Ellen Lesperance Merges Knitting With Paint to Extend Activist Archives

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

Ellen Lesperance. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Rose Dickson.

Ellen Lesperance. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Rose Dickson.

American artist Ellen Lesperance's engagement with activism informs a painting practice centred on attire worn by female demonstrators, cultural figures, and warriors, sourced from photographs and historical archives.

Born in Minneapolis in the United States in 1971, Lesperance is best known for gouache paintings that depict full-length knitted clothing worn by female protestors who sought to reach social and political objectives through non-violent direct action.

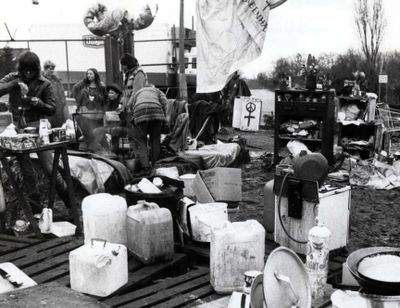

With equal dedication, Lesperance has been collecting images from the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, which was formed to protest the U.S. nuclear armament in Berkshire, England, enlisting over 30,000 members for over two decades.

Protestors at the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp engaged in non-violent direct action through knitting, wearing sweaters emblazoned with rainbows, peace signs, celestial skies, and battle axes, which inspired the initial images for Lesperance's Amazon project.

Lesperance's present show at the ICA Miami, Amazonknights (30 November 2021–27 March 2022), extends the artist's ongoing research into archives of protest and borrows its title from a 2017 painting by the artist, held in the museum's permanent collection.

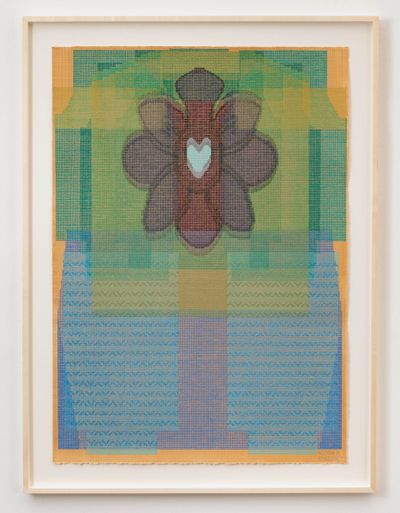

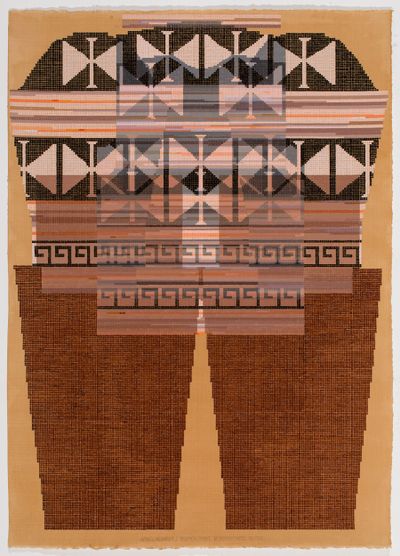

The gouache and graphite on tea-stained paper Amazonknights. Womonspirit. Womonpower. Glory. (2017) depicts a brown piece of knitwear adorned with the labrys symbol, a double-headed axe motif dating back to Ancient Greece, later adopted by the lesbian community in the 1970s to represent strength and self-sufficiency.

Inspired by Bauhaus-era female weavers, body-centric feminist art from the 1970s and 80s, and the Pattern and Decoration movement, Lesperance translates these images into figurative paintings using Symbolcraft, a type of shorthand detailing stiches required to make garments.

The garment paintings, which double as knitting instructions, earned Lesperance the 2010 Betty Bowen Award, which resulted in a corresponding solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum (18 October 2010–3 October 2011).

Likewise, for Lesperance's 2020 solo exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Velvet Fist (26 January–20 September 2020), garment paintings depicting attire worn by protestors at the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp featured besides a participatory project in which viewers were encouraged to borrow a hand-knit sweater ornamented with a battle axe to perform an act of courage.

