Akira Takayama

In partnership with The 21st Biennale of Sydney

Filming of Akira Takayama's Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Project (2018), on 28 January 2018 at the Sydney Town Hall. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Document Photography.

Filming of Akira Takayama's Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Project (2018), on 28 January 2018 at the Sydney Town Hall. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Document Photography.

There is something deeply evocative about the work of Akira Takayama. His endless fascination with the fabric of society, the creation of culture and the ebb and flow of communities drives a multi-disciplinary approach to the craft of devising theatre. For the viewer, an encounter with a Takayama work is intimate and personal.

Throughout his practice, from theatre director to site-specific performance artist to contemporary video artist, his work sets up a collision between audience and environment. Each work is meticulously designed as a critical provocation aimed to expand the expectations and possibilities of contemporary art. Utilising unconventional artistic practices, Takayama's works dissect power structures, social expectations and the perceived limitations that shape our collective experience of society.

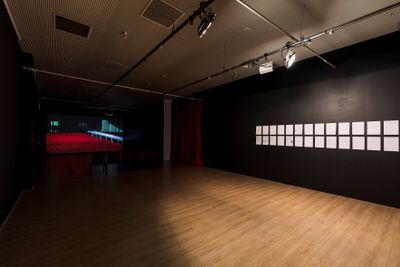

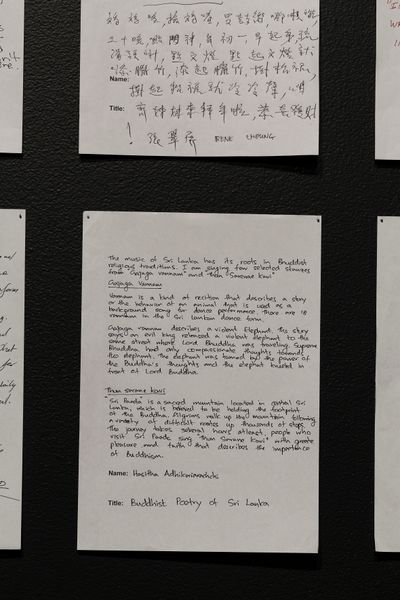

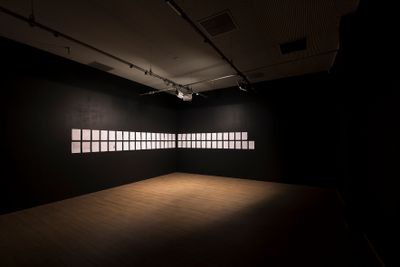

Debuting for the Biennale of Sydney (BoS) (16 March–11 June 2018), Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Project (2018) addresses pressing global concerns of migration, belonging, loss and ancestry mediated through the intimate personal narrative of song. Inviting people from across Sydney to participate, Takayama seeks to elucidate the hidden voices of the city. Once-sequestered songs heard behind closed doors, in whispers and in comfort, now appear centre stage on a sumptuous hanamichi—a long raised platform used in Kabuki theatre that performers traverse before appearing onstage—nestled into Sydney's Town Hall. Captured in video, each song emerges from personal relationships and fateful encounters and becomes, through voice, a deeply personal epitaph. A daughter's longing for a lost father, a mother's call to her once infant child and a woman singing in an ancestral dialect become charged moments of history and identity captured in cinematic luminosity. Together, the songs speak of a city of migrants where culture and connections remain perpetually dynamic and uncontained by borders, oceans and time.

MTAkira, lets start with a burning question, what is a theatre director doing creating contemporary art for a biennale?

AT(Laughs) I am still making theatre! The central concept of theatre is, for me, between the stage and the audience. The experience of the audience is the most important thing of theatre. People may think I have given up theatre, but really everything I do is always theatre.

MTWhile your practice may have evolved since your early theatre days, it still remains underpinned by concepts pioneered in Kabuki theatre and by the likes of Peter Brook and Bertolt Brecht. Your work stretches theatre into the context of contemporary art, conflating two into one and, perhaps, creating a new, reimagined form of theatre.

ATYes, it is very new and very contemporary but at the same time it is very old. The term 'theatre' originates from the Greek term theáomai, which means to watch or to observe, which in turn created the term théatron, the place of viewing. So, contemporary ideas of theatre come from this Ancient Greek foundation that is primarily concerned with that act of watching rather than the performance itself. Most important in my approach to devising theatre is what happens in the spaces between the audience and the stage. It is this observation or encounter that drives how I create theatre.

