Barbara Kasten: Out of the Box

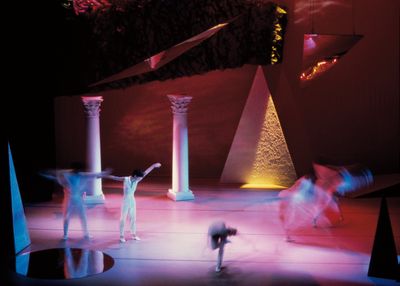

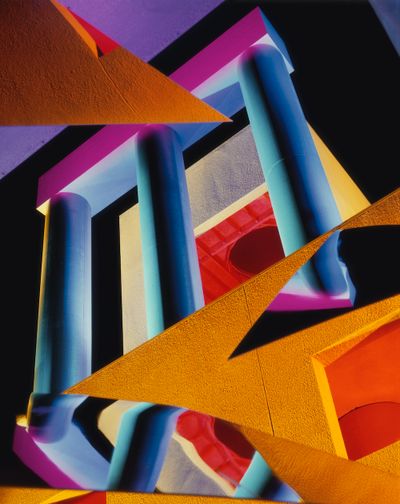

Barbara Kasten. Exhibition view: Parallels, Philara Collection, Düsseldorf (2 February–18 March 2018). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Susanne Diesner.

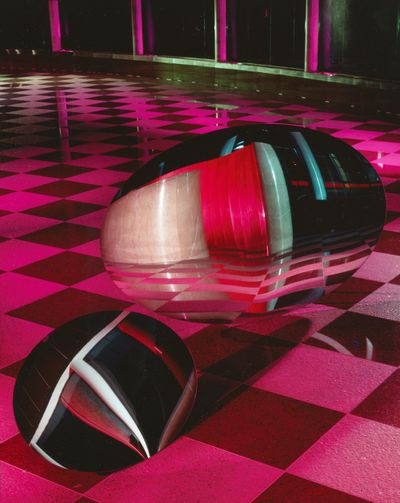

Barbara Kasten. Exhibition view: Parallels, Philara Collection, Düsseldorf (2 February–18 March 2018). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Susanne Diesner.

When Barbara Kasten: Stages opened in 2015 at the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, it was noted how overdue this first major museum survey was.

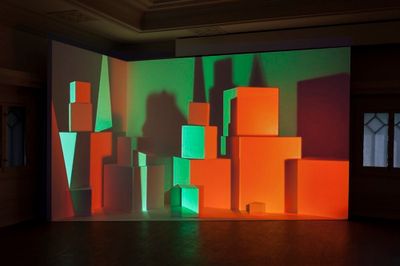

The show unfolded five impressive decades of Kasten's practice, from early 1970s sculptures handwoven from heavy ropes sourced from the ports of Gdańsk, the 'Photogenic Paintings' (1974–1976) photograms that represent her first photographic works, to Axis (2015), a 30-foot-high site-specific video installation that projected spinning shapes on the corner walls of a spacious gallery. Five years later, Barbara Kasten: Works at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg (21 March–8 November 2020) marks Kasten's first museum exhibition in Europe.

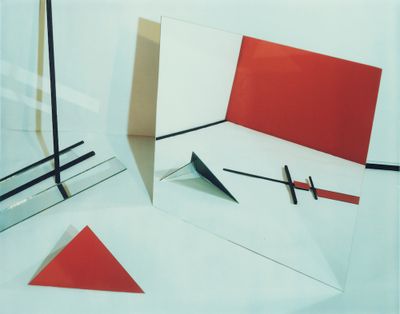

Some of Kasten's most recognisable images come from the 'Constructs' (1979–1986) series, which were created by building compositions in studio using materials like mirrors, architectural glass blocks, and an array of cones, cubes, and spheres. The arrangement would fit into the view of a set-up camera, and once all components were balanced in place (nothing was ever stuck down), lighting (plus gels and screens) activated shadows, highlights, reflections, and colours.

Caught on film are rich geometric abstractions and surreal dreamscapes built from intersecting perspectives and dimensions. Construct XI A (1981) shows a mirror with a circle cut out of it propped up by black trestle frame, its reflection cut up by two parallel mirrors laid out in front of it; while Construct NYC 12 (1984) feels like a de Chirico-meets-Sottsass acid trip: a landscape bathed in blood orange, acid green, and fuchsia shades, in which a Grecian column lies in front of an elegant arch, before which an ornate, black corbel rests on a white cube sitting on a flat black ladder.

