Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dew Drop

In Partnership with the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Lindy Lee. Photo: Saul Steed.

Lindy Lee. Photo: Saul Steed.

Anchored in an exploration of identity and selfhood, Lindy Lee has created an expansive body of work over the past three decades that fuses Zen and Dao Buddhist philosophies with processes including splashing, burning, and throwing, using materials that she is intuitively drawn to, such as silk, paper, and bronze.

In the process of creating, Lee invites chance into her work, reflecting on the vastness of the cosmos and the interconnection between beings—qualities that are being explored in her major survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), Moon in a Dew Drop (2 October 2020–28 February 2021). Drawing from a phrase by 13th-century Zen philosopher, Eihei Dōgen, Lee evokes the combination of 'infinity within the finite'—of the moon's changeability through its infinite cycles, and the finiteness of the dew drop.

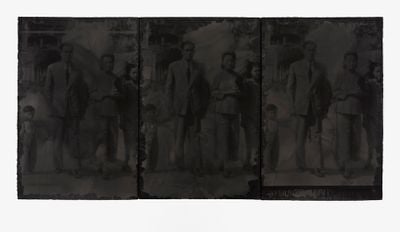

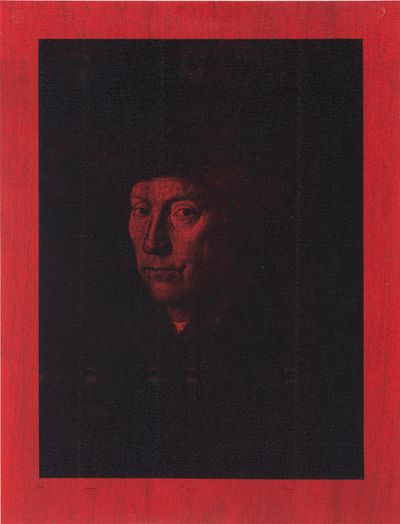

The exhibition traces the artist's trajectory, beginning with her early questioning of her identity as a Chinese-Australian artist. Leaving London to study at the Chelsea College of Arts for two years, Lee returned after running out of funds—what she describes as a blessing in disguise with regards to her personal development as an artist. Upon returning, she began a series of images, appropriating portraits of old masters from the European canon, such as Titian, Rembrandt, Raphael, and Artemisia Gentileschi, passing them through a photocopying machine over and over, allowing layers of carbon to build up and distort the images.

Using the Western canon in this way, Lee came to realise that she was in a sense declaring: 'I belong to the Western tradition.' But later realised that 'if you have to declare that you belong to this or that, then you don't belong'. In belonging, one doesn't question, Lee explains. 'It is just part and parcel of the fabric of what you are.'

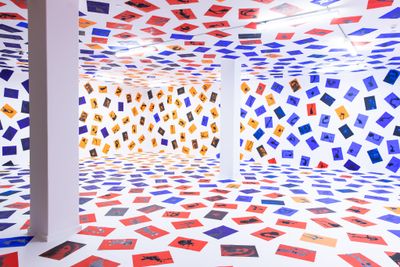

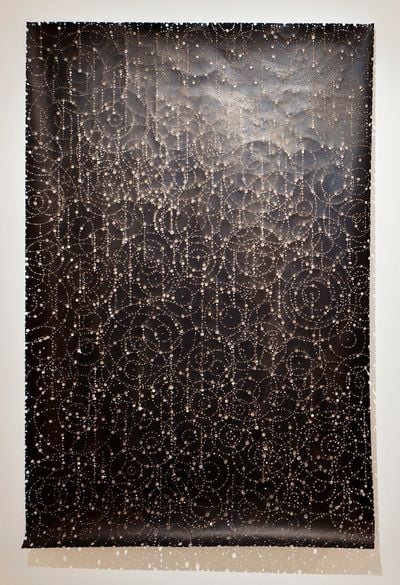

Drawn to connect with and interrogate her Chinese ancestry, Lee arrived at Zen Buddhism, approaching traditional methods such as flung ink painting in her own search for authenticity. One of these earliest installations, remade for the exhibition at MCA, is No Up, No Down, I Am the Ten Thousand Things (1995/2020), which comprises some 1,200 sheets of brightly coloured A4 paper depicting ink splashes along with printed images from art history and her family album. The exhibition also includes a series of iconic singed scrolls, the constellations of burnt perforations on their surfaces recalling the multiplicity of existence and fire as an essential element of the universe.

