Sean Scully

Sean Scully in his studio. Photo: Peter Le.

Sean Scully in his studio. Photo: Peter Le.

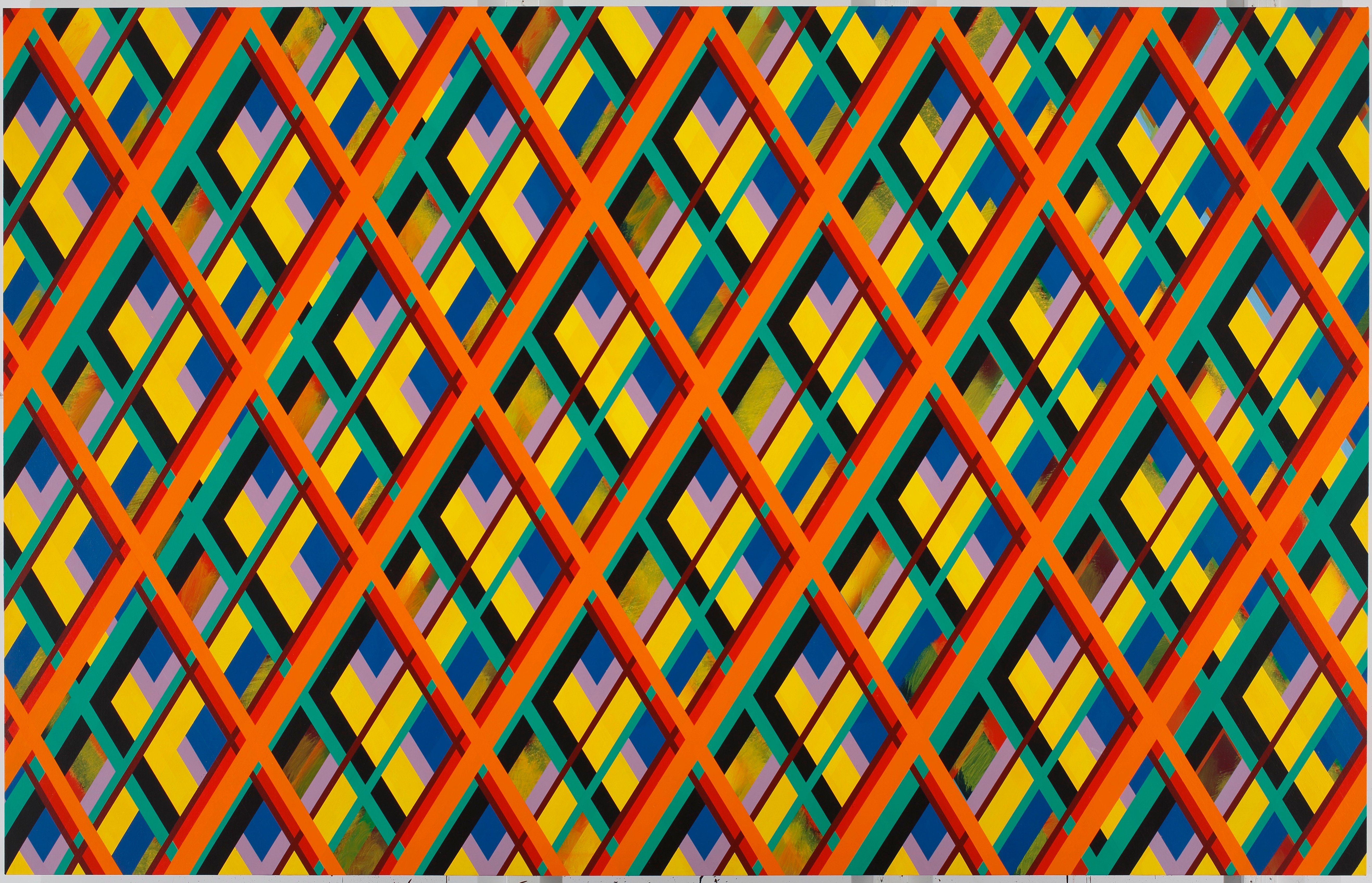

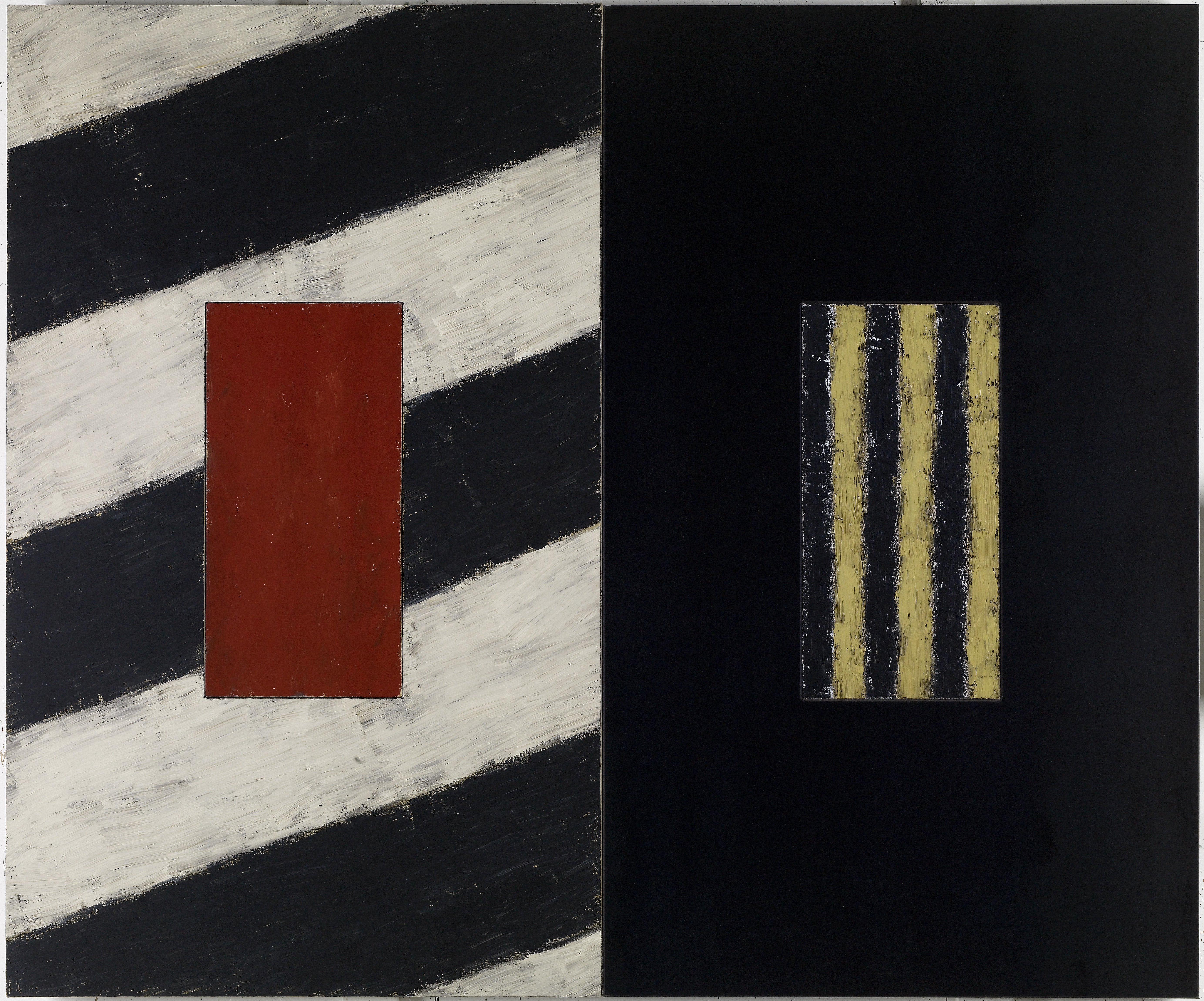

Already recognised in the Western art historical canon, 71-year-old Irish-born, American-based artist Sean Scully's oil paintings are characterised by their geometric constructions and painterly expression.

These two disparate modes marry in the artist's canvases and act as a retort to the rigidity of last century's hard edge-abstraction. Scully has worked through the history of modern formalism, abandoning clean lines and energy-devoid canvases early on for densely layered colour and emotion.

The thresholds between rectangles, squares and criss-crosses in his large-scale works are blurred as a result of several loose and spirited applications of paint. Without fixed boundaries, the shapes seem to breathe. In person he advocates for the return of feeling to art, asserting that painting is both a noble and risky endeavour.

Scully's exhibition Sean Scully: Resistance and Persistence (6 September–9 October 2016) at the Guangdong Museum of Art in Guangzhou is curated by Philip Dodd and includes paintings made over the last 50 years.