The results are stunning and ahead of their time: images conjuring digital effects with analogue means, blending influences of the Bauhaus, in particular the photographic experiments of László Moholy-Nagy and the stage designs of Oskar Schlemmer, and Russian constructivism—think Lissitzky, Kandinsky, Popova—with an utterly contemporary tone, both in terms of the digitised 21st century and the time when Kasten developed the work.

Having lived in California in the 1960s and 70s, she cites West Coast minimalism, Finish Fetish, and Light and Space as influences: in particular James Turrell's projections, Craig Kauffman's and Helen Pashgian's experiments with plastic, John McCracken's finished surfaces, not to mention the paintings of Agnes Martin and the colour field painters. 'I felt free to incorporate any of these concepts into my thinking', Kasten notes on her development, having taken only one photography class at college. 'I wasn't breaking rules; I was actually making up my own.'

What came next was even more remarkable. In 1986, Kasten produced a series of images to accompany a Vanity Fair article on the entrance lobbies of New York's postmodern structures. With a professional cinematic lighting crew, she staged night-long shoots in spaces like the World Financial Center, where a circular mirror capturing a decorative ceiling appears like a ball in Architectural Site 6, July 14, 1986 (1986). Pre-planned sets with mirrors and powerful lighting rendered each space unsettled, and the series continued to develop beyond NYC and the Vanity Fair commission.

Architectural Site 17, August 29, 1988 (1988) shows an interior view of the Richard Meier-designed High Museum of Art in Atlanta lit up in hot pink, yellow, and Prussian blue, its features rendered into multi-dimensional shapes and lines. Cutting across the scene, a triangular mirror appears like a window thanks to one sculpture's reflection: a woman seemingly transfixed by the drama.

'Architecture has always been with me, which is understandable because of my love of geometric forms', Kasten has said. This geometry feeds into a practice that integrates photography with other disciplines so that it becomes something else altogether, like sculpture, installation, and painting, whose concerns deeply inform Kasten's approach.

The interdisciplinarity of the Bauhaus runs through Kasten's investigations. In 1985, Kasten collaborated with choreographer Margaret Jenkins to design the sets, costumes, and work on lighting design for Inside/Outside: Stages of Light. More recently, she has explored the spatial possibilities of video. In REMIX (2011), shown at Applied Art in Chicago in 2011, light becomes the main performer as it moves through space and surface like a dancer—reflective of an ongoing focus on light and shadow that continues in her photographs, with the 'Studio Constructs' series (2007–ongoing) distilled by an absence of colour.

In this conversation, Kasten looks at the development of her practice in light of her recent survey shows, discussing the works that have defined her career, the perspectives that constrain it, and projects that have not been widely seen by the public.

SBWorks at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg is your first museum show in Europe, a milestone that connects with your first museum survey at ICA Philadelphia in 2015. What impact have these shows had on you?

BKThe ICA show was definitely a game changer for me, for so many reasons. By then I was already in my seventies and past that middle point—not young enough to be discovered and not old enough to have attained some recognition, but at least old enough for people to notice that I'd been around for a while!

I don't really think of my work as a photographic abstraction. Of course, they're photographs, and the work appears abstract, but if you think of it in terms of photographic abstraction, it does not rely on any properties of the photograph.

From the very beginning, I straddled two worlds, with galleries that were exclusively focused on photography, and those that focused on contemporary art, like John Weber Gallery, who was an icon in the art world in the sixties and seventies. This led to an interesting mix, because I had already had exposure through the photo world, which led to my being framed by that discipline and an introduction to the art world by association with a well-known art gallery.

The ICA show released images and concepts that created an overview of my work beyond the photograph and within a museum context. Ever since then, the perception of my work has expanded because of the young people who saw my show. They had, I think, a different take on what photography could be. They came through an education system that explored photography in a totally different way than the photographers from a generation before. I never studied photography, so I wasn't caught in the trap either, but the perspective often limits my practice.

SBHow would you describe the perspective that limits your work?