Recent group shows at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston (26 June–22 October 2019), the Sāo Paulo Museum of Art (23 August–17 November 2019), and the Frye Art Museum in Seattle (21 September 2019–5 January 2020), have positioned Lesperance at the foreground of 'feminist histories' and 'maximalist design'.

Amazonknights at ICA Miami marks the second time the institution has invited an artist to respond to Robert Gober's Untitled (1993–1994), a floor sculpture depicting a punctured nude torso behind a metal grid.

On view is a body of work that departs from historical footage, photographs, and images of protestors' hand-knitted garments, which have been translated into new paintings and sculptures.

Dialling in from her home in Portland, Oregon, Lesperance joined ICA Miami curator Stephanie Seidel on 20 January 2022 to introduce Amazonknights.

Below is an edited transcription of that event, which explores the historical footage and source images that have been translated into new paintings and sculptures that pay homage to feminist activism.

SSEllen, can you talk about how Robert Gober's Untitled in the ICA Miami space became the launch pad for your show?

ELRobert Gober is an important artist to me and has been since my formative years. His work is so meticulously crafted, haunting, and uncanny. It's also multifaceted.

Because Gober was associated with the work of ACT UP in the 1990s, which was related to the AIDS crisis, I started to think about what its presence in the museum in relation to my work might conjure.

In the last 15 years, I have been looking at the work that activists make, the things they wear, and the gestures they perform as they engage in protest. It's called creative direct action. It's the things that they make, the things that they wear, street theatre performances, banner drops, and so on—all to augment the impact of their activism on-site.

For the last ten years, I've been really focused on the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, which was an anti-nuke separatist encampment in England throughout the 1980s and 90s.

For the project, I have been returning to the U.K. to visit archives and speak with activists and photographers that were there to research materials held in their private collections: slides, old photographs, ephemera, and so on.

I was interested in the Greenham Common archives, which are held in museums and public institutions. I wanted to pluck from those archives to create my own archives—to create an archive within the archive of creative direct action, which in this case, was the making of sweaters that bore messages that furthered their argumentative causes. Greenham Common has an incredibly rich history of knitting.

I happened to find out about Gober's floor sculpture when I came across this image of an activist wearing knitwear that formally echoed it.

Unlike the drain you see with the Gober, which is kind of draining a life force out or creating a corpse-like apparition under the floor, this activist's oversized knitted sweater has this heart motif that is embellished with a radiating heart-based centre that looks like petals.

The image reminded me of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, although I'm not a religious person, and I thought that it could be juxtaposed to Gober's floor piece.

Because I had been thinking about the relationship to the Immaculate Heart of Mary and a female subject, as opposed to Gober's incapacitated male subject under the floorboard, it was impossible not to imagine the Gober piece as sort of a patriarchal presence under the floor.

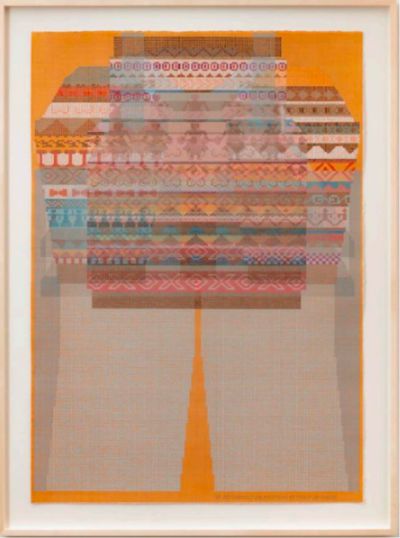

SSWhich brings us to Gloria in Amazonite (2021), the first painting in the gallery.

ELThis painting is made of gouache, which is a water-based paint with dense, rich pigments as opposed to watercolour, which is pretty transparent.

It responds to all the textures in the photo of that activist I just described. Aside from the sweater, she wears a cardigan that hints at texture. She also wears what looks like pants, or maybe pants under a skirt, because you can see at the very bottom this zigzag or rickrack pattern.

