GaHee Park: Building Fluid Worlds

GaHee Park. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

GaHee Park. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

GaHee Park's still life paintings and drawings portray intimate scenes from everyday life. Subjects, either solo or in embrace, are depicted in private and often erotic settings accompanied by animals and plants, all engaged with dismantling the separation between public and private space.

Born in Seoul in 1985, Park was raised in a strict conservative Catholic family. As she explains, sex and sexuality were no-go areas for discussion or exploration growing up, both in her household and wider society. Her arrival to the U.S. in the late 2000s for graduate studies at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia led to new-found liberation and room for interrogating, rethinking, and disrupting preconceived attitudes towards the female body, gender roles, pleasure, and eroticism in her painting-led practice.

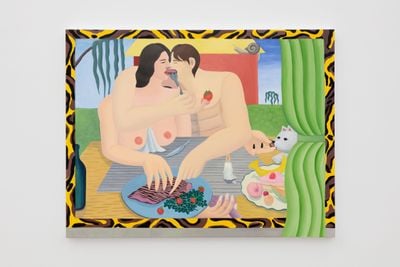

Standing in front of Park's beguiling work, We Used to Be Fish (2019), the viewer encounters a nude heterosexual couple, the woman dressed in thigh-high boots with black manicured nails, having a relaxing evening in a what looks like a giant aquarium. Sipping on cocktails and smoking, a variety of sea creatures share the space with them, while a cat watches curiously from the outside. The flatness of forms and colourful explosion of flora and fauna collapse the barriers between interior and exterior to present a space of peaceful co-existence, where there are no hierarchical separations between beings.

Conversely, as suggested in its title, Invitation (2020) encourages the viewer to look closer within, as a raven-haired female protagonist draws back a purple curtain to reveal her companion's nude torso reflected in the mirror within the frame. Sex—or at least an implication of it—features prominently in Park's paintings and drawings that are all framed within surreal spaces that blur the boundaries between public and private space to set up a voyeuristic perspective.

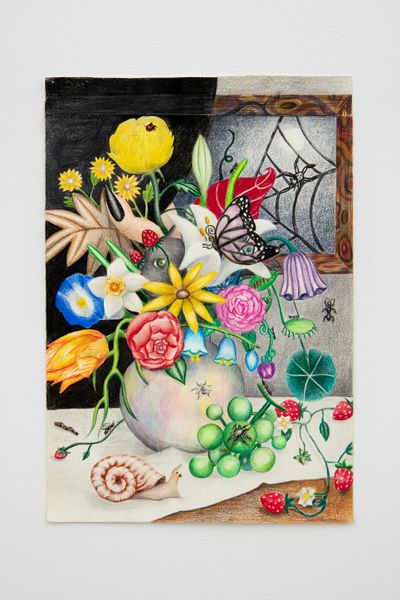

Betrayal (Sweet Blood), Park's expansive solo exhibition of new paintings and drawings will take over two floors of Perrotin New York between 12 September and 17 October 2020. This new body of work sees Park introduce herself as the subject for the first time to further explore the body's absence and presence through frames within frames, mirrors, multiple gazes, and shadows. Additionally, her painting, Still life with Living Things (2020) is one of 50 artworks in Art on the Grid (29 June–20 September 2020), a group exhibition commissioned by Public Art Fund on the city's public transportation and communication infrastructure including 500 bus shelters' advertising panels and on more than 1,700 WiFi kiosks' digital screens across five New York City boroughs.

Park speaks to Ocula about the playful and provocative approach to sex in her paintings, which deal with intimacy, eroticism, and femininity.

JDYour move to the U.S. represented a physical and mental breakaway from a conservative Catholic upbringing. How did this move shape your practice?

GPI felt mentally oppressed living with religious parents and in a conservative, patriarchal culture offered in a country like Korea. I had no choices growing up. I had to go to church every Sunday, I played the organ at 6 am every day, and attended bible readings frequently. But at the same time, in my textbook and notes, I was drawing some sexual images, what one would deem as forbidden stuff. It was a way of rebelling and asserting myself, I guess.

Finishing a painting can take a few months, so drawing helps me keep ideas alive, like I am building an organic and fluid world.