BKIt's always seen as being about photography, but it's really not about photography per se. Certainly it began as a photographic image, but the purpose was never to explore photography. I think it was easier for people to identify me as a photographer because the photograph was evident. If I had been in different circles, I might have been thought of as a conceptual artist who used photography, because after all, what I was examining was not much different than artists working with light and how it reflects off materials.

However, I was never included in that realm at that time. There are many factors that contributed to this, including the way photography is taught. It's also departmentalised in institutions, both educational and in the museum, which all come with particular restrictions, including budgets. That division seems to work itself into everything: the market, the exposure, the perception of the artist as one thing or another, even if people are crossing boundaries all the time.

It's always interesting to me when I'm included in a museum collection that doesn't have a photography department. Within my practice, I do not research photographic process, photographic history, or anything directly connected to photography. More recently, boundaries have opened up, and that makes a difference. I have to attribute that to the openness of a different generation and a different mindset about art that somehow goes back to the Bauhaus. It's like we've gone through phases and have come back to the essentials.

SBI guess, in a way, you were trying to open up spaces of representation, but always found yourself being put back inside the camera you were working out of.

BKExactly. That's really true. Most of what I do is in front of the camera, and in a way, the camera is there to document what I do. In a lot of ways, I was fighting the credentials of a photograph and playing on the illusion. I think from the very onset, my goals were not all aligned with photography.

Photographic acceptance now is not as narrow as it was in the sixties and seventies. In art circles, photography can have a wide range of expressions and ways of working. Even now though, I still have friends who know me and my work really well, and they still ask me to recommend cameras, and I'm like, I don't know cameras except the one I use, which is basically a box camera with a large glass viewing back!

From the very beginning, I straddled two worlds, with galleries that were exclusively focused on photography, and those that focused on contemporary art...

SBIt's interesting how your resistance towards being framed by photography has become part of the practice. The ICA show and the impact it had on younger artists seems to have bolstered this.

BKIt was the right time in my life and the right moment to be examined by the right kind of people who had open ideas. It was actually a young curator, Alex Klein, who made the ICA show happen. She had come across my work when she was researching for her master's degree in art at UCLA.

Afterwards, when she worked with LACMA's photo department, she invited me to do a lecture. She later took a position at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. When she had an opportunity to curate her first show there, she thought of me. That provided the support of people who didn't have the West Coast historical perspective of photography as still life and examinations of form, or of New York, where it was all documentary and street photography. Alex had a much broader perspective of what photography could be.

I'm now working on an exhibition for the Aspen Art Museum to open in October that will only show my video sculptures and three-dimensional pieces that I have developed since Stages, the ICA exhibit. In addition, a book is in the works, featuring the sculptures and video installation that will change the view of my work even more.

SBRight, because as much as the ICA show was a survey, it was also a point of departure. You created the site-specific video installation Axis, which you have said marked a new direction, and then created Scenario when you staged the show at the Graham Foundation that year, which was the first time you projected video onto objects.

BKIt really was a new direction for me, and when the ICA show travelled to the Graham Foundation here in Chicago, Axis was no longer viable for the Graham Foundation since it is an old mansion with beautiful architectural detail, but without a 30-foot-high corner. That exhibition took place in conjunction with the Chicago Architecture Biennial and they wanted an installation piece, so they gave me the opportunity to do something new. Each site invites something different.

My ICA exhibition was also shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles. There, I installed Sideways Corner (2016), a video made earlier that year and reconfigured it into a skylight well. So I had three new works that I would not normally have had the opportunity to present, especially in that short amount of time. Everybody was interested in showing a video work and I was eager to make something new. The timing worked out.

SBThinking about surveys as turning points, did your Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg show mark a point of departure in the way your ICA show spurred a new trajectory?

BKYes, I did a freestanding outdoor sculpture. I had made freestanding sculptures before—for a show at Philara in Dusseldorf, and at Bortolami Gallery in New York, and the Crown Hall project in Chicago. These were all freestanding works with moveable elements, based on an architectural concept. None of these pieces were permanently held in place. It was about balance and using common objects in different ways than intended, which always creeps into the material aspect of the work I do.

I'm not examining anything except those two essentials of making a photograph: there has to be an object, and there has to be light.