So in the painting you have those pant shapes that overlap with the yellow short-sleeved sweater on which I have placed the radiating floral heart emblem at the front and back. The green is the colour of the cardigan that I placed over it. All the layers are represented on a single plane to create an illusion of transparency that shows where the shapes begin and end.

In the show, I frequently use the pattern that I create in the painting as a generative knitting pattern that I knit to recreate the historical sweater that I found and to bring it back into the contemporary era.

The painting Gloria is composed of two garments, just as the image of the protestor had two garments, so it is almost a replication. I also wanted to display it in the same format as the Gober floor piece, so they are of the same dimensions.

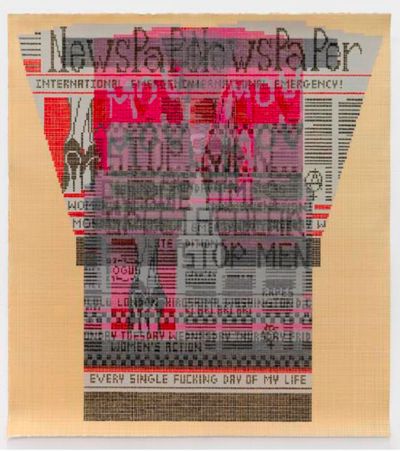

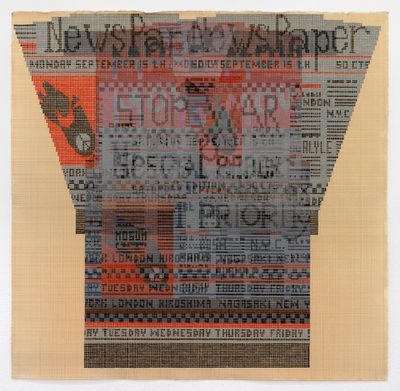

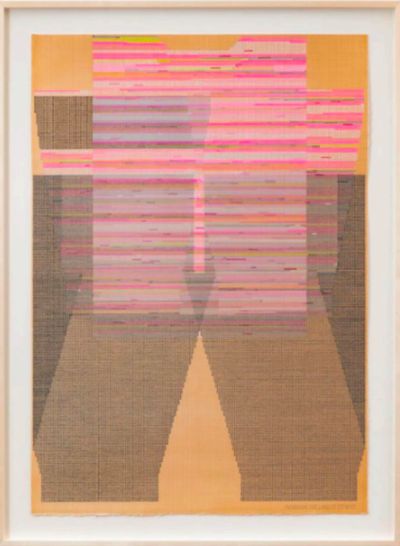

SSTo the right of Gloria, there is a painting with a newspaper image on it. Could you talk about that?

ELStop Men Energie Times Spectacular (2019) is based on another pattern for a Greenham Common sweater that I found. A newspaper motif is at the front and the back of the garment. It also has overlapping sleeves that generate a V shape.

I came across the image of an activist wearing a newspaper-themed garment while researching the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp at the Women's Library, which is a special archive at the London School of Economics. There were a slew of these novelty newspaper sweaters in the 1980s. This one says: 'Stop' on the back and 'Spec'.

I've been looking for a novelty sweater for years with this specific configuration on the back, thinking initially that the garment may have been purchased. Because the source image is in black and white, this opens a few windows for me. There's a way to translate its value structure by imagining what colours comprise the garment, what it said, and what the activist wanted everyone to know when she walked out into the world wearing it.

As I got more cognisant of the history of figuration, I felt self-conscious because it was impossible for me to represent my body or the female subject in this particular medium with its inherent history.

None of the existing novelty sweaters I found were inscribed with 'Stop' or 'Spec' on either side. I believe the activist partially followed the patterning or used one of these novelty sweater patterns as an inspiration for her own re-creation, so I made a series of paintings based on what I imagined 'Stop' and 'Spec' might represent.