In this conversation, Lindy Lee speaks about the trajectory of her practice with Elizabeth Ann Macgregor, MCA director and the curator of the exhibition.

EAMLindy, one of the most profound experiences I've had as a curator was watching a discussion between you and Gulumbu Yunupingu during the re-opening show at the Museum of Contemporary Art after we expanded (Marking Time, 29 March–3 June 2012).

It was an extraordinary encounter, in which my colleague Rachel Kent brought your work, with its views on Buddhism and the cosmos, together with a senior artist and Aboriginal Elder and her view of the universe. Could you talk about how you felt about this incredible encounter?

LLFirst, I don't think I can thank Rachel Kent enough for bringing Miss Yunupingu and I together in that same exhibition. It was unexpected, and it was an incredible insight on Rachel's part. When I saw Miss Yunupingu's work in Marking Time, something beautiful tore in my soul. Apparently she had the same experience of my work.

I remember Miss Yunupingu was doing a floor talk and I had arrived to watch, to simply be in the background, but I think you, Liz Ann, decided to call me up to the front, and we both started talking about each other's work.

We both started to cry because for Miss Yunupingu, my burn paintings, my fire drawings, recalled the dreamings of her father, of her people, because in her dream time, her people were born out of fire. The sparks in the drawings themselves were like the birth of her people. For me, her work was the net of Indra, this immense cosmos that she presented. So there we were, both of us trying not to cry in front of the audience.

EAMThe audience was crying too, by the way.

LLIt was a really profound moment. I'd always had an idea or thought that there was something so resonant between Indigenous Australian spirituality and ancient Chinese spirituality. And I think that came through in that show; not just visually, but spiritually.

The spirits of these two traditions really came together and resonated in an authentic way. So authentic that it made the artists cry, and it actually made the audience cry. It was probably one of the most profound moments of my life.

EAMYou have a habit of creating wonderful titles. Could you talk about the title you gave to your fabulous show at the University of Queensland Art Museum, The Dark of Absolute Freedom (20 September 2014–22 February 2015)? How does this relate to authenticity?

LLWell, I think the struggle of my life and probably everybody's life, is to find what is authentic; what is true. Ironically, my early photocopy works were about authenticity. 'The dark of absolute freedom' is a phrase that I found in Ad Reinhardt's notebooks. Ad Reinhardt has been one of the most important artists in my life, and I love his notebooks. His notebooks were filled with direct references to Daoism and Buddhism.

I think the struggle of my life and probably everybody's life, is to find what is authentic; what is true.

The dark of absolute freedom is the dark of not knowing. This kind of not knowing is not about ignorance, but the capacity to let go of preconception, and therefore to meet exactly who you are in this moment. To not know is to let go of the constructions about the self. And when you let go of those constructions, you're ready to meet this moment that you're actually living. And that is authentic.

EAMI remember one of the most striking things about your work was this use of bold, single colours, which seemed linked to some kind of symbolism, but it wasn't something you were really foregrounding at the time. And you've continued that.

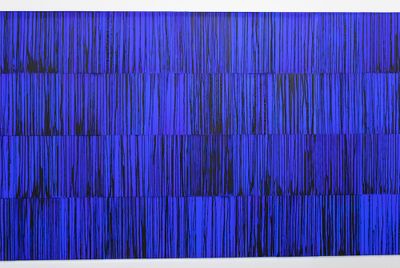

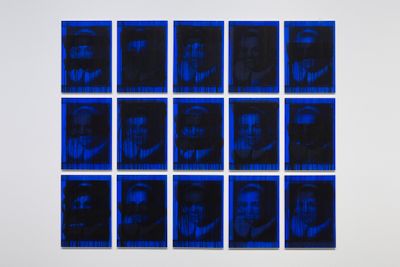

One of the new works in the show, Under the Shadowless Tree (2020), uses this amazing blue that just zings off of the canvas. Could you talk about the inspiration for the way in which you use colour?

