Curator Margot Norton on Wangechi Mutu’s Arresting Art

Exhibition view: Wangechi Mutu, Intertwined, New Museum, New York (2 March–4 June 2023). Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Exhibition view: Wangechi Mutu, Intertwined, New Museum, New York (2 March–4 June 2023). Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

The subject of a major survey at the New Museum in New York, Wangechi Mutu has committed her life and work to telling moving stories about women who look like her, yet seldom have their histories heard.

Exploring issues of identity, colonialism, feminism, Afrofuturism, and globalisation, Mutu filters these concerns through a spiritual relationship to nature.

'My obsession with the Black female body is a kind of obsession with myself navigating the world in a very sort of processed form,' the Nairobi and New York-based artist shared in a 2015 video for the Louisiana Channel. 'I don't do biographical or self-portrait work but I'm questioning and sort of resolving the issue of our invisibility by making the work.'

Born in 1972 in Nairobi, Kenya, and raised by her grandmother and mother, who was a midwife and nurse, Mutu received a middle-class education at a Catholic girls' school in her hometown, which was still dominated by British culture. She left Kenya in 1989 to study in Wales before journeying to New York, where she studied Anthropology and Fine Arts at The New School for Social Research and Parsons School of Design.

Earning a BFA from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 1996, Mutu exhibited at the 1997 Johannesburg Biennale organised by Okwui Enwezor, and was the subject of a solo show curated by Derrick Adams (now a successful artist in his own right) at Rush Arts Gallery, an Afrocentric art centre in New York, all before completing her MFA at Yale School of Art in 2000.

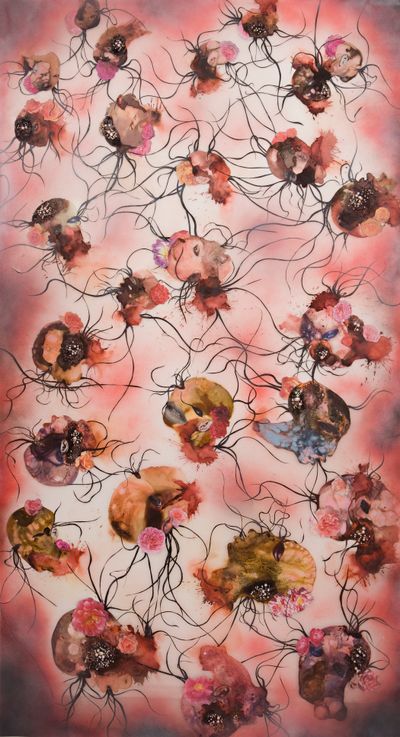

While known for her sculptures, Mutu initially made her mark as an emerging artist through her evolving series of hybrid collage paintings of anthropomorphic women. These collages mix abstract washes of ink and watercolour, as well as beads and shells, with cut-out images of body parts, machines, and flowers from fashion, medical, and porn publications.

Exhibiting widely in New York before taking the world by storm, Mutu had a breakthrough moment with her compelling collage painting Yo Mama (2003), which was commissioned by the New Museum for the Black President: The Art and Legacy of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti exhibition in 2003.

Coming full circle, Mutu's current survey at the New Museum, Intertwined (2 March–4 June 2023), is co-curated by Margot Norton and Vivian Crockett with Ian Wallace. The exhibition highlights her evolution from a burgeoning sculptor to a mixed-media collagist and filmmaker, and her return to large-scale sculpture upon re-settling in Nairobi in 2015.

In the following conversation, Margot Norton, the New Museum's Allen and Lola Goldring Senior Curator, discusses the 30-year arc of the artist's arresting art and the curatorial selection of some 100 works in the engaging exhibition, which encompasses the majority of the seven-storey museum.

PLWhen did you and Vivian begin work on this exhibition and why did you believe it was important to highlight Wangechi Mutu's work at this time?

MNThe exhibition began about one-and-a-half years ago, but Wangechi Mutu is an artist both Vivian Crockett and I have admired and have been wanting to work with on a major exhibition for many years.

Her work has been seen in New York at various points throughout her career, but we felt that there was an important opportunity to showcase the arc of her practice, starting with the sculptural work that she made as a student in the nineties and up until the present.

Wangechi Mutu's work links to histories of feminist art and expands upon them.

Throughout her career, there have been shifts as she has continued to experiment and push her work in different media, including collage, sculpture, performance, and film. We felt that bringing these works together would be important to seeing through-lines and connections between her bodies of work.

It was also important to highlight her work because so many artists today are working with natural materials, cyborgian creatures, and themes Wangechi explored for decades.