In Stop Men Energie Times Spectacular, it gets translated into 'Stop Men' and then the 'Spec' becomes 'Spectacular'. It becomes: 'Stop Men Energie Times Spectacular'.

SSAnd that translation happens again in Stop War 1st Priority (2019)?

EL'Stop War 1st Priority' becomes 'Stop War' and then 'Special', so it becomes 'Special Edition'.

All of them have different titles based on the source image that I found in the archive and on the sweaters themselves. The existing novelty sweaters include language about the days of the week and cities, and they all also feature a single image, so my re-creations include an imagining of what the image might have been.

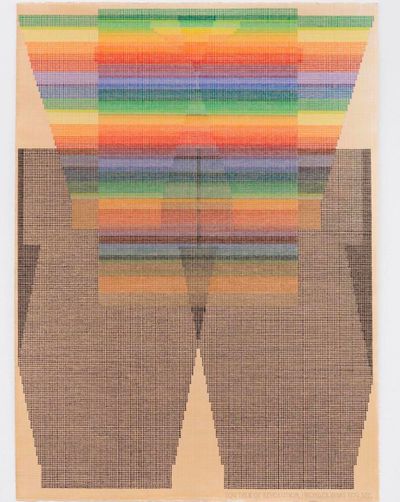

One of my interests in recording the garments from Greenham Common is to track their use of symbols. Take one rainbow sweater painting called You Talk of Revolution, I Wonder What You See, from 2021. This is the source image for that pattern. There is a camper at the site wearing a rainbow sweater shrouded by a cloud of smoke.

This particular picture is from 1983, and it's interesting in the context of Greenham Common to think about the use of the rainbow as this emerging queer symbol and the way that it was utilised by these campers, a lot of them lesbian separatists placed in a dangerous situation.

It was a reclamation of their personal identity and a message to the world about peacemaking and lovemaking.

The rainbow as a symbol was first introduced in 1978, designed by Gilbert Baker. As an emergent symbol, it was quite prominent at the site. This is another image of a camper. She has this rainbow as an armband.

I tracked her for the one hour and four minutes of this particular video and you can see her putting up her tent and helping another woman put up hers. She has an image of a daytime skyscape on the front of her sweater, and then a moon on the back, and she's got this rainbow sleeve.

It's been fascinating to keep going back, looking into this archival material and seeing different iterations of the same messaging, and to see their own homegrown symbol usage be born, expand, and move from one camper to the other, as garments are being shared.

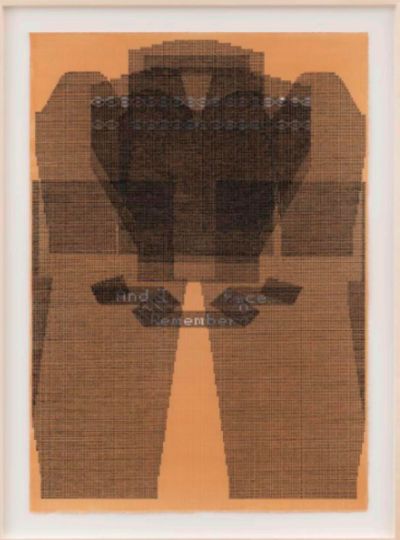

SSCould you talk about And I Will Remember Your Face, a painting from 2020 based on another garment from Greenham Common?

ELAnd I Will Remember Your Face focuses on a black-on-black garment: it's a sweater on top of a sweater, both black, and one has the evil eye, which is a very ancient protective symbol that's popular across cultures.

The black-on-black paintings are difficult and challenging for me. I like the way that they have this austere presence in the space, but making them is challenging because they are just black paint. So to come up with a way to make the black look denser when there's just one value of black relies on a lot of layering and the right brushstrokes.

This particular painting is one of my favourites in the show, although I think it speaks in one of the quietest voices.

SSHow did you arrive at translating these knitted garments into flat pattern paintings?