LLI used to be embarrassed to say things like it was all intuitive, but I no longer feel that, because art can at times be overly intellectual. The colours are actually the colours of my autobiography.

It seems like every five years in my life, there is a strong attraction to something, a material of some kind, and colour is a material. At first, it was black, and for whatever reasons I just had to use black. All my work was just black and very monochromatic, very monochrome.

As you use a material of any kind, like a colour, it begins to reveal its meanings to you. I love what Maurice Merleau-Ponty once wrote, that we understand colour through our relationship with the world and our association, so when we see the colour red, we're also seeing the colour of a sunset, blood, or that red dress your mother might have worn.

Just by virtue of existence and perception, colours align with meaning, and I was to discover that before I even read Merleau-Ponty. There has been a sequence of colours in my work.

There was black, which I now understand to be the colour of mourning. There's a huge sense of grief in my life, but black is also the colour of mystery. A number of years later, it was the colour red, and it had to be a specific red. Every single colour is very specific. And that red is about blood ties. It's about the vitality of being. It's about corporeality; our bodies. I'm saying this so simply now, but these things had to be revealed to me as I was working with them.

The next colour was blue—that electric blue that you're talking about—and that's the colour of spirit; the deep, mysterious thing that moves through us. I'm not calling it God or anything like that, but it is just something palpable that we share.

Then there was purple, which is actually the combination of blue and red. At that point, I was going through a lot of personal difficulty. The colour purple is a mixture of blood; of life and spirit.

Then orange came about. You have to understand, it's a compulsion. I'd be thinking, I hate orange. It's too gaudy. Who uses orange? But I was compelled to do it. Sometimes the colours were signalling something that was about to occur—a presentment of some kind.

We consciously live in our bodies, but we are actually very much part of a greater body—the body of the world.

That was about the time when I started to become interested in Buddhism. So the orange came before the Zen, and then I began to realise that orange is a Buddhist colour, and it's about the goldenness in life, even in pain.

The last colour was green, and that is the most poignant colour for me. At some point, I was walking through Chinatown and I saw a green jade bracelet, and I really wanted it. It wasn't just a fanciful desire to have it; it was a soul thing.

Anyway, I bought it. It was terribly expensive; I couldn't afford it. As soon as I put it on, it kept saying, 'Go figure,' to me. This green colour is the colour of the ocean; of birth and death. I've had 20 years of these kinds of intuitive responses, but I had no idea why this one came to me.

About a week later, I got a phone call from my brother, and it was with the incredibly heartbreaking news that my nephew had cancer. I flew to Brisbane immediately, where my family was. Before I left and went back to the airport to fly home, Ben took me by the hand and he said, 'Come to my bedroom, Auntie Lindy, I've got something to show you'. He was a young man in his late teens, perhaps 20 at the time, and nobody had been invited into his bedroom for like a decade.

His room was entirely decked out in green, and it was this specific green. I didn't say anything, and he said, 'Oh, Auntie Lindy, this is my favourite colour. I just love this green.' But what he wanted to really show me was under the bed, and he pulled out a sheaf of drawings; some 100 or 200 drawings that he'd accumulated.

He said, 'Auntie Lindy, I've never shown these to anybody, but I want to be an artist. I'm sick, but I needed you to know that.' At that point, I understood nobody was really talking about it, but Ben was never going to recover from this cancer.

I sort of knew my job was to make sure that Ben knew that no matter what happened, his creativity, who he was, was intrinsic to him and nothing could ever destroy it, and that while he lived, we would celebrate that. And so we did.

Ben died. Then later, a friend of mine sent me an article in New Scientist, and it was about the colour of the universe. The colour of the universe is wasabi green because it is the combined colour of the death of a star and the colour of a star being born. When you combine those colours, it is this green.

As you use a material of any kind, like a colour, it begins to reveal its meanings to you.

We consciously live in our bodies, but we are actually very much part of a greater body—the body of the world. Intuition is really about a kind of unmediated contact and connection with that. The colours, as they've accumulated, are very intense and, curiously, when I went to Tibet, I realised that these colours that I had been using over 20 years were actually the colours that adorned Buddhist temples.

