what happened every week. It wasn't just a study to track the changing of the seasons; it was almost a way of trying to say something about me in this world now.

TMHow do you look for or happen upon subjects? Is it a conscious looking? Or do they represent overlapping moments of encounter?

CVThat is really complicated to answer, because it's so intuitive, but I'll try. Garden writer Vita Sackville-West has this lovely expression about what she does in the garden. She calls it prowling and peering—that act of walking stealthily in your garden, noticing something then drawing it closer to really look.

I might be in a garden or walking back from the shops, and something may catch my eye. If I'm not in a receptive mood, that may just vanish, but if you put yourself in a receptive mood, you make a note of it, somehow, in your mind. And then you try and find a form and colour that will give a similar sensation to what may have been just a glimpse.

Right through the year, I've found something that matched what was going on outside. For example, Love-in-a-mist (2021) has got lots of different lines—it's chaotic.

My garden is a fairly chaotic mass of stuff and flowers dying all over the place and seed heads forming. It seemed to match the scratchy, confused anxious stage of lockdown that summer. But during the spring, things felt different to me: there was a sense of surprise and wonder at really beautiful things arriving, which was made all the more powerful because there were various things going on in the family that chimed.

I think as an artist, you try and put everything into your work to give form to the expression of those different moments.

TMAre you an avid gardener?

CVNo, I'm an avid artist, so I've got no time!

TMIs much of it left as it is? I imagine you wouldn't want to remove any potential subjects.

CVYes, there is that. I don't control it in order to paint it, as it were—not quite like Monet!

I try and make my touch—the sense of my hand at the end of my brush and what it does on the canvas—say as much as it possibly can, just within those limits.

TMI am curious about how 'attaining truth' through fastidious observation contradicts with how certain works leave out 'facts'—such as your lithograph Windows (2017), in which thin twigs and leaves foreground five small windows. You noted that it was a conscious decision to keep the windows and leave out the rest of the building. Could you elaborate on the 'truth' that you are seeking to convey in your paintings and drawings, or is it something as open-ended as the feeling of wonder towards the natural world?

CVI think it's too difficult to talk about the truth in a general way, but with regards to leaving things out to get towards the truth: it happens through working.

It's obvious that having less distracting stuff gets you towards what you want. But to do that, amongst an abundance of choice, you have to be much clearer about the aim. You really have to finetune your ear to what your intuition is telling you.

I note some things down from time to time, and I was reading a bit of literary criticism by Ali Smith about something that Muriel Spark had written where she sensed that Spark had taken something out of it. Something was missing.

She said that through its absence, you felt the author's presence: 'her very touch'. I thought that was an odd thing to say about a bit of writing, but it's very true about painting. I try and make my touch—the sense of my hand at the end of my brush and what it does on the canvas—say as much as it possibly can, just within those limits.

There's a painting called Buds (2021), and there are some monotypes with buds in. A bud is an incredibly potent form; totally suited to its job. And it's just about to become something rather extraordinary, with a flamboyance that is very often unattainable.

The problem, or question, is how to give expression to the enormous potency of that small bud on a five-foot canvas? I found that by being completely particular about the shape of that bud, that it had the strength to hold its own on a large expanse of white canvas.

Someone who had nothing to do with art once said to me a long time ago, that I seem to paint things that are barely there. And from him, it wasn't a compliment. His comment sat with me for a long time—as criticism tends to do—and I realised that it was a fantastic thing, to have found the right medium to do that.

That sort of sense of barely there-ness suggests the passing of time. It's there and then it's gone. And that's another sort of truth that I'd like my prints and paintings to reflect. —[O]