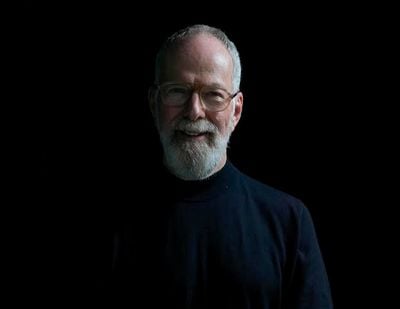

John Kaldor

Image: John Kaldor AO. Image courtesy of Kaldor Public Art Projects.

Image: John Kaldor AO. Image courtesy of Kaldor Public Art Projects.

Since 1969, arts patron and collector John Kaldor has been sharing his love of contemporary art with the Australian public through what is now his non-profit organisation Kaldor Public Art Projects, which commissions major large-scale projects from well-known international artists.

Kaldor has participated on the boards and international councils of many art organisations over the years, and is currently on the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was also commissioner for the Australian Pavilion at the 51st and 52nd Venice Biennales.

In 2011, Kaldor gifted his private collection which included works by Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Long, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Sol LeWitt, Jeff Koons, Ugo Rondinone, and Bill Viola to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, bringing the works into public view. The 32nd Kaldor Public Art Project presents Australian-Aboriginal artist Jonathan Jones' barrangal dyara (skin and bones), which is on view in the Sydney Royal Botanic Garden from 17 September–3 October 2016.

SAPlease tell us about your introduction to contemporary art in the early 1960s. How did you discover it? What excited you about contemporary art then?

JKI was trained as a textile designer, and in my job I was required to travel regularly to the US and Europe to see the latest fashion trends. During that time, Pop art emerged as a very strong movement, primarily in New York. Coming from Australia, what I saw was totally new and it really excited me. It was so different from the landscape-based works that were prominent here. It was the first radical movement after the post-war years, and it was the beginning of consumer society, of affluence, which Pop art both reflected and commented on.

SAWhat inspired you to initiate Kaldor Public Art Projects in 1969?

JKOn these initial trips to the US and Europe—as a junior employee on a low salary—I started collecting small works by artists like Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, which at that time were cheaper than works by Australian artists such as John Olsen or Fred Williams. I could buy a small work by Andy Warhol for as little as USD 50 or USD 60.

Contemporary art at that time was a very small club. Only a few people were collecting and it was shown in only a handful of galleries. It was so different to the recent explosion in the field, where there is now an enormous market with many galleries, artists and collectors.

After a while, I began to feel that collecting was a very selfish thing because you see it, your family sees it, friends see it, but the general public doesn't, and I wanted to share my love of art with the art community and the general public. That's why I wanted to bring international artists to Australia.

SAAt the time, Australian audiences wouldn't have seen a lot of international contemporary art. Was there a real hunger to see such art?

JKYes, Australian audiences didn't have access to it. It just didn't come to Australia. The only way they saw such art was through reproductions, which was a terribly second-hand way of seeing it.

It was a shock to see contemporary art. It was a shock to me when I first travelled. I just wanted to expose people to it. I was hoping that the reaction would be positive, but that wasn't my priority. If people didn't like it immediately, maybe in a few years they would think 'oh, that was interesting', or 'that makes sense to me now'.

SASo the main focus of the Kaldor Public Art Projects is education?

JKFrom the very beginning, the aim was for people to see groundbreaking art. The mere act of presenting this art was intrinsically educational in a very non-didactic way; we [Kaldor Public Art Projects] didn't have a formal education program until 2011.

Since we presented Christo and Jeanne-Claude's Wrapped Coast in 1969, our art projects have always been free. Thereby providing equal access for the public, without hierarchy, and we hoped that this would encourage audiences to come to our projects, particularly those who might not ordinarily go to the traditional white-cube gallery space.

SAThe work you