ELI studied figurative oil painting as a student, and as I got more cognisant of the history of figuration, I felt self-conscious because it was impossible for me to represent my body or the female subject in this particular medium with its inherent history. So I stopped painting for years. I made performative work, I made costumes, I did photography, and I wrote.

The knitting was there, but the painting came too early; it took 20 years for the two to merge.

The creative direct action utilisation of sweaters offered a new way to represent a body that is divorced from that history and that was based on American Symbolcraft, which is the language of knit patterning.

If you look at the back of a knit-pattern book, what I do is just a couple steps removed from the instructional templates. So the knitting was there, but the painting came too early; it took 20 years for the two to merge.

SSI remember you talking about incorporating these archives and protests to give them another life; to transform them into another form of archiving.

When your work is acquired by museums and enters collections, the history of Greenham Common comes with it. That adds to what we see in the gallery, whether these two paintings on the far wall, the piece on the right, which is owned by ICA Miami, or the sweaters in the vitrines that are new pieces created for the show.

ELThis is Amazonknights. Womonspirit. Womonpower. Glory. It features the labrys symbol, which was prominent at Greenham Common. The labrys or the double-sided axe is one of the oldest symbols in Greek civilisation. It was thought to be the weapon of choice of Amazon warrior women, and it was also affiliated with Minoan culture, which was matriarchal.

The symbol was important for strains of feminism in the 1980s, and was knit into a fair amount of garments. It was also a really popular lesbian and feminist strength symbol from the late 1970s to the 90s, and I still see a lot of the labrys today.

It's also important to point out the use of language. The title Amazonknights. Womonspirit. Womonpower. Glory. spells out 'women spirit' as 'W-O-M-O-N', instead of the 'woe of man'.

It's a strange thing to make a painting that also reflects knitting. It's taking two historically unrelated languages and trying to represent a body in a new way and figuring out a language for the yarn is part of that.

There was so much inventive language use and reinvention of the way we think of words at the camp. You can see it in their songbooks and the ephemera that came from the camps. There's a lot of cartoons about it, and some of the things that I came across when I looked for images of the sweaters include these cartoons, as well as letters people wrote to each other, diaries, and calendars.

In a way, all these objects are really precious to me, and they get utilised sometimes in the titles. Many titles, like the previous one, are from songs, or ephemera like this. So these are more inventive spellings of 'women' that are counter-patriarchal.

SSYour book, Velvet Fist (2020), has this fantastic glossary for the different symbols you reference, and you talk a lot about the labrys.

ELThis is the source image for the piece that's owned by the ICA. She's wearing this labrys sweater, which also has a Greek key on it, which is an ancient symbol of a meander, which symbolises life, because it visually represents a long, continuous line that folds back upon itself with complexity.

Then she's also wearing a sweater that appears to be made out of variegated yarn. So that is a fascinating thing for me, when I'm painting, to try to figure out a way to translate a variegated image into paint.

Because it's on a yarn skein, I have to come up with a system to make it work in a painting, so that it keeps the strain of change from the light to the dark values.

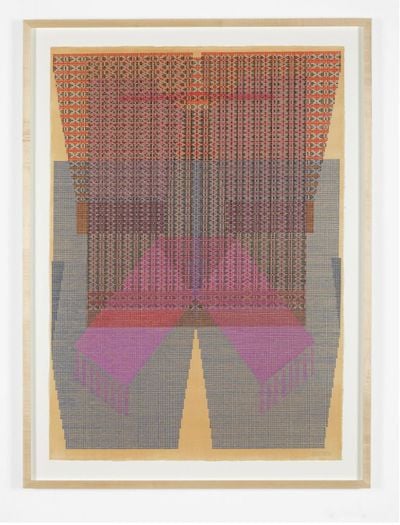

The painting has variegation in it as well, and we'll come to Mourning the Land of Feminye (2021), which has a lot of variegation, and I can explain how that's done. You can see the variegation in this.

It's a strange thing to make a painting that also reflects knitting. It's taking two historically unrelated languages and trying to represent a body in a new way and figuring out a language for the yarn is part of that.