At Wolfsburg, I discovered they were making the innards for a wall system. Since they have a big open space, they're always putting up walls, and they developed a system that was so successful that they provide wall structures and components to build walls for museums all over the world. I was fascinated. They took me to the factory where they make these walls—they had prototypes with museum names written on their sides—and I asked if I could use them. Since the show had a more traditional installation, this allowed me to be experimental. I put together a model and the next time I went back, I went to the factory and we assembled a sculpture.

Because the exhibition room was very long and narrow, the sculpture didn't sit well inside. We looked around and the balcony of the building, which is kind of a bizarre structure in itself, was ideal. I don't know what's going to happen to it once the show closes, but it doesn't actually matter; it was meant to be particular to that space.

SBThere are echoes of the 'Constructs' and 'Architectural Sites' series here: a hanging balance contained by a precarious construction, in which architectural space becomes a frame for an accumulation of gestures. The different elements document a reach for this moment of equilibrium: when things come together.

BKRight. And if anything, that's the eureka moment. The light hits in a certain way. For this work and the one at Crown Hall, I actually used the natural light. There was no spotlighting at all. It's like using the basic elements of photography but applying them to different media, finding different ways of putting things together and examining them. It doesn't always have to end up on a flat surface.

It's not like I know what I'm after when I'm in the process of making. I'm just after something that's only there at a particular moment. It's not a didactic statement but more of a situation that asks: 'What do you see?'

SBThis makes me think about the refraction of light and how it has developed from your 'Constructs' through to the later 'Studio Constructs' series. You have talked about being less concerned with the state of media—for example, photography—than with the possibilities of different materials, which become conduits for the main element in your work, which is light and what it does. In that sense, light and shadow become the media, the material, the subject, and representation—in short, the object.

Thinking about the camera and the frame, there is a real decentring happening in these compositions, like you're refracting light to open up representational space.

BKYes, but it is not a photograph of a sculpture. It seems people want to make it the subject, but it's not what I'm photographing. I mean, there is a photograph and there is a sculpture together, but it's about seeing the material differently. The light creates shadow and that becomes form too. If it's moving like in a video, it changes forms; when you add additional information, it can no longer be identified as one thing. It becomes something else.

SBI always imagine your compositions teetering in space, as if the photograph is the documentation of a performance.

BKThat's true, but people sometimes want a more concrete definition of things! They don't want to add their own imagination to it.

SBHow does this relate to that question you have posed in past interviews, about whether a complete photographic abstraction is possible?

BKI don't really think of my work as a photographic abstraction. Of course, they're photographs, and the work appears abstract, but if you think of it in terms of photographic abstraction, it does not rely on any properties of the photograph. I'm not examining any photographic process. I'm not examining anything except those two essentials of making a photograph: there has to be an object, and there has to be light. I use light to turn objects into ephemeral objects. It's also based on the recognition of the material and expanding its qualities to change its identity. This is important, because it's not just about shape and a form, but about the material as an object.

The condition of putting all that together is more like what a painter would do than a photographer. It's interesting to me because I could paint shapes with textures, but they're not real shapes in real time as it is in a photograph. I'm really basing my thinking on what is happening in front of the frame, rather than within it.

SBYou actually studied painting first at the University of Arizona, where you graduated in 1959. Could you talk about the trajectory that led you from there to Germany, where you lived for some time?

BKAfter graduating I worked in San Francisco in fashion making window displays, which is very related to the way I make installations to photograph. After a couple of years, I didn't know what I wanted to do, so I went back to school and got a teaching degree for secondary school. I did that for one semester and nearly went crazy. I had a friend who had a U.S. civil service government job, which appealed to me. It took me to Europe for two years, where I worked on an army base as a civil employee, managing a community centre for soldiers and their families—everything from staging entertainment to organising arts and crafts workshops.

This was in the sixties. I was painting at the same time and travelled a lot, so I had exposure to different exhibitions and architecture. It was my first time out of the States and it opened up my world.

When I came back to the U.S. and applied to grad school, I was rejected from the painting programme. I had seen an exhibition in Europe that presented tapestries in an innovative way, which sparked my interest in textiles. I thought it related in form and texture to the painting I was doing at the time, but I didn't know anything about weaving; so I apprenticed myself to a weaver and made a portfolio that I submitted as my graduate application to San Francisco State University. When I enrolled as a student, the Vietnam demonstrations happened, so I never actually went to that school. I knew about California College of Arts and Crafts and of a teacher there, but it was expensive, so I applied for a scholarship. It was there that I studied with Trude Guermonprez, a Bauhaus-trained artist who became my mentor and connection with Bauhaus ideas.

