Frog King Kwok

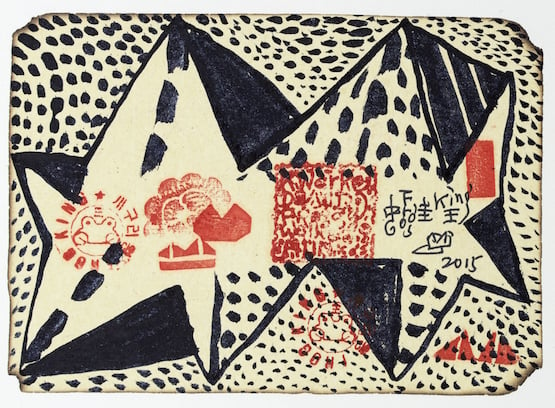

Frog King Kwok. Image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong.

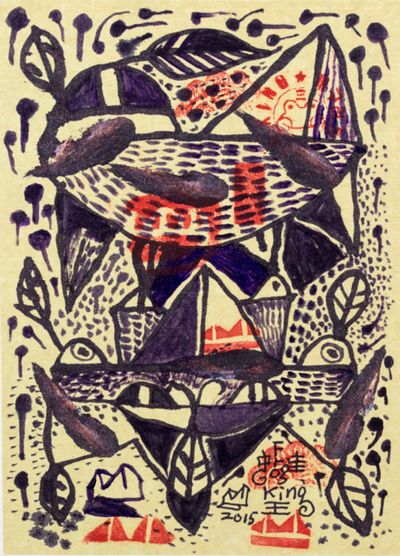

Frog King Kwok. Image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong.

Frog King Kwok (aka Frog King) is one of Hong Kong's earliest conceptual artists, and has been a pioneering influence on the art world ecology within the city since the 1970s.

Beginning his career studying traditional artistic practices, Frog King has since transformed his style, incorporating ink painting with performance and installation. His time living in New York during the 1980s had a particularly strong impact; immersing himself in the live art movement, Frog King coined the phrase hark bun lum (the Cantonese term for 'happenings'). In 2011, Frog King represented Hong Kong at the 54th Venice Biennale with his exhibition Frogtopia・Hongkornucopia, and has since gained increasing recognition for his eccentric practice. Today, Frog King is unmistakable, choosing to dress in his 'froggy' outfit at exhibition openings and performances—a living embodiment of his art.

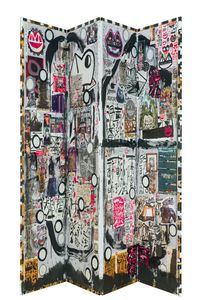

This month, Frog King is participating in Mobile M+ : Live Art, putting together an exhibition which reinterprets his seminal performance works from mid-to-late 1970s, such as his plastic bag project Kwok in Beijing (1979), in a site-specific installation at Connecting Space, North Point. Mobile M+: Live Art positions Frog King's early performance works alongside the likes of John Cage, whom he sites as a key influence after meeting him in New York, and young Hong Kong performance artist Pak Sheung Chuen, accentuating Frog King's pivotal role in the growth of the city's performance art culture. Simultaneously, the artist is also enjoying a solo exhibition at 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, showing a selection of his most recent ink paintings and an installation work at its space in central Hong Kong.

Frog King found the time to speak with Ocula Magazine about his artistic ethos, influences, latest exhibitions, and his continually developing practice.

You've been creating works of art since 1967, and have participated in over 3,000 art events. How would describe your artistic approach?

In the seventies, I based my work on the conceptual. Before I do a visual work, I draw the idea. In my mind, in my head, it is spinning very fast. I'm a Pisces; Pisces have many ideas and are very artistic. Conceptual art is about what's inside the mind. And when you're doing something, it has no meaning or regulations. So inside I am innocent and naive.

What led you to create the art you make?

Initially, I joined a community of people, and a lot of them were creating their own shows. When I went to openings in the seventies—with people holding champagne or wine, standing there, dressed up nicely, that kind of party—I felt uncomfortable. So, many times, I went and made trouble. Sometimes I threw things around and also complained—many times people kicked me out. But actually, I was the one who wanted to balance the community. To raise the question of 'what is art?'

In the eighties, I felt that New York was the capital of art in the world, so I went to New York, coming back to Hong Kong around 20 years later.

You were trained in traditional calligraphy, ink painting, Chinese poetry, and philosophy, but today your work is very different. How do you feel your traditional grounding influences or impacts on the work that you produce today?

I got used to the medium, and now I apply it to any of the events I participate in or create. It works well; it is my mother tongue and part of my heritage. So I show up on the stage, with different formats and different faces for the community. Everybody wants different and special things, so that works out well.

So the traditional is your grounding point, your mother tongue?

Yes, my mother tongue. But say you go to an opening; no matter how fashionable you are you're still a regular. You can wear your jewellery or your branded clothing, and you're still a regular. There are too many of those things. You have to be different, and you have to be individual. You have to have the spirit that stands out in the community.