I think that's why I love the variegated paintings so much. Many of the variegated paintings begin with a sample of yarn. I find a yarn that I think would make a variegation, like the one in the source image, and I knit it into a mathematical equation. It's like 120 light pink, 7 white, 40 dark orange, and so on, and then that becomes my rule code, and that rule code follows throughout the painting.

These feats of colour maths, where I'm counting out stitch-by-stitch and each tiny little square is its own equation of colour combinations, achieve this illusion of transparency so that anyone who wants to knit the pattern now or in the future could look and see where the shaping happens in a garment.

It gets really complicated because these garment paintings have a front and a back, two sleeves, and sometimes pants and a garment on top of that.

SSWhat I find so interesting about your incredibly meticulous research into these archives is the point where interpretation sets in, where you continue the archives with your imagination.

ELI used to be stricter about the rules. All artists have rules of engagement with their work, and I have allowed myself to extrapolate more recently, and there's pleasure in feeling like I've familiarised myself with the language enough to do that.

Before I met Nic, an ex-Greenham camper, at a separatist commune in New Mexico in 2005, I had never heard of the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp.

Getting a book like Greenham Women Everywhere (1983) by Alice Cook and Gwyn Kirk, familiarising myself with the movement, and seeing this book's reproduced image of two women leaving prison, one in a sweater with a labrys Fair Isle motif, was an epiphany to me, as they were using symbols like this labrys in inventive and new ways.

I've been knitting since I was a child, and I used to work for Vogue Knitting Magazine in the late 1990s. I had never seen the symbol used as a Fair Isle swatch, so it opened my eyes. It's an important image to me, because it began my process of trying to pull the images out from history and save them.

There are so many interesting things that happened at the Greenham Common camp in terms of symbol usage in the crafting of self-identification.

The image below is another example of a labrys motif sweater: a person standing outside the main gate of the encampment. On the other side of the gate is where all the nuclear cruise missiles are destined to be stored. You can tell it's a hand-knit garment because it's not symmetrical. I also love how dirty it is. She's clearly been living outside, fighting for peace.

This is a gorgeous sweater that I found right before Covid started. I was able to go to England one last time for research, and I met with this woman named Janine Wiedel, who was a photographer at Greenham. She had this stack of contact sheets that nobody had touched for 30 years and she let me come over to her house, sit on her kitchen table, and look through them. There were so many pieces of knitwear inside.

There's a lot of information that you can get from an archival image, even if it's just a partial image. You can see what kind of gauge the yarn is. You can see how thick or thin it is, and that relates to the size of the grid that I make.

In my experience doing this research, I see this knitwear as a creative piece of this movement that has been overlooked.

There's a book that just came out last November about the banners that were made at Greenham Common, and it's great that this particular aspect of their creative making is being investigated. I'm hoping that the fact that there were so many unrecognised women artists at the camp will start to change.

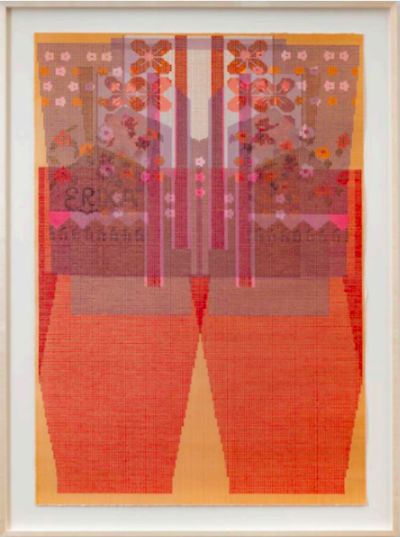

I have this painting in the show called Erika XO (2021), and it's based on a source image that has partial language visible on its sleeve that could be 'Erika' and 'XO'. I wanted to have a painting with another name besides Gloria, and again it is the same scale and dimensions as the Gober grate in the floor.

