Gary Simmons uses icons and stereotypes of American popular culture to create works that address personal and collective experiences of race and class.

Read MoreBorn in New York in 1964, Simmons received his BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 1988, and his MFA from CalArts in 1990, studying under the tutelage of Charles Gaines, Michael Asher, John Baldessari, Catherine Lord, Mike Kelley, and others. Upon graduation, Simmons established a studio in a former school in New York City. At this stage, he was working predominantly in sculpture, a medium he would return to in subsequent decades. Works from this period, such as Big Dunce (1989), use schoolroom objects to address racial inequality and institutional racism through the filter of childhood experience, themes seen most explicitly in Six-X (1989), comprising six child-sized Ku Klux Klan outfits hanging from a schoolhouse coatrack.

Simmons’ use of pedagogical motifs, in particular readymade chalkboards, led to the formal and aesthetic breakthrough that would inform much of his subsequent work, in which erasure of the image has been a powerful and recurring theme. The tropes of erasure and ephemerality suggest the fleeting nature of memory and histories re-written. Simmons draws from popular culture, music, vernacular, and cartoon imagery, specifically the racist characters of early animations. A landmark piece commissioned for the Whitney Biennial, Wall of Eyes (1993), explored the aesthetic possibilities of chalkboard at a monumental scale. Simmons drew cartoon eyes in chalk over slate paint applied directly to the wall, then deliberately hand-smudged the chalk lines. As the artist explains: ‘I started to think about how images on blackboards can never be fully erased. It was about trying to erase a stereotype and the traces of the racial pain that you drag along with you.’

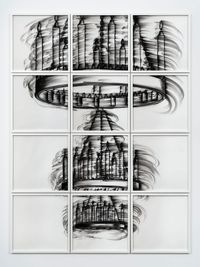

In further key commissions, Simmons has expanded beyond the confines of museum and gallery walls, creating performative and site-specific works which underline a relationship to a trajectory of art history that includes minimalism and conceptual art. For Sky Erasure Drawings (1996), commissioned by the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, airplanes temporarily inscribed vapour stars in the daytime sky in liquid paraffin. For his immersive installation, ‘Fade to Black’ (2017), for the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, Simmons created five monumental wall murals featuring the titles of vintage silent films; the names of largely forgotten movies and African American actors appeared in big typewriter-style letters blurred with ghostly traces. In a recent series of works, Simmons mines the architecture of surveillance through depictions of watchtowers and lighthouses. Deliberately ambiguous, these works collapse the boundaries between signifiers of safety and those of control.

Simmons’ immersion in music has continually informed his practice which draws inspiration from dub, punk, hip-hop, reggae, and rap. Particularly influenced by the genres’ race and class-focused politics, the artist has created a number of works tracing the voices in music that have shaped contemporary culture. Simmons attracted significant critical attention in 2014 for his stacked speaker piece Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark. Inspired by Jamaican sound systems, the work was a living sculpture, with musicians invited to utilise it for performances and then leave whatever configuration they had used for those performances. The work’s ongoing history offers both a contrasting and complementary approach to the record of the past offered by the artist’s well-known erasure series of paintings.

For a site-specific installation commissioned for Culture Lab Detroit in 2016, Simmons was inspired by the guerrilla marketing style of fly-posting to promote gigs. Using found posters sourced from flea markets and the internet, he manipulated the originals, saturating the colours or reworking the texts, before layering onto plywood or canvas. These works evoke the fragmentation between individual and collective memory that preoccupies much of Simmons’ practice.

Text courtesy Hauser & Wirth.