I have no rational explanation, but that's how it is.

EAMI first came to Australia in 1993, and I was very fortunate that a mutual friend of ours, Lyndal Jones, put together an itinerary for me in Sydney that introduced me to many fantastic women artists. Your studio visit was one of the highlights.

I remember looking at this very strong Chinese-Australian woman working on these photocopies of these white, European heroes of 17th-century Western art—they were actually the very antithesis of what you looked like—and I was very struck by that disjuncture.

LLDisjuncture is a really beautiful way of putting it. There is something weird about this Chinese face and me doing photocopies of Rembrandt, Raphael, and Artemisia Gentileschi, and that actually sums up the kind of pain and crisis of identity I was going through, because everything in my childhood, everything on my horizon, was a reference to the West.

I needed to find my belonging within that. And it wasn't until later that I realised that I could never belong in that sense. And, of course, that opens up the most delicious Pandora's box for an artist, because an artist's life is about interrogation of the self in the world.

EAMI was always interested in why you decided to be an artist, because you didn't come from a background that would immediately have pushed you in that direction. I am reminded of how you were told at school in that stereotypical way that an Asian girl should be studying mathematics. Do you remember what really triggered you to begin thinking about how to express yourself as an artist?

LLI often love to blame my high school maths teacher for making me into an artist! What happened is that when I was reading a romance novel underneath the desk in class, Mrs Palmer caught me and hauled me to the front of the class and said, 'Every Chinese girl is good at maths, Lindy Lee. Why aren't you?'

At that moment in my little heart, I threw down the gauntlet and said, 'Well, this little Chinese girl is not going to be good at maths.' It sounds so straightforward, but it was really quite painful. I failed at maths. I was never going to be the doctor or the pharmacist that is the tradition for Chinese aspiration.

As a child, I used to draw all the time, and that was my way of connecting to the world. It was that visual language. I remember lying on my belly on the veranda at Kangaroo Point in Brisbane. The sun was filtering in and the dust motes were floating—in my childhood imagination, this was cosmos; this was magic. I wanted to be able to portray that magic.

EAMHow did your parents respond to you wanting to be an artist, or was it something you kept very much to yourself?

LLMy parents were too busy, I think, trying to make a living. They wanted me to go to university. My dad wanted me to become a pharmacist. Obviously, that was never going to happen. So when it was time for me to go to university, I actually lied. I just said I was going to university. They didn't even ask me what I was going to do. I was going to be an art teacher.

Let me be frank. For the first few years after I left high school, I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I actually didn't think I could be. I tried to do everything else, including art teaching, becoming a graphic designer, those sorts of occupations, which are very valuable, but they're also the traditional ones that women do because at that age, being a creative woman is not on the horizon.

With the study of Zen, the question of identity becomes more expansive.

Anyway, to answer your question about how my parents felt about it, they didn't know. I just lied. I said, 'I'm going to university now.' Also, because I was a girl, it didn't really matter that much to them, because they just simply expected that I would get married and have children.

They were pleased that I was going to university. They weren't particularly fussed, really, about what I was going to do. And so I just kept saying, 'I'm just going to study.' But what I was studying was art.

EAMThere weren't many female role models either. In your roll call of great European artists, the one that stands out is Artemisia Gentileschi, because she was one of the few female artists working at that time who had any visibility. The double bind—being both female and Chinese Australian—must have been quite hard. It was very hard.

LLOne of the only people in my horizon at that time was Betty Churchill, which was amazing. She was my first art history teacher when I went to teacher's college. She was wonderful, but she wasn't an artist. So she wasn't a kind of role model, but I guess it was my first encounter with strong woman with the power of knowledge.

And then there was Davida Allen, who was quite popular, but they were the only two. And I didn't know them very well, but they were the only two on my horizon. So it just never really occurred to me. It was never affirmed inside me that a woman could become such a thing as an artist.

Artemisia was a mind-blowing moment for me. When I was in Italy, I soaked up all the most fabulous paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. I was in the mindset that of course, they're all men. And then I look at this painting, and it was Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1612–1613).