It's clear that there's this plait or cable that goes through the front of the jacket, and I created it as an XO cable, so it has this voice of love and care as an 'XOXO' that is also instilled into the knitting. There are also all these flowers, which were used and symbolised in knitwear at the camp.

SSWhat is the correlation between the sweaters from the photos and your interpretation of them in your art?

ELThere's a lot of information that you can get from an archival image, even if it's just a partial image. You can see what kind of gauge the yarn is. You can see how thick or thin it is, and that relates to the size of the grid that I make.

You can see the shaping of it—is it a set-in sleeve? An oversized sleeve? A raglan sleeve? Is it a V-neck? All of these things create the shapes of the painting, which is transcribed from the source.

So the shapes come first. Then they get filled and the chromes are either there or they're translated from black and white. Then a lot of information gets filled in based on the images, and then some of the information gets filled in that's ultimately not there.

SSYou've also included a photograph that was in the Greenham Common archive at the People's History Museum in Manchester, right?

ELThere is such a wide-ranging presentation of symbology in that photo, which was taken at the Annual CND Conference in 1988, CND being the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, founded in the 1950s. There's the dove and knit-in texts, a barbed-wire fence, a cruise missile, flowers, and there's a peace flower on the person on the right.

I wanted to reiterate this floral use, and the beauty of nature that presents the very antithesis of something like a nuclear holocaust.

On the other side, there was a very grim military presence with the land completely stripped away to lay the concrete for the largest runway in Europe. In all of these bunkers, there was nature on one side and there was this terrible military civilisation on the other.

An important thing to say about my practice is that while I find these sweaters in archives or photographs from films or videos, often they're partial and I don't see what's going on in the entire garment, or what the entire message is until I do additional research.

Sometimes I find more images of fronts, backs, sleeves, or maybe coloured versions of originally black-and-white images. This painting is a good example. Doves in the Crosshairs (2021) includes the pants, the front, the back, the sleeves, and a scarf.

In terms of this motif of crosshairs on a rifle, and doves on the sleeve; for the longest time, this was the only image that I had of this garment. I couldn't tell those were crosshairs. It looked abstract and potentially metaphysical. There were things growing from the centre, maybe orbs or rays, but there seemed to be something potentially communicative there.

I kept the image close, and then when I was at Janine Wiedel's kitchen table in 2019, I came across another image that shows the same sweater, but you can see more details. With this, I was able to make that painting.

SSCould you talk about the recurring symbol of the dove at Greenham Common?

ELDoves had this real prominence at Greenham Common as a knitwear symbol. Doves have always had symbolic meaning, like in biblical use, where doves are messengers of peace or love. In 1949, at The World Congress of Partisans for Peace in Paris, Picasso was commissioned to design an image that represented peace, and he created a dove drawing.

I think the peace movement and the campaigning for nuclear disarmament of the CND in particular took off with that symbolism, as well as the invention of the peace symbol that we now see everywhere.

At Greenham, doves also appeared on giant banners, so this communicative language goes from one medium to another, and then onto bodies.

There was so much creative making at Greenham Common that transcended into so many mediums, including songwriting and singing. If you look up Greenham Common footage on YouTube, you'll see that they're often engaged in song, and the songs are written by them, or they rewrote the songs of others, or instilled their voices in more traditional pieces.

The representation of their own subjectivity as these protesting female bodies is very present. The title of the last painting in the show, We Are Changers And Everything We Touch Can Change (2021), is a lyric from a Greenham song.

SSDo you also engage with more contemporary examples of protest?

ELI do. I think the era of knitting being a craft that a fair amount of people know and engage in is sort of over, and mass-produced textiles have entered the picture. It's harder than you can imagine, to find an argumentative textile that's worn in a contemporary setting.

I will see one every once in a while, but it's not easy. Protestors are using other things. They're doing other things. It's not about knitwear anymore. More than anything, creative direct action and the visual making of various movements is fascinating to research.

It's based on the particular skills of a group and the materials they had access to, but it's also very inspired and has everything to do with aesthetics and messaging. —[O]