PLWhat role did the artist play in the selection of works on view?

MNIt was always a very close dialogue between Vivian, me, Wangechi, and her team. From the beginning of working on the exhibition to now, we worked collaboratively in terms of what works would be shown.

We did a lot of research together, highlighting which works would be essential to the exhibition. Some are quite iconic, while others have never been seen. Some are early works she's never shown, others are brand new.

PLThe show inhabits the whole museum, yet it's not being billed as a retrospective. Why did you decide to call it an exhibition rather than a survey or retrospective?

MNWe tend to not call our exhibitions retrospectives at the New Museum, but have called them 'introspectives' before. Our shows are not typically arranged strictly chronologically. Many artists circle back to various themes throughout their careers. It's interesting to see how they revisit and expand upon ideas in their work across time.

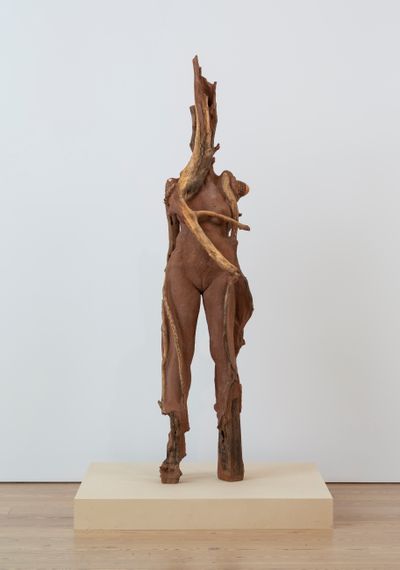

For example, on the third floor of the exhibition, the majority of works are sculptures Wangechi has been making since she moved back to Nairobi in 2015 and began to work with natural materials from the Kenyan landscape, such as soil and wood.

On the same floor, we've included a series of drawings from 2003 titled 'MUD'. These are collages of women sourced from pin-ups and pornography magazines that are covered with a paint that resembles mud. Interestingly, this idea of working with earth has been something Wangechi has been drawn to from early on in her career.

Other works on this floor, like Cutting (2004)—a performative video work of Wangechi repeatedly hitting a log with a machete—also circle back to these themes, but not necessarily in a neat linear progression.

PLThe artist's rarely seen sketchbook studies and early sculptural assemblages, which are still in her personal collection, seem to set the stage for what was to come.

Why did you believe it was important to feature these more intimate pieces in the show?

MNFollowing her move to Nairobi, Wangechi was included in the 2019 Whitney Biennial and first showed her sculptural works made with natural materials from the 'Sentinel' series and other works like Poems by my Great Grandmother I (2017).

We knew of her work in cut paper and experimental mixed-media collages, but were not familiar with Wangechi as a sculptor. Interestingly, she actually began her career as a sculptor. As a student, she was working out many of the themes that would recur in her more recent sculptures.

Methods of assemblage and collage run throughout her practice, including her work in animation and even her bronze sculptures. It's incredible how she's able to fluidly combine these hybrid forms and different materialities in any media.

When we saw images of the early sculptures, which date back to 1997, we saw that she was creating assemblages of found materials such as cowry shells, liquor bottles, and objects bound and fused with tar and wax. At the time, she was looking at artists who worked with found material and sculptural assemblage on the streets of New York City.

It's fascinating to see how she developed an interest in these hybrid amalgamations of material—from cut paper, watercolour, and ink to bones, stones, soil, and wood. Her work in sculpture is very much connected to her two-dimensional work and her work in animation and film.

PLIt was a real surprise to see how related these sculptures are to her use of collage. These works are part of the second-floor gallery presentation, which is primarily focused on the artist's hybrid collage paintings on paper.

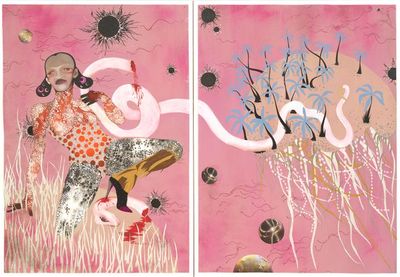

Mutu's large-scale diptych Yo Mama, which was first exhibited at the New Museum in 2003 and is now in The Museum of Modern Art's collection, is featured in this mix. Do you see it as a seminal piece in the artist's oeuvre?

MNIt definitely feels like a central piece in the show, both in terms of how she pushed herself in scale and subject matter, and introduced the diptych format she would continue to work with in her later large-scale collages.

Yo Mama is a work on paper but right after she made it, she participated in The Studio Museum in Harlem's Artist-in-Residence programme and began to experiment with Mylar—a polyester film material that became a staple of her practice.