I was always drawn to making art and knew this was something that I wanted to pursue. When I was in art school in Korea in my twenties, people kept going on and on about how hard it was to be an artist as a woman. I began to realise that there were far fewer female artists and professors than male ones. At the time in Korea, it didn't seem like an art career was a possibility for me, which meant that I originally studied English before transferring to the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia where I met very encouraging teachers and peers. That's when I felt like I could be free to pursue what I wanted. Being mentally and physically far away from Korea helped me think clearly about what kind of life and art practice I wanted to have as an adult.

JDDrawing is important to you. Is this something you see as separate or as part of your paintings?

GPI make one image over and over to understand the space, or depth of field, in the work. I draw first then make another drawing of a similar image that I then eventually use as the basis for my paintings. But even while I paint, I go back and draw the same image in different versions. Since drawing is faster, smaller, and more immediate, it feels rawer and more unexpected. Finishing a painting can take a few months, so drawing helps me keep ideas alive, like I am building an organic and fluid world. Very often, this practice leads to the next painting and then becomes a body of work. Sometimes, when the scale changes from drawing to painting, the painting no longer looks interesting to me, so I then have to improvise.

JDHow important has it been for you to continue this reclaiming the gaze of the female nude, which art history traditionally rendered to that of the male artist and his gaze?

GPIn Korea, I always loved going to public baths. Whenever I return, I visit different Korean baths with my friends or with my mother. It is a very open and relaxed environment where women of all ages converse, take baths, scrub their bodies, and soak in hot or cold water. It's like this liberating zone where, unlike in everyday life in Korea, women can be nude without being sexualised by the presence and gaze of men.

I am interested in how domestic spaces are a reflection of our society.

From a young age, I've always loved looking at and learning about nudes and female bodies. But at some point, I felt very uncomfortable looking at them, especially in the context of art and art history. I wanted to make nudes and represent bodies from my perspective, and I think this is important for me and my practice. It is still not always comfortable for me to make female nudes, and I fight the shame I learned from my upbringing, but it's also not about creating a pornographic image. I want to describe something intimate and personal in my images.

JDCould you expand on your interest in the domestic space and capturing intimacy through these abstracted and surreal worlds in your paintings and drawings?

GPI am interested in how domestic spaces are a reflection of our society. I grew up in a patriarchal household where I barely had privacy. I channelled my need to express myself and have some mental freedom in the margins of my notebooks. I drew or ranted a lot in my notebooks, then I would hide these parts by gluing them so no one could see. I feel like these notebook areas have expanded to the canvas and to the studio. But also, to my home life, figuring out how to feel free in my personal life as well as my art practice.

JDPaintings such as Early Supper (2019) and Willow Tree (2019), presented in your solo exhibition, We Used to Be Fish at Perrotin Seoul in 2019, bring together intimate portraits of individuals with plants and animals. Is this coming together of bodies and nature a way to dispel taboos around sex?

GPI'm curious about the perspectives of animals and other living things, and how they interact with our lives and we interact with theirs. I started to think about animals' perspectives more when I moved to America. As an Asian woman whose first language wasn't English, people looked at me and treated me differently. I felt discriminated against, and it made me mad. That feeling was painful, but there was also something about it that intrigued me.

In a single image, I'm trying to express the multiple ways we inhabit our bodies: physically, psychologically, sexually, socially, and so on.

Being discounted as a person, almost feeling invisible, I started to imagine I was like a cat or dog at the side of the room, just watching, observing people who were acting like I couldn't see or understand them. It gave me a new perspective, which I've explored with the animals in my work. So I don't know if I think about it as being explicitly about sexual taboos, maybe it's more about social taboos, about power dynamics and hierarchies—the values we give to certain people and life forms over others. But also there's an intimacy we can have with animals, which is kind of primal and deep as well.

JDMirrors, frames, and windows feature a lot in your works. Do they represent portals to new ways of thinking and engaging with bodies?

GPI often use mirrors, frames, windows, or fragmented bodies because I want to add subplots or little narrative fragments inside my paintings, which complement the central image. I enjoy the techniques for doing this in films and literature, like split screenshots in films, or flashbacks, dream sequences, or parallel stories in a novel. I try to do something like that in my work, to expand the physical, psychological, and temporal spaces. And also to emphasise and complicate the perspectives. Who is seeing what? Is what they are seeing real?