Do you plan to add more works to the show?

It depends. Sometimes I empty my brain before walking into the gallery and begin working by chance. John Cage used chance to make his work, and I also use this direction, fitting together many chances. It's like a madness; each chance is a ping-pong, it's a beat, which together turns into one unifying system. You can still play, but the mind is very serious. You have to have the philosophy to discipline yourself.

You mention John Cage and your time in New York. How do you feel that time and the artists that you met there have influenced your practice?

John Cage is the godfather of new music in the history of the world. So he is very interesting; we can look at him as a role model.

I do my best to create multimedia works, looking at the master's keys. I had the chance to connect with John Cage because I met his assistant, Andrew Culver. I also had the chance to invite John Cage to see my show in the early nineties in New York, and I gave John Cage some calligraphy.

You say your 'froggy' sunglasses act as a bridge between the East and West, equalising people's vision in a way that enables them to perceive of the world differently. Would you say this is the underlying concept in your work?

When I met Mayor Dinkins in New York, I gave him the 'froggy' sunglasses to wear, and he said 'I trust you.' I felt very moved, so I started this project, Equality.

The president, a pig, and regular people have all worn the sunglasses and after they are equal. So I have developed 'frogtopia'—ideal happiness in the new world. People can experience one second of happiness with the 'froggy' sunglasses; it is a life-body installation. I've turned Andy Warhol's 15 minutes into one second.

Nowadays, fighting and violence are everywhere. Artists keep a balance; they keep harmony and some happiness. We cannot do much. We do a little at a time and keep life going. Art is about continuing to 'froggy'; that's the right direction.

Your work has shifted from performances on the street and in public spaces, such as your plastic bag project Kwok in Beijing (1979) that took place in Tiananmen Square and on the Great Wall, to more recent exhibitions such as Mobile M+ : Live Art, which restages your public performances within a gallery. Why did you initially choose to create art on the street? And do you feel showing your works in the gallery space creates a similar outcome?

In the eighties, there was the energy of youth and graffiti. I didn't worry; I tried anything. But now, I am getting older, and the exploration period has calmed down. I've been through many generations and experience. So, now is the time to harvest the golden age. Now I feel as though condensed energy can make a work.

In the back room at 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, you are showing your smaller ink works, which you paint late at night. Do you feel these encapsulate this more mature style you are referring to?

Those works are like a healing medicine, because in the daytime, there is a lot of stress. You have to be on time in some location, you have to report, react to emails, or those many messages. And you cannot be late. So at night, I try to empty my brain and then do those drawings, which are like a meditation. I didn't know what was coming out; they automatically came out of the process. They are extraordinary spiritual works.

Your studio is based in the Cattle Depot Artist Village, which is now becoming a focal point for Hong Kong's artist community. Could you share your thoughts on the developing position of artists in the art world ecology of Hong Kong?

In Hong Kong, to be a professional artist is a very rare business. There are very few examples of professional full-time artists surviving in Hong Kong. A while ago, it was a cultural desert. Now with further evolution, it has become more established. There's the Art Council in Hong Kong, and they give us funding, and some commercial organisations sometimes support artists, often because of tax. So more frequently, younger people and arts groups have sponsors.

But I don't apply for funding; I try to find freelance jobs to fund my time. So in Cattle Depot Artist Village, my project is the Frog King Kwok Museum. When I stay there, I take care of visitors. But when I'm busy or out of town, I lock the door; nobody complains, because I haven't applied for funding, I'm not a servant working for the government. I brought the East Village spirit to Hong Kong; first in Oil Street and now Cattle Depot. Most of my friends have moved out, but I stay. It's very hard to survive, because I'm not working. I have to find ways to pay the rent, art projects, and expenses.

In 2011, I suddenly got the chance to go to the Venice Biennale, and now it looks like I've got a certificate to be an artist. So it's giving the new generation an example, that life as an artist is a realistic thing if you insist on it.

While you amalgamate multiple mediums in your practice, you continue to remain faithful to ink. What draws you to this artistic practice in particular?

Nowadays, the digital generation is missing out on the human touch and physical approach. The computer cannot do calligraphy, so I have a position, which connects the past and the future. It is hard to do, but I found ink is spiritual and creative—a free medium. I can apply this to all different media, including painting, performance, or the digital. I'm working on a public art installation, which is in the Ho Man Tin station. One work is called Frogtopia Arch, it's a huge sculpture. Another one is Frogscape, which is a stainless steel work that it is between a painting and sculpture.

One final question—since your exhibition, Totem, at 10 Chancery Lane Gallery last year, how do you feel your practice has developed? What do you think is different about this exhibition compared to last year's exhibition?

We cannot repeat art, but we can relate it and make a contrast, as we are serving the community. For this show, I have another new performance, Time Frog, which is related to 100 clocks. I will interact with people, and as a 'frog king kung fu master', will paint hundreds of clocks. The work will be related to chance and time, as the clock is the symbol of time. —[O]