MTIt is also a concept that is becoming central to how museums and galleries are programming, as they move away from being solely object-focused to becoming more interested in the encounter between objects and audiences. Increasingly, galleries and museums are inviting audiences into immersive, performative spaces that perhaps hint at the collapse of the distinctions between art forms and the development of new, more intertwined, ideas of contemporary creativity.

ATI totally agree. This intertwining has allowed me to work across many disciplines, but I am still focused on creating theatre because it is my foundation. In October 2017 I directed the Wagner Project in Yokohama and it too was an immersive space. For the project, I totally transformed Wagner's opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg; it became not really opera, rather it was like a music battle or a rap. I invited young people and we made hip-hop Wagner. Some people were really angry with my interpretation. The performance was a mix of theatre, of art; it felt like a festival with street hip-hop opera, a DJ, graffiti and, of course, rap. The Wagner Project was a complex production of art that didn't strictly fall into one art form; it could be seen as music, as dance, as theatre, as school or as opera, and I like this direction very much. However, this work still examined the two essential ideas of theatre: the first, and most obvious, being the action on the stage; while the second, but more important, is the creation of an environment that invites people to engage. I think this element aligns most closely with the ideas of contemporary art and the question I would most like to explore: how we can create situations, places or environments that invite people to engage with ideas and experiences?

MTYour craft is as much about creating this invitation to the audience as it is about the objects or acts themselves. What is it you hope audiences experience? Is it simply a shift in perspective or is more complex or more didactic?

ATIt is strongly connected to Lehrstücke, an experimental form of theatre developed by Brecht that explores learning through acting.

MTWhere the audience is implicated and become part of the work?

ATYes.

MTThis element is evident in some of your earlier works where bus trips or walking tours enable you to invite your viewers into new environments. There is a didactic element underpinning the work whereby you challenge audiences to seek new perspectives of their own familiar city.

ATEducation and learning is quite an important element to me, as it was for Brecht, because it has the ability to galvanize people. When Brecht devised Lehrstücke it was during the time of the rise of Nazism in Germany and he wanted to create theatre that could be effective in enacting political change. Lehrstücke enabled people to learn about situations, about politics, and to place themselves in the position of others, all without giving any specific message or answer. Instead, Brecht illuminated many different directions and illustrated contradictions or paradoxes.

MTThis unresolved nature of your work is what I find most intriguing. We live in a highly polished society where everyone curates their digital persona and the art world has evolved into a proliferation of art fairs that house slick, refined presentations of art. In this moment, your work appears as a rupture where the audience themselves activate the artwork. Through their gestures of participation, the work transforms into a live, dynamic force.

ATYes, I don't like to give any answers. People may think that I have given an answer or a message but it is not true. My aim is to create a situation, a paradox or a contradiction where learning can occur. The main essence of Lehrstücke is to create a situation that is open to audience interpretation.

MTThis idea runs through the work you are creating for BoS, which feels like a piece of Brechtian theatre as much as it does contemporary video art. For Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Project you invite the audience to have a moment of reflection upon encountering the work. The work features a collection of Sydneysiders singing ancestral songs on a traditional hanamichi stage, encouraging nostalgic thinking. When listening to the songs of others, the video poignantly stirs personal memories of tradition, loss and family. It is a work that offers an individual experience for each member of the audience. Is there a reason why you wanted to make such affecting work for Sydney?

ATWhen I first spoke with BoS Artistic Director Mami Kataoka about being involved with the Biennale I immediately began to read many books about the history of Sydney and Australia. What struck me was that Sydney has such a rich migrant history. When I visited in 2016 I saw many people from different cultures living together in one city; it really is multicultural. In Parramatta I heard so many different languages being spoken and I loved the atmosphere—the mosque near the city, the Vietnamese food, the Cantonese chatter. This impression of Sydney as a gathering place of migrants made me think about the origins of Kabuki theatre.