The work has a really beautiful narrative to it. Wangechi was commissioned to make a work about the legacy of Fela Kuti, who was the subject of the Black President exhibition at the New Museum in 2003, curated by Trevor Schoonmaker.

For her commission, she focused on Kuti's mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, who was an activist and advocate for women's rights and highly influential on Fela's career and activism.

Yo Mama is an incredible portrait of a magnificently powerful woman who was also subject to violence, which led to her death after being thrown out of a building during a raid. Wangechi created this fantastical and beautiful homage to her with this piece.

Around that period—2003, 2004—she began making these beautiful, kaleidoscopic marbled textures with ink and watercolour and these fluid combinations of materials in her collages. This piece really pushed her work in that direction.

PLHow do you think Mutu's method of collaging mediated imagery into her paintings contributes to the visual vocabulary of feminist art?

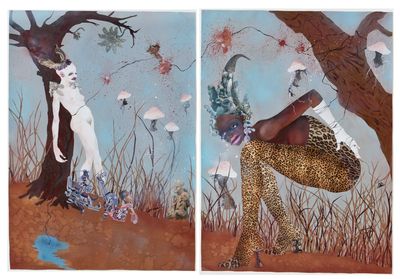

MNHer work links to histories of feminist art and expands upon them. To make her collages, for example, she took images from fashion magazines and pornography, as well as images from National Geographic and primitivising or exoticising images of women, and created new contexts or futures for them through recombination.

She also brings a feminist perspective into subjects such as pathology and historical violence and their impact on women in series such as 'Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors' (2004–2005).

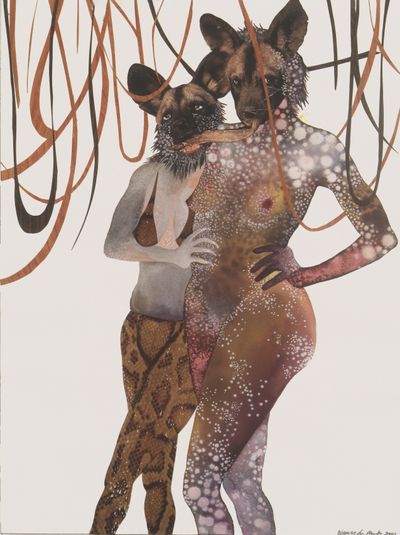

PLThe title of the exhibition, Intertwined, comes from another 2003 collage painting depicting two embracing femmes with animal heads. Did you see this piece as having an overarching characteristic of her work and for the show?

MNWe felt that so much within that work resonates thematically throughout her practice. The collage depicts two painted dogs fighting over a scrap of meat taken from a National Geographic. She transformed them into majestic, powerful figures of women who seem to gaze directly at viewers.

They are also intertwined with each other, botanical vines come down and snake around their bodies. It's a small but mighty work, and in it we saw how the theme of interconnection resonates throughout her work and speaks to our reciprocal relationships with one another, the earth, and all living beings with whom we share our planet.

While she's taking these objects from various sources, she's never just quoting the sources, but developing a future or world for them.

The work also connects to more recent works she's made that deal with themes of doubling and hybridity, such as In Two Canoe (2022) in our lobby gallery, which similarly depicts two figures intertwined with these mangrove roots that seem to extend into the floor.

With that work and others, there is a way that her work pushes up against the architecture of the museum—and we see this in her early collage works as well, which almost exceed the bounds of their frames.

PLThere are definitely precedents to combining painting with collage—artists like Richard Hamilton, Robert Rauschenberg, and Tom Wesselmann come to mind—but her way of working with photographic imagery culled from magazines and her material sensibility seem different.

What does Mutu add to this way of working that's uniquely identifiable as her style?

MNI've always been fascinated by the intuitive sense of fluidity between Wangechi's forms. In many of her collages, you can't quite tell where one collaged or painted element ends and the other begins.

Yet within her works, you will often find playfulness and even humour, which reflect this complexity of being human.

She also transforms her images or objects; you can sometimes forget about their original context, and then come to notice it again on closer inspection. There is this continuous push and pull between the specificity of her references and the expansiveness of her imagination.

While she's taking these objects from various sources, she's never just quoting the sources, but developing a future or world for them that doesn't yet exist. She makes them her own.

PLI've been interviewing and writing about a number of African artists over the past several years, and covering African American artists for the past 20 years, which has led me to find overlapping yet distinctly different approaches to their cultural concepts.

How do you interpret the parallels and differences in their positions?

MNWangechi has a unique position in relation to this because she was raised in Nairobi, moved to New York, where she lived for over 20 years, and then returned to Nairobi more recently.