It is Scully's second career-length exhibition in China, the artist having first showed Follow the Heart: the Art of Sean Scully, which opened at Shanghai Himalayas Art Museum (23 November 2014–25 January 2015) and moved to Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts Museum (CAFAM) (13 March–23 April 2015).

EAIn an interview with Eric Davis in the 1990s, you said that painting was the most dangerous, insecure and potentially the most profound thing you could choose to do. What about painting is dangerous, and what is its potential for profundity?

SSWell, of course it's visual, and a deeper truth because it's visual. In England, it's very difficult because it's not a visual culture. But China, America, and to some extent Germany and many other places, are visual. The world is visual. And it's becoming more so as it becomes more technological, and travel becomes disconnected from the landscape. So then it becomes a question of seeing things four-dimensionally and recognising things visually. So I'm part of this, and I make work out of that material. And dangerous? Yeah, it's very dangerous professionally.

The thing about my work is that it's not remote. I've tried to make an abstraction, and I've found this hugely difficult in the beginning, although it's getting a lot easier now... I make metaphors that are very obvious. I make paintings with colour that you can recognise, and titles that you can recognise.

If you think about the odds: I was explaining it to some lovely art students here yesterday. They were asking, 'what if people don't like my work?' So, okay. To get into art school: one in ten. To get into graduate school: one in ten, that's one in a hundred. To get something afterwards, that's one in ten, that's one in a thousand. To get really something, that's one in ten thousand. Do you like those odds? So, in that sense, it's super dangerous. And, it's also very much about throwing the ladders away every time. You have to be suited for it. You have to be like me. I'm suited for it.

EAHow so?

SSI'm very tenacious intellectually, and very hot emotionally. I think that's like a galloping stage coach, you know, with a black horse and a white horse pulling it.

EAYou've said that your paintings can drive you crazy and that they offer you no relief. When I heard this, I thought of music theory: when a chord has an element of dissonance, there's a tension that makes it much more interesting than simple harmonic cohesion. Is relief something that you've ever wanted, or is it completely uninteresting to you?

SSThat's a nice metaphor. What I meant by that: in my paintings, I don't paint space. I paint things. I paint the stripe as if it's a kind of life and death. I mean, you've got to paint something, you can't paint nothing. So it's like Van Gogh again. Everything in a Van Gogh is something. You know, there's no backup. There's no stepping back. I like stuff without rest. I like intensity piled upon intensity piled upon intensity piled upon endurance piled upon relentlessness.

The world is visual. And it's becoming more so as it becomes more technological, and travel becomes disconnected from the landscape. So then it becomes a question of seeing things four-dimensionally and recognising things visually.

Piled upon some more of that. When I was coming up in the elevator [of the hotel in which the interview took place], you know what they were playing? This is what I love about China. They're profound people. They were playing Kodály. Where are you going to hear a Kodály cello sonata in an elevator? You're not going to hear that anywhere else—you hear Mantovani. And that's the kind of stuff I like. I like the relentlessness of I suppose that kind of Eastern European angst.

EAThat leads me to my next question. I'm interested in your appreciation for conviction. You've said that even if you see an ugly artwork, if you can tell that the artist created it with confidence and earnestness, then you can find beauty in it. How do you identify conviction, and do you see it in the work of the new generation of painters?

SSYeah, there's a new generation of painters that I like very much. Well, I see it certainly in the work of Ding Yi, for example, a Chinese painter. I see certainly in the work of Sterling Ruby and Charline von Heyl and Christopher Wool. These people, I think are very interesting and I'm totally engaged by their work. What's happened, I think in abstract painting, is it's becoming less conceptual and more emotional in this generation. Hotter. More physical, more colour, it's less cool than it has been for a very long time.

EAIs that a good thing in your opinion?

SSFor me it is. Because that's where I live. And I want some company.

EAHow does your work function in China, where the development of abstraction hasn't followed the same trajectory as in the West?

SSThe thing about my work is that it's not remote. I've tried to make an abstraction, and I've found this hugely difficult in the beginning, although it's getting a lot easier now. If you know anything at all about my life, you know that I've struggled, and now I'm becoming very recognised. But it's taken me a long time. I make metaphors that are very obvious. I make paintings with colour that you can recognise, and titles that you can recognise. For example, I gave a painting to CAFA. They asked me for a painting and me, like a fool, gave them a painting which means that more people can ask me for a painting. There's a painting that I made listening to Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds' The Weeping Song.