Kabuki theatre is a very powerful art form. Japanese people are very proud of Kabuki, believing that it originated in the 17th century on the dry riverbeds near the shrine of Izumo, when prostitute Izumo no Okuni, together with other women, began dancing and performing in a new and innovative manner that, over time, developed into the highly stylized Kabuki we know today. This is widely accepted in Japan as the origin of Kabuki, however, there is an alternate history that traces Kabuki not to Japan, but Korea.

In this alternative legend Kabuki began in the late 16th century under the reign of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. During this period Japan attempted to conquer Korea and while they failed in their mission, they did return with new skills and technologies. It was during this time that Korean ceramics first made their way to Japan, as well as songs, dances and fabrics. But the Japanese did not just bring back objects; they also returned with highly trained Korean craftspeople. In Japan these people became oddities, living on the fringes of society and supplying bespoke skills for growing towns and cities. Separated from their families and homeland, they became increasingly frustrated and angry. Against the odds, they found a commonality with many of the young Japanese men who had originally removed them from their homes in Korea. Most of these men were the youngest sons of poor farmers who held little value to society and, having failed to win the war, they returned home not to jubilation but to be ostracised. Together with the Korean community, they invented dances and songs that connected them to their lost lives and, with growing confidence, they began parading on the street with stylised makeup, seeking to appeal to the community that shunned them. This new form of performance became known as Kabuki.

MTSo these dances and songs were born from this experience of trauma and a need to express anguish?

ATYes. They went to cities, villages and towns but were not accepted into communities. They eventually settled by a river outside a city where they played Kabuki theatre, afterwards called Kawara Kojiki, which translates as 'beggar on riverside'. Here on the river they held performances and people from the city would come and pay to watch the performances. This origin story of Kabuki theatre places the song and the story of migrants at its core.

MTDid it become a place of cultural exchange?

ATYes, the highly stylised performance highlighted the anguish of its participants, enabling them to appeal to their audience and communicate their situation. I participated in a workshop with a very famous Kabuki researcher and he told us this origin story. It is a forbidden story.

MTSo you can't find it anywhere?

ATYes, he did write it in some of his essays, but indirectly. If he wrote this story down more clearly it could change ideas about Kabuki, giving the practice so much more power. It would be recognised for its political and social activist roots, rather than be seen purely as entertainment.

MTI understand that this origin story could shift understandings of the foundations of Kabuki theatre, but it also speaks to how theatre can facilitate communication and engagement between different cultures and classes and help foster empathy.

ATThis is why I wanted to use the power of Kabuki theatre here in Sydney to capture emotions and to create a space where many different people from all over the city can share their story. The building of the hanamichi stage in Sydney's town hall was significant, as the building is a gathering place and becomes a place where people who have travelled from near and far can sing their songs. That is why I have named it Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Theatre.

MTWe are delighted to be showing this work at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art as part of BoS, because the building that houses the gallery is also an historic gathering place. It was built between 1893-95 to formalise offices for the local market. The land had always been a gathering place on the banks of Tumbalong—now known as Darling Harbour—for the Gadigal people of the Eora nation who met in this area to search for and share seafood. With the arrival of European occupiers, the area transformed into working wharves—a place of exchange and trade. By the early 20th century the area became not only a large market area but also the centre of Sydney's Chinese population. For over a hundred years people have congregated around this building to exchange, to share and to learn. You can just imagine the makeshift canvas awnings out the back where hundreds of market gardeners sold their goods; in some way this building has fed Sydney.

ATReally? That is wonderful.

MTWhen Mami Kataoka began to talk about developing your work for the BoS I thought how perfect this work is for 4A because of the building's history. Many of the participants in the video spoke about songs they wanted to sing; songs that aren't written down which belong instead to complex oral histories. These songs are connections to ancestors, to memories and to places and they wanted to ensure that by sharing these songs, they would still remain intimate and powerful. For many of the singers, their ancestors are still here, among us, and through the gesture of song they are once again connected.

ATI have also heard that there is a ghost here in this building.

MTYes, I think it is friendly though.

ATI like this idea a lot, as I think this work is not just for the living but is also for the dead. That these songs are intergenerational, that they are for ancestors and speak across time and space. I hope that the ghost likes the show. I hope that.—[O]

–Our Songs—Sydney Kabuki Project (2018), was commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Neilson Foundation and generous assistance from the Japan Foundation; the Australia-Japan Foundation of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; and Mami Kataoka.