She described it really beautifully in a quote from Aruna D'Souza's profile on her in The New York Times, speaking about having roots in multiple places, almost like the mangrove roots in works like In Two Canoe. She is an African artist, but very much a New York artist as well. It's difficult to categorise her in terms of one place or another. She is both.

PLDo you think that being born in Kenya, where traditional spiritual practices precede colonialism, but being educated in a Catholic school as a child played a part in the development of her allegories? Like how Santería in Cuba and Vodou in Haiti have impacted the thinking in both places.

MNThere's a beautiful sculpture in the exhibition from 1997 called Maria, which holds a lot of the cultural complexities you mention.

Wangechi was making the 'Bottle People' series at the time, which was included in her BFA thesis show at Cooper Union. They've been referred to as contemporary interpretations of nkisi nkondi [power figure] sculptures, but were also very much inspired by the sculptural assemblage work she saw in the streets of lower Manhattan at the time.

For this work, she took a doll's head that she found on New York City's streets, placed it on top of a small statue of the Virgin Mary, and bound it with string. There's a lot within this work that speaks to those themes.

These cultural and spiritual interconnections come up throughout the exhibition in her use of allegory and the ways that animal-humanoid creatures have figured in different mythologies across continents. There is specificity in her references, but also an expansive view of the ways that cultures are very much intertwined.

PLHer practice seems to be centred on Afrofuturism. In your interview for the catalogue, she says of collage: 'I was bringing together my past and present to formulate a sense of what my future would be.' Isn't that at the heart of Afrofuturism?

MNDefinitely. It's interesting to see how Afrofuturism has been a feature of her work since the beginning. She was always creating these cyborgian warrior femmes, which almost reach back into ancient or precolonial histories as they reach into the future.

PLI can see that in her early work, around when the term was first coined. Does the strength of her visual allegories come from the fact that they are both personal and universal?

MNDefinitely. She's interested in these allegorical references—the crocodile, fish-woman, or serpent-woman hybrid—and what they mean in specific cultures across the globe but her own imagination comes in there, too.

PLIn conversations related to her work, she often speaks about the stereotypical views of Black women and especially Black African women, and her desire to change those views through her art. Do you think she is succeeding in her pursuit?

MNI don't know if I can cite a specific example of what you mean by succeeding, but when I look at the figures in her work, I can see that many of them have been through trauma or violence—she doesn't shy away from difficult histories.

Yet within her works, you will often find playfulness and even humour, which reflect this complexity of being human—it's never all dark or light. These figures often feel confident and poised, and can transcend the ways they might have been represented in a magazine, for example, or the context they were found in.

PLI see this in the collages, in taking apart the imagery from pin-ups or pornography and exploding it on the surface of the collage painting.

I see it in Crocodylus (2020) too, her sculpture of a woman riding a crocodile, based on Jean-Paul Goude's photo of Naomi Campbell on the back of a crocodile. His image is much more sexualised, while Mutu's work depicts a woman of strength rather than an object of desire.

MNThat's a perfect example because she is taking this problematic image and transforming it into something that she would imagine it to be—the future she would build for it. In that piece, the figure is merged with the crocodile and becomes the crocodile. It's not about one thing overcoming or dominating the other. They are part of the same body.

PLThere's definitely a marriage of the two. Sculpture plays an equal role in Mutu's storytelling, particularly in her strong presentation of women. Did her return to sculpture grow out of the collage process, or from the installations that she created for the display of her collage paintings?

MNYou can see the influence of sculpture in her later collages such as Fallen Heads (2010), where images became increasingly sculptural and with these great textural combinations of glitter, soil, and pearls, which seem to almost reach outside the collage.

You can also see it in a painting we have on the third floor—The Storm (2012)—where she's created kaleidoscopic swirls of hair and thick accumulations of materials.

In the installation on the second floor, we combined sculptural work from her student days in the nineties with Moth Collection (2010). She describes in the catalogue interview how that piece came out of her need for the work to come alive and extend from the two-dimensional plane.

That led to works like Sleeping Serpent (2014), a large ceramic and stuffed-fabric sculpture on the third floor—up to the works with natural materials that she began making following her return to Kenya in 2015.

Even on the salon wall that we have on the second floor, you can see how her cut-paper collages became increasingly experimental and sculptural. By 2012, they really wanted to leap off the paper.

PLHer relationship to nature is visible in her collage paintings. Yet doubly discernible in her sculptures and films is her interest in nature and feminism.

This is held in the representation of a goddess—a guardian of the earth and all living things inhabiting it, especially mistreated and misunderstood women.