I thought, 'Oh my God, that's such a violent and powerful painting.' And then I look at the label and I saw that it was woman who did it. And I had no idea. Thankfully, these days, we don't have that kind of attitude. But I was in my early twenties, struggling with the idea of becoming an artist; struggling with having the courage to just do it. And there was this magnificent painting that expressed so much and so powerfully, and that set something going inside me, which hasn't stopped.

EAMSo you came back from Europe, having immersed yourself in the great artworks of the past, and you attended a conference about Chinese-Australian art. I think you had a bit of a light-bulb moment about your work there, talking about this issue of being a Chinese-Australian artist, right?

LLThat conference was really interesting. At that stage, I was a very young artist. I had just graduated from art school and had started to do these photocopies of great masters from Europe, and for a number of theoretical reasons, these works were sort of upheld as embodying something of the time.

I was invited to this conference, which had to do with China and Australia. I remember thinking I have nothing to contribute here because I'm Western. Then I got up onto that podium and started to talk and found myself saying these words like, 'I'm doing these images, which refer to the Western canon, to declare that I am Western, no matter what I look like.'

The moment those words came out, I realised I was thunderstruck by my own delusion and ignorance. If you have to declare that you belong to this or that, then you don't belong, because in belonging, you don't question it, it is just part and parcel of the fabric of what you are. The very idea that I was in fact interrogating that meant there was a deeper question.

I love those moments of existence that kind of slap you in the face, because they cause you to go deeper and ask the more profound questions.

EAMIn that process of discovery, you also came to Buddhism, which became a guiding force in your life and art and continues to be so to this day.

It strikes me that Buddhism was almost waiting for you to discover it—the thing that was going to make sense of your life and your art. Do you think that's the case?

LLIt was almost a kind of Damascus moment, in terms of Zen Buddhism. I'd started being vaguely curious about Buddhist philosophy, just because I was trying to reach out in some sense to my ancestry. And out of curiosity and perhaps more truthfully out of a very deep, personal necessity, which I wasn't to understand till many years later.

I ended up going to Sydney's Zen Centre one evening and I walked in and most of me was just shocked. There was an altar, there was a statue of a Buddha, and people were chanting sutras. They were doing prostrations.

I was thinking, 'This isn't me. I'm a late 20th-century woman. I don't do this kind of religious ritual stuff.' And I was just like, 'Okay, I'm in the wrong place.' But the moment I sat down on one of the meditation cushions, there was this overwhelming feeling of coming home. It was so overwhelming I wanted to throw up, because it was confronting every belief that I had accumulated about myself.

If you have to declare that you belong to this or that, then you don't belong, because in belonging, you don't question it...

As I began to study Zen more deeply, I realised that, in Zen, the question is not just about identity, but the nature of what exists in all phenomena. So the nature of me is not just my identity; identity is a small fragment of what I am. And in Buddhist philosophy, you are the accumulation of all of history; of everything in this individual moment.

The title of the show at MCA Australia, Moon in a Dew Drop, comes after Dōgen, who is a Japanese philosopher, and my favourite philosopher of all time. In his phrase, the moon stands for infinity, and also mutability; changeability.

The cycles of the moon are infinite, while a dew drop is finite—it will evaporate with the morning sun. In the image of the moon in the dew drop is this this wonderfully poetic feeling of infinity within the finite.

With the study of Zen, the question of identity becomes more expansive. It's about this bigger thing. It's more about the self, and the project of the self, which is unending. We grow all the time. We are all different from when we were three years old.

So the project of identity is about trying to describe what you are. The project of the self is the acceptance and curiosity of how the world flows into you and how you flow out into the world to create this moment.

EAMWe've now moved into Covid-19. You and I started working on this show 18 months ago, and we could not have imagined how different the world would be. Looking at the show now, it seems to me that the discussions in your work around the cosmos, that we are part of a wider universe, are so emblematic of the moment.

We all know that one of the things that Covid-19 has caused is the breakdown in our relationship with the universe and with other creatures, and indeed your discussions around identity relate so much to the rising racism towards Chinese people as the so-called source of the virus, that's been fuelled in certain quarters. What do you think about these connections, now?