One thing leads to another. Curiosity pushes the desire to know more about the next step, which leads to more information, which leads to thenext step.

I did take one photography class during this time. The teacher, a well-known California photographer, curator, and historian became my future husband. A few years later, he did a show of Moholy-Nagy photograms and photography, so I had first-hand experience of Moholy-Nagy's work. Bauhaus ideologies, histories, and experiments in photography and light—this was what interested me about photography.

SBHow do your early anthropomorphic fibre sculptures fit into this trajectory? I understand you developed these on a Fulbright fellowship in Poland, studying with Magdalena Abakanowicz.

BKI developed a correspondence with Magdalena Abakanowicz when I curated an exhibition at California College of Arts and Crafts as my graduate thesis of the sculptural fibre art that was becoming accepted as an art form. I received a Fulbright-Hays fellowship to study with her in Poland in 1972.

When I returned to California, because of my background and my degree, I could teach textile design, but I wanted to teach it as sculpture, expanding the technique of flat, woven patterns. I wanted to make three-dimensional forms and I found fibreglass window screening mesh, which helped me demonstrate the possibilities. It was also the first material I used my early photograms in cyanotype. This all relates to what I've been doing for years: taking a material and pushing its boundaries; to have material do something it was not meant to do.

Although I didn't need to use a darkroom to create photograms, I had access to one because of my ex-husband. I made life-sized photograms—I prefer to work in large-scale—either working outdoors with cyanotypes or in the darkroom creating photograms with geometric shapes. Then I was given the new instant Polaroid film and I didn't need the darkroom—I could do the same sort of arrangements of objects in front of a camera, so I borrowed an eight by ten view camera started working with a camera. That was 1982.

SBWhat was driving you at that time? What kept you reaching for this path of investigation that somehow clicked?

BKOne thing leads to another. Curiosity pushes the desire to know more about the next step, which leads to more information, which leads to the next step. Then there is tenacity and determination; all of those things that make up a personality.

I was also older. I was in my thirties. I knew that I had found something that I could do. The teaching was the enabler, in a way. However, I didn't really want to end up teaching, because I could see the pitfalls of being so involved in your teaching that you lose sight of your own interests. There was also a feminist aspect to this, because it was a time when women were proving themselves, and I was not going to be told what I could do by anybody, especially by a traditional patriarchal society.

SBOn that note, how did you decide to become artist?

BKI don't think I decided, I think it just happened. That's what I was doing. It just developed into the goal, but not with any purposeful direction; it was just something I felt I could do well and liked doing. That's important: to enjoy what you're doing but also to sustain yourself doing it. People don't realise that it's a lot of work to be an artist; it is not easy!

SBWere there any moments when your conviction faltered?

BKI knew I was not going to fail in pursuing something that interested me. The only time I think that I had to make a choice was when I received a Guggenheim grant, which in itself was great, but at the time I had a teaching position in Southern California. The grant gave me the chance to take a year-long sabbatical. I went to New York and made many photographs in the 24x20 studio of Polaroid.

When the year was up, I was expected to go back to teaching or pay back the sabbatical salary I was given. I felt I would be giving up everything I'd achieved, because teaching wasn't my main goal. I was fortunate that I could sell enough work to live in New York, so I paid the money back, and that was when I knew I was committed to this. I stayed in New York for almost 20 years.

SBThis would have been in the eighties, when the 'Architectural Sites' series came about.

BKYes, and I was freshly divorced and free to express myself. I come from a generation whose parents thought that you should support the man in your life, and I did choose a very interesting guy to live with, but I didn't like being in that secondary role. And even though he didn't demand it, I couldn't figure out how to do both. So I made a decision that was solely based on what I wanted rather than on being a partner in a situation where we both pursued something together.

Bauhaus ideologies, histories, and experiments in photography and light—this was what interested me about photography.

SBThat really gives another reading to the 'Architectural Sites' images, because this was such an ambitious project and it shows. Part of it must have been driven by the challenges you were up against.