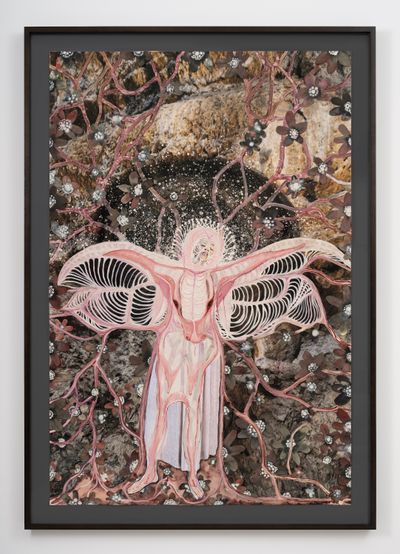

MNThese films—both her performance for the camera and animated works—are key in relation to this, and so related to her sculptural and collage-based works. In her films, she is often the protagonist and becomes a sculpture herself by performing repetitive tasks.

In Cleaning Earth (2006), she washes a strip of dirt floor; in Cutting, she chops wood with a machete; and in Eat Cake (2012), she eats a cake that resembles earth and wears these big, heeled shoes like many creatures in her collages. There's a simultaneous reverence and criticality in a lot of the works. She draws attention to constructs and at the same time, they become a reflection of viewers.

PLIt's a shocking image. How did her return to Kenya and building a big studio in Nairobi impact her work, particularly her sculpture?

MNShe was always fascinated with the soil there, which has this rich, reddish colour. When she moved there, her work exploded with the use of found materials such as tree branches, shells, or bones.

Similarly to the works on paper, where she would continually collect eyes, mouths, and limbs from different magazines, she would travel around the landscape and source different items. They are another recombination of materials and similarly to her collages, they hover between abstraction and the representation of humanoid forms.

PLHer use of mud, tree roots, and other items wouldn't have happened had she remained in upstate New York. There wouldn't have been the same type of emotional and rooted development in the work.

MNThey're very much about her relationship with the land there.

PLGoing back as a mature artist, she's able to then incorporate those things in such an intuitive way. Her titles seem to provide insight into the works and her state of mind when making them. How do these titles add to the work, whether it be descriptive or poetic?

MNThe titles are incredible, but not so specific that they give a straightforward narrative. Some are related to music and combine different references to pop culture or history. There's poetry in them and also humour. She gives hints with the title but doesn't give it all away.

PLYour show packs a powerful punch with the substantial presentation of early works on the second floor, and captures her incredible growth over the following years on the remaining exhibition floors up to seven, where just one sculpture is placed: Shavasana I (2019).

The sculpture depicts a figure in the yoga corpse pose covered by a palm frond mat. It's quite different from her more anthropomorphic works. What can you tell us about it?

MNShavasana I is the title of this piece and the name of the pose, which often comes at the end of a yoga practice when the body is resting. In Sanskrit, it means corpse pose.

In other works of hers, including Sleeping Heads (2006), she similarly explores this relationship between sleeping and death, and our relationship to how we might view a body lying down—the tension between it being a resting or dead body.

The mat covering the body is typically found in Kenya and other tropical places with palm fronds and is often woven by women. It's made using the same technique that's used for the bronze basket works on the fourth floor of the exhibition.

In a lot of her work, she gives a certain weight to the labour embedded in the materials and the relationship between craft and monumentality. We talked about how they're almost anti-monuments because they're sculpted in bronze—a material we associate with monuments—but instead, they're lying flat on the floor and at the scale of a human body.

The work is also a mirror that asks viewers how we might feel when we come upon a body lying down. Having this work in a room of its own is important in giving it space to resonate.

PLAs the corpse pose is meant to rejuvenate the body, mind, and spirit while reducing tension and stress, this piece almost seems like a self-portrait where the artist is summing up her work, taking a breath, and deciding what's next.

Is that a plausible reading?

MNIt could be. But even when she is dealing with this dark subject matter, there's always an element of humour that comes through—the heels and nail polish. It reminds us of what keeps us human.

PLSome 30 years into her practice, with around 20 years of continuous visibility of her work around the world, do you see Mutu as having an influence on younger artists?

MNFor sure. It has been illuminating to hear from so many artists about the influence of her work both in New York and at schools she attended, like Cooper Union, but also her influence on artists around the world.

We hope that the exhibition will provide the opportunity both for those familiar and unfamiliar with her practice to see the impact she has made and how many themes she addressed early on resonate so much today.

PLIt seems like by crossing the ocean, she's able to tie a lot of things together for a lot of people.

MNDefinitely. —[O]