LLWe are in such curious times. People are very divided, and I think they're divided kind of into many categories. But the two categories I'd like to talk about are those who are willing to work together, and those who only see an infringement on their own personal freedoms.

One of the most beautiful images of the universe is the net of Indra. The universe is likened to this infinite net and at the ties of each knot of the net is a jewel that is perfect and brilliant and utterly unique, but its beauty, brilliance, lustre, and singularity are utterly dependent on the fact that it is receiving the light of every other jewel in the universe. That's us.

None of us can exist alone. We all have to pull together, because we're actually part of the same fabric. That fabric is the cosmos, and what I mean by cosmos is that it is the length, depth, and breadth of everything that has happened, is happening, and will happen in the future.

We can't extricate ourselves from that. And we can't extricate ourselves from our relationship to each other and everything in the world. Everything has caused the existence of you and me. And we have to respect that.

The Covid-19 pandemic, in a sense, is a testing and trying time. It's testing us to come together, which is one of the best things about being human. There's another point, which I think is related, but maybe it's a bit abstract: human life is both historical and unhistorical. Each of us is historical in the sense that everything that has occurred, culminates in this moment of every single body's existence.

But simultaneously, we are unhistorical. This moment has never happened before and will never happen again. And that to me is a very poetic, but poignant and important way of valuing life and existence, and also highlighting our responsibility to uphold that value and that respect.

None of us can exist alone. We all have to pull together, because we're actually part of the same fabric.

The Covid-19 pandemic is just this unbelievably extreme example of this split in the road, shall we say, that humanity can go. It can go towards this fundamental reality that we are all connected and that we must do this together. The other fork is each to their own, and that's just going to destroy us.

EAMYes. It was particularly poignant for you, living on one side of a border that's been closed, meaning you weren't able to see your mother on the other side of it. It is very sad to see these restrictions and attitudes towards retreating into ourselves, instead of reaching out.

I think it's causing all of us to think about how we operate and how we can continue to think about a different kind of world—thinking about how we can reach out and try and deal with some of these other issues that are arising.

Black Lives Matter is another very potent issue for all of us, as well as attitudes towards diversity of all kinds. This is something that we've been very concerned with here at the Museum over the years, in trying to make the Museum as open and diverse and inclusive as we can, and how much further we need to go with that—working almost against the isolationist tendencies within the Covid environment, where people are not coming together.

There aren't these opportunities, even in an office, to stop by and have a chat with someone who has a different opinion, or people are getting locked into their corners, as it were. I think your show is a very good moment for people to reflect on metaphor of the net of Indra, which is such a powerful one.

LLThe Covid-19 pandemic has also been a very emotional time for me. Not because of the isolation, because an artist needs isolation, actually, but because of racism, which is the one thing that will push my buttons and make me so extremely angry and volatile.

Day after day, I was watching the Black Lives Matter protests and hearing tales, especially from my friends in New York who are Chinese, of abuse. Then there's my niece, who's an emergency doctor—she doesn't need to receive this kind of abuse. It makes me so angry, I don't even know what to say about it.

In any troubling time, whether it's personal, social, or global, we have the opportunity and responsibility to grow with it and to seek the best of what's inside us and communicate. Of course, it's hard to be separated from family, because of border restrictions and everything, but it also means we have to try harder to really communicate. Maybe that's a silver lining.

Instead of taking things for granted, we have to invent ways. We have to refresh ourselves in the way we make relationships, so that becomes a conscious thing. We don't take it for granted at this time.

EAMYour exhibition, if you don't mind me saying, acts like springboard for these kinds of conversations, but it is also a place of refuge. I think you're right—we do have to think of other ways, and that's why art is so important. For me, what makes a really great work of art is when it can elicit all these different levels of responses.

LLThe way I like to describe the importance of art is that when you encounter somebody, you could describe them endlessly, but that will never, ever, ever sum them up. We always exceed any description. And that is because there are 10,000 invisible things that are inside of us that make us who we are. The importance of art is that it brings this invisibility into life, into materiality, so that we can look at it.

So art has an extraordinary job. It allows us to reflect on who and what we are, how we're connected to the world, and these are largely invisible things. We have to be able to reflect on what we are.—[O]