It's so profound, that song, and there's no relief. I made this painting with horizontal, blurred stripes very aggressively painted with a lot of reds, a lot of passionate colour, with the drips at the bottom. The paintings looks as if it's expressing The Weeping Song. It has rhythm, but it also has a kind of sadness in it. But a great exhilaration, as well. I'm not a depressed person, as you've probably noticed. I have a lot of energy. I think people can relate to my work very well. You know, there's nothing about my work that's overly intellectualised, so it's accessible. One of my projects was quite simply put, to popularise abstract painting without lowering the bar. Easier said than done.

EAAnd perhaps to once more popularise emotion in abstract painting, because for many years it had fallen out of fashion.

SSAnd cool, and ultimately rather elegant and decorative. It lost its connection to life.

EAIt lost its guts.

SSYes, its guts. Perfect word.

EAHow does drawing factor into your practice?

SSGood question. The paintings I make at the moment, I don't draw. It's the first time I've made paintings where I haven't drawn. I find that very interesting.

EABefore, did you draw a grid to plan your paintings?

SSWell, if you look at the Wall of Light paintings for example, I would draw them out with charcoal on the end of a stick a la Matisse, with distance, you know. So I was kind of composing, because they weren't actually a pure grid. Some bands were this big and some were this. But it looked kind of like a grid. it was a grid with feeling, or intuition. But with the Landline paintings, which are these bands that go across and that relate obviously very much to the landscape, and I've taken photographs of the edge of the sea, and I've written for example on a little girl called Ava who was dying of cancer, and her father bought this photograph for her, because she wanted my photograph when she died. It touched me unbelievably, and I wrote on that.

So I try to make my work accessible for people so that people can really relate to it without a filter, without a tonne of knowledge. Even though some of their references are different to mine, but some of my references are different to yours, and some others are bigger than other mothers. We're all separated.

EAWhat is something that art schools should teach young artists which they don't?

SSI think that craft is very important in art, because as we become more technological, the materiality of life, or the ability to make something becomes extremely important.

They do that in the Chinese academies, and that's very important. But in other art schools, particularly in England, they get rid of the departments and they get rid of the idea of craft. And making art, whatever you make, or even if you write a poem, a lot of it is craft. It's 90 percent craft to get you up to the point where you might start making art. It's only a little bit of art that's supported by a lot of craft.

EAI studied painting at university in Canada where it's also completely conceptual; students never learn how to apply paint to a canvas.

SSYeah, you don't understand the relationship, that beautiful relationship between you and the body and the material that you make something with. I always think it's a really nice example to give that Daniel Day-Lewis—who appears as light on a wall most of the time, and is in my opinion, the greatest film actor ever, he's a genius—he makes shoes. He makes shoes for people.

EAReally?

SSYeah, as an antidote to this nutty life that he leads.

EADo you have an antidote like that?

SSWell, yeah, I have my son now. But of course I'm also connected to the material of life much more than an actor. And I never wanted to be an actor. I could have been an actor, easily. But I never wanted to be one.

EAWhy not?

SSBecause it's not enough of an object. It's not enough of a thing. I think I wanted to make something eternal. When I write about Masaccio, for example, or I wrote on Cimabue's Crucifix (c. 1265), this really touches me very deeply. This is what I like.

EAYou speak about beauty often, and it's obviously a very important part of your paintings. I wonder how you court it, how you chase it, and if it ever slips away. If so, do you abandon the work or do you press on and fight through it?

SSI almost never give up on my work. I think that beauty has to contain character. This is a very old and difficult argument. Beauty has become, in a certain sense, unfashionable. But Sigmund Freud said that human beings need beauty. He didn't know why, but he knew that they do. And there was a time, way back—because I've had my eye on China for a long time—when the Chinese government recognised the principle of beauty, and said that beauty was important and people can engage with the notion of beauty. You can't take it out of human need, but what it is, of course, is constantly changing.

The Olmecs used to try and enlarge their noses, and then you see these newscasters on television with these tiny noses and they look like ferrets. So these notions of beauty are not fixed. But my notion of beauty has to have dimension. It can't just be something that looks good. I'm never happy with that. I made a few paintings that are like that. Like one painting in the show, called_Pale Fire_, was characterised once by a very nice curator, a friend of mine. And she said, 'that is like a beautiful woman in a red dress.'

EAIs it titled after the Nabokov novel?

SSYeah. And I thought of it as almost a portrait of America, which is a pale fire.

EAThat book is about a foreigner in America as well.

SSYeah, which is me. —[O]