Dexter Dalwood Rethinks Painting

Simon Lee Gallery | Sponsored Content

In Dexter Dalwood's paintings, the canvas is not only a surface for replication but the resting site for the medium of painting—a contemplative space that the artist adapts and evolves.

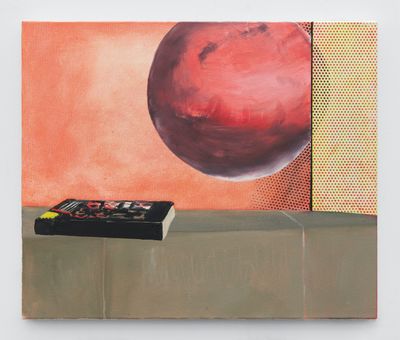

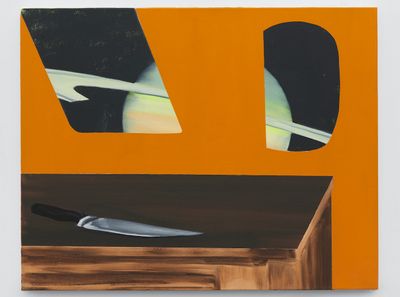

Dexter Dalwood, 2059 (knife) (2021). Oil on canvas. 60 x 72 cm. Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery.

For his second exhibition at Simon Lee Gallery's Hong Kong space (10 September–30 October 2021), the Bristol-born painter carries on with his meditation in a new body of work that projects almost four decades into the future, hence the title 2059—a decade later than Blade Runner 2049, Dalwood points out.

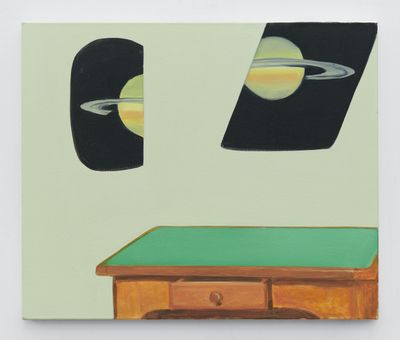

Each of the works in this series is scaled to the size of Jean-Siméon Chardin's House of Cards (1737), an oil painting on canvas in which a small boy sits at a wooden table fully absorbed in building a house of cards. The tower of cards can be seen as the frailty of human endeavours, like construction and creation: a single breath could collapse the structure.

Repetition and seriality point to an exhaustion commonly attributed to late modern artworks, in which distance and departure is achieved through return.

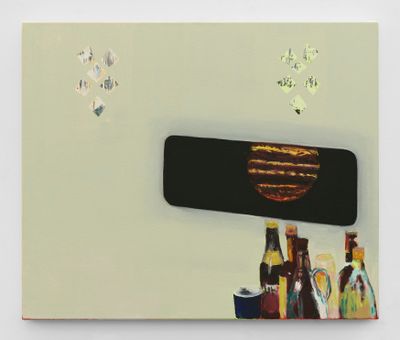

In 2059—a body of work that Dalwood describes as 'both intensely personal and speculative'—the artist builds on this 18th-century allegorical painting to offer a reflection on the medium today, stretching his references across time to juxtapose classical still-life motifs with bright planets and hovering galaxies.

Notions of circularity emerge throughout in the circular motifs of planets, O-shaped fruit bowls, rounded portals, and an allusion to Cézanne's The Card Players (1894–1895), a five-painting series that capture various groupings of men playing card games, which preceded the artist's most acclaimed years.

Repetition and seriality point to an exhaustion commonly attributed to late modern artworks, in which distance and departure is achieved through return.

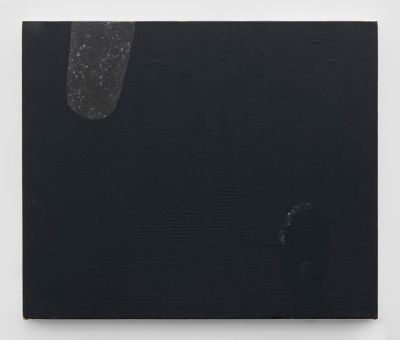

Yet the paintings in 2059 seem to reflect a willingness to let go of the 'scaffolding' of established references, even as they are made. As if in demonstration of this release, five playing cards can be sighted in 2059 (cards) (2021), tossed in the air and hovering in a cage-like structure floating in space.

