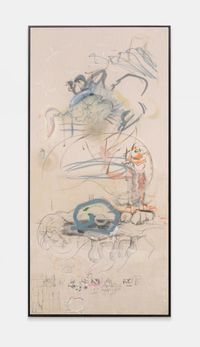

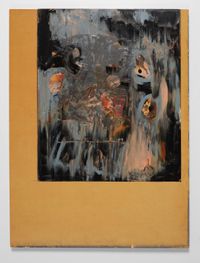

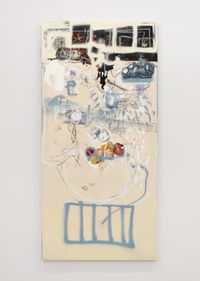

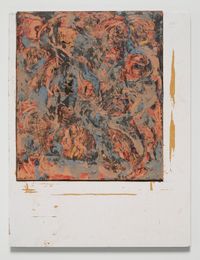

I'm a Restaurant is a show by Uri Aran. The exhibition and its constituent pieces speak in a voice that is both singular and plural, confounding I and we. The artworks do not strive for seamlessness or convincing artifice. Instead, Aran leaves exposed the threads of the mysterious, unstable process by which parts turn to wholes, by which a thing becomes that which we call it (a sculpture, a chair, a restaurant). To do so, he draws from the traditions of assemblage, ready-made, and process art, but remains untethered to any particular mode of making. An attitude of unfixity likewise characterises the works' expression of meaning: they are ambiguous and ever-shifting, changing with each viewer, with each viewing.

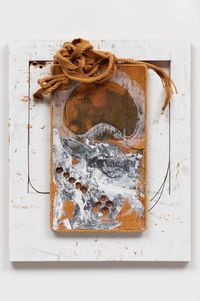

Language runs throughout Aran's works—explicitly so, in the forms of text and recorded speech, but also invisibly, as a structure and subject. His sculptures, paintings, and videos draw from a broadly defined alphabet of forms and gestures, an idiosyncratic vocabulary of things. They seem to reverse the typical semantic flow, in which a word stands for a thing. Instead, familiar objects function as stand-ins for their own names. This phenomenon results from a confoundingly frank treatment and presentation of materials: the things in his works are familiar, unadorned and utterly themselves, and yet completely stripped of context or use-value. They ask but do not answer: what does it mean to mean?

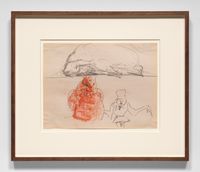

The show moves through a knotty emotional register, rife with dissonance. A sense of comedy, both slapstick and deadpan, permeates the exhibition. But melancholy easily coexists with playfulness: a silly or cute moment can also feel heartbreaking. And of course, everything resonates differently depending on a person's own history: if your dog died recently, a puppy showing off his intact testicles will move you differently than it would someone else, who might find it simply funny or strange. The dog is a screen for individual projection, the viewer's personal subject—and may thus become charged with seemingly contradictory sentiments. Aran destabilises a fundamental hierarchy, moving the non-human to the level of the human: where an actual dog can only hold one feeling at a time, people have the unique ability to experience discordant emotions simultaneously. This sly act of anthropomorphisation transfigures not only the animals that recur throughout his work, but his inanimate subjects as well, which also become nebulous and sympathetic.

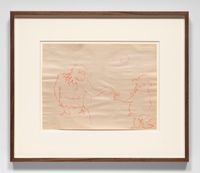

The works' unvarnished appearance belies Aran's meticulousness and attention to craft. Drawing is the essential mode of making for his practice, and he strives to maintain its sense of quickness—its closeness to an idea or impulse—in all his works. He moves freely across genre and media: within paintings, a reference to Cezanne still life sits comfortably and quietly in a field of abstraction, while graphite streaks overlay layers of oil. The sculptures have a casual grace, dancerly in their balance and seeming effortlessness—but close consideration reveals the care and ingenuity with which they have been contrived and constructed. Likewise, the videos' home-movie aesthetic is at odds with the painstaking production process of stitching together and editing found and original audio and footage. The works' lack of gloss and meanness of material makes them familiarly welcoming, as well as semantically and emotionally democratic: each piece invites viewers to connect and engage on their own terms, rather than those dictated by the artist.

A man in a neat dark suit places himself front and centre amid a restaurant staff. The waiters are all dressed in white, the maître d' in black. Each faces the camera, with a plate shoulder- height and horizontal atop his flattened right hand. The man in the suit is diminutive and middle-aged, physically unremarkable. He moves with overstated precision and an ironic soldierliness, an absurd drill sergeant. He proffers a command: a sharp burst of French followed by a double kiss noise and gesture towards the pianist, stationed stage left, who begins to playa light, sweet tune. But It is a false start and the man reprimands his player before counting off. The waitstaff begins their dance, and the tune starts anew, on cue this time. The dancers are inexpert and a bit out of sync, but nonetheless they move as one—stepping out tight circles, kicking their feet, and tossing their plates hand to hand. A perilousness underlies their effete movements, and the sequence is interrupted when a dancer loses control of his plate, which crashes and breaks on the floor. The man in the suit brusquely dismisses him and the dance begins anew. The piano music grows more raucous, as does the dance, and all at once the plates are hurled to the floor, crashing and breaking. It turns to a decidedly French take on a typical Cossack dance: the men erupt in rhythmic shouts, stomps, and claps, linking arms and flailing legs. The already imperfect synchronism grows steadily rougher, but the sense of unity does not falter—in fact, as the chaos builds, so does our impression of these restaurant dancers' interconnectedness and unity. (Le Grand Restaurant, dir. Jacques Bernard, 1966.)

Press release courtesy Andrew Kreps Gallery. Text: Tommy Brewer.

22 Cortlandt Alley

New York, 10013

United States

www.andrewkreps.com

+1 212 741 8849

+1 212 741 8163 (Fax)

Tuesday – Saturday

10am – 6pm