JDFragmented body parts appear somewhat contorted and fluid. Are they indicative of fluidity of sexualities and prescribed gender roles?

GPThe contorted, fluid, and fragmented body parts in my work come from this approach too. We experience everything through our bodies, which are always changing and transforming over time. In a single image, I'm trying to express the multiple ways we inhabit our bodies: physically, psychologically, sexually, socially, and so on.

JDFor Betrayal (Sweet Blood), your latest exhibition at Perrotin New York, you draw on themes from Charlie Chaplin's 1921 silent movie, The Idle Class, centred on dual personalities. Can you expand on this inspiration?

GPThe title of the new show comes from the title of one of the paintings, Betrayal (Sweet Blood). I built the image in that work after a famous scene in Charlie Chaplin's film The Idle Class. Chaplin gets a note from his wife saying she won't see him until he stops drinking. He turns his back to the camera and starts shaking like he's crying, but when he turns around, we see that he's actually just shaking a cocktail. After watching the film, I used this gesture to tease my husband a lot.

I liked how the comedy came from the ambiguity between the gesture and its expected emotion. I turned this into an image of a woman who seems to be crying and laughing and watching at the same time—she's making a gesture for one emotion while hiding other different emotions.

I am always looking for what is strange in 'normal' life and trying to express that in my work, both through the subject of the works and the way they are painted or drawn, using different colours, textures, and disorienting perspectives.

I thought about calling the show Betrayal because it seemed like a good title to suggest a dramatic situation. But then my husband mentioned this phrase, 'betraying emotion'. I started thinking about how that expression suggests that showing emotion is a kind of betrayal. It seemed like a very male perspective to me; like showing emotion was breaking the rules. But it was also kind of exciting, like an inner rebellion. This idea seemed to fit well with that image and many of the other works in the show.

Additionally, Sweet Blood references the mosquito on her hand, by introducing the perspective of the insect. I wanted to consider a range of emotions, not as a betrayal of the rules of proper behaviour, but as an essential part to life.

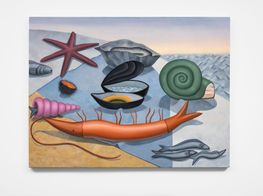

JDI see the uncanny defined by Freud as 'the familiar made strange' operating in your most recent paintings, such as Seafood Dream and Voyeur. Do you seek to remove the viewer out of their comfort zone?

GPYes, I agree. I remove the viewer from their comfort zone but also myself as well. I am always looking for what is strange in 'normal' life and trying to express that in my work, both through the subject of the works and the way they are painted or drawn, using different colours, textures, and disorienting perspectives.

JDAs well as your solo exhibition at Perrotin, your work, Still Life with Living Things (2020) is showing in New York as part of Public Art Fund's Art on the Grid city-wide project reflecting on 'COVID-19 and the renewed urgency over systemic racism'.

This format of public art is particularly poignant given the pandemic and much of life now safely happening outside. How have you engaged with working on this site-specific public art project?

GPSince I started working at home because of the pandemic, I've been spending more time outside—eating in parks, walking around my neighbourhood—which a lot of people have been doing as well. This has meant I've been paying more attention to the intricate details of the parks, yards, and people's gardens; imagining a whole little universe that exists in one little corner of someone's front garden. In a sense, Still Life with Living Things is a manifestation of an expansion in what I think of as 'my community' to now include plants, animals, and insects in my neighbourhood, so it seemed like a good subject for a public-facing artwork.

JDHow have these two major events—the pandemic and the ongoing racial uprising—allowed you to reflect on your experience as a Korean living in New York, given the rise in prejudices against Asians during the pandemic particularly?

GPI'm definitely paying close attention to recent events and the conversations around them. I'm glad that these issues are being taken more seriously now. But the surge in racist attacks is also scary of course. I feel like a lot of these issues—the power dynamics in our society, systemic racism, cultural roles, and stereotypes—are things I'm always thinking about, and they've always been part of my work, even if it's sometimes in abstract or indirect ways. But there's a lot happening right now, so it's hard to say how it's affecting my practice. We'll see!—[O]