Throughout the exhibition, viewers are reminded of the artist's presence with explicit allusions to cutting through space.

In 2059 (knife) (2021), a greenish yellow Saturn-like planet is robbed of its third dimension, sliced in two by the knife resting on the console table. The planet hovers behind the table against bright orange walls, the edges of its portal rounded to resemble an airplane window.

2059 (bath) (2021) evokes a similar interplay between motion and stillness plotted against lilac tiles and a bathroom sink. A black hole is reduced to a poster plastered on the mirrorless wall, its massiveness easily forgotten as it is flattened into an image.

The picture of space is sharpened, while the ceramic basin that occupies physical space appears aged. Objects in surroundings blur in reflection, just as thoughts gain clarity.

The cycle of making and unmaking is prominent in Dalwood's process, as exemplified in earlier paintings like Kurt Cobain's Greenhouse (2000)—a detailed sitting room looking onto a cityscape assembled from collage, a method that is equally composition and tearing apart.

Yet 2059 departs from Dalwood's early paintings, which are known for their complex arrangements that prompt viewers to revisit significant places that have permeated the collective imagination: bedrooms of Hollywood stars, murder sites, tropical jungles that veer apocalyptic, and politically charged settings like the location of a 1961 attempt by the U.S. to overthrow the Cuban government.

Often, these places become unrecognisable post-reconfiguration, distorted through physical alterations and perspective.

By reconfiguring both past and future in the present, 2059 demonstrates how painting evolves in perpetual negotiation in order to project a vision for the future.

As Dexter points out, 'the depiction of history is so subjective. There are actual dates when things took place, and then there is the mediated written or depicted version of those events that shifts over time. Thus, our understanding of the past is deeply rooted in how we decide to construct a vision of the future.'

In Brian Jones' Swimming Pool (2000), a drained pool is sighted from the bottom with the English musician who drowned on the premises nowhere to be found, while in Room 100, Chelsea Hotel (1999), where Nancy Spungen was supposedly murdered by musician Sid Vicious, the bedroom is tilted to one side.

In contrast, the newer works of 2059 no longer make direct use of collage as a way to compose images. And rather than focus on sites from history, the artist seems to make the canvas itself, populated as it is with futurist projections, the site of inquiry.

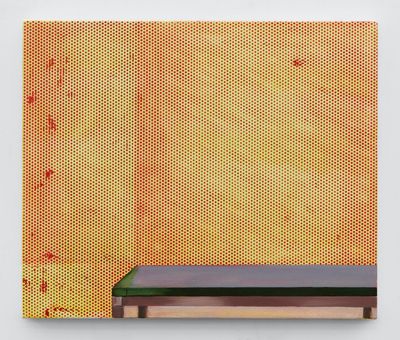

The settings across 2059 are simple, while colour is used to allude to an expansiveness. A similar orange from 2059 (knife) (2021) returns in 2059 (anteroom) (2021), dotted against yellow walls to evoke the in-between space of the present, marked by possibility and waiting. As a whole, the canvas appears empty, with just a hint of a wooden table at the bottom right corner, its smoothness standing out against a yellow background covered in red perforations.

What emerges are sparse compositions that sharpen the focus on the elements that are present and lightens the load of the painting, unburdened from pre-mediated composition.

2059 is significant within Dalwood's practice in its allusion to painting as its own time-space and reflects the artist's ongoing commitment to the medium. By reconfiguring both past and future in the present, 2059 demonstrates how painting evolves in perpetual negotiation in order to project a vision for the future.

Beyond what painting is from the moment we intercept the image, Dalwood invites the viewer to consider what painting could be. —[O]