BKIn terms of how determined I was, you can get a sense of this in the scale of the production. I had many roles in the process. I was director, promoter, fundraiser. I made some photo trades with the institutions that I wanted to photograph once I didn't have the Vanity Fair commission. I had to find a way to continue because I knew it was something I wanted to do.

But they were not accepted at the time. When I showed them, the critics thought they were garishly coloured. Why was I doing this in that space? Why weren't they more political? They were political, but they weren't overtly so. This was also a time when there had to be theory behind the work. But what I found really interesting was what was happening in architecture and how that reflected the fabric of society, because all this architecture was so grandiose.

SBHow does 'Architectural Sites' relate to lesser-known projects like the 'Pueblo' series?

BKI'm glad you brought these up, because those works have not had recent exposure and I hope that changes. What seems to have happened is that, in a very practical way, I've been accepted as an artist—just like I was accepted as a photographer—but am still kept within the framework of abstraction, which is fine, but those photographs from the nineties are a different kind of examination for me.

If anything, this was a soul-searching time; I was thinking about where to go after 'Constructs' and 'Architectural Sites', and these works were like stepping stones back to what I felt was important, which was my experiences in the Southwest. I grew up in Chicago, and when I moved to the Southwest with my parents, it changed my life. I was fascinated with the history and its native American cultures that I respect and feel really drawn to. So I went back to what I knew—to try and find grounding in an examination of my own.

The pueblos were ancient sites, and I used the same techniques from the 'Architectural Sites' series and staged the images the same way, just in a different context. Then I took the series to Arizona and Spain, where I examined the history of Tarragona. I was then offered a residency in Brittany, where there are dolmen and menhir: megalithic structures related to birth and death, and I could see a connection with the Southwest and Tarragona. These were real photographic shoots: I got up at the crack of dawn with an assistant and we crossed fields and photographed these amazing places. It was very cathartic for me.

In the 1990s, I had the chance to learn about digital technology with Apple. They were sponsored programmes to teach artists, architects, and designers about the new Adobe software. I started making digital murals. I have huge murals on canvas that nobody has seen! I'm looking at one right now on my wall: it's not quite a mural, but it was a digital production printing process on canvas and it's eight feet long.

The one mural I made about Tarragona is 40 feet long; others are 20 to 30 feet long. They all relate to the roots and history of human beings through the examination of architecture. I was looking at the architecture of the past as a reference to architecture of today. I also photographed and made photograms of artifacts of various cultures. I liked the idea of working with museum collections. I did a photographic series, 'Tanagra Goddess', using Cornell University's teaching collection of goddess statuettes found in ancient graves of Greek women.

Abstraction is not just about moving around forms and colour and shapes and geometry. It's about creating the conditions to be open and receptive to ideas.

SBGoing back to what you said about your work not being overtly political, which relates to what you've said about abstraction being a political tool. Could you elaborate?

BKI think it's related to the Bauhaus philosophy of examining how experimentation can change attitudes and ideas. Abstraction is not just about moving around forms and colour and shapes and geometry. It's about creating the conditions to be open and receptive to ideas. To see other possibilities, to see what other people have to offer, to see how it can be incorporated in your life, and to give it a chance, instead of just dismissing it as pure form. It's so much more than that. I think abstraction relies on that essential provocation: what can happen when you look at something that you don't understand and try to make sense of? That's the political side, which might not be obvious.

SBThis returns to refraction. As with your constructs, there are a lot of perspectives intersecting in those 'Architectural Sites' pictures, which speaks to the complexity in your work more generally. Even with your early textile pieces—it is the fabric mesh that resonates.

BKExactly. You know, I love Agnes Martin, and though my work might not draw an immediate visual connection to her work, there are similarities relating to structure, repetition, thought, and minute differences in colour and form—and it's all part of the process.

SBWith that in mind, what have been the most profound lessons that you've learned as an artist so far?

BKI think it comes down to examining yourself and knowing what it is that you can do well and what interests you. It might sound obvious, but you do have to believe in yourself. You also have to be open to see when you're not right.

Maybe there's another way to do things, and maybe you need to examine more issues before you go in one direction. It's a continuous exploration of who we are, trying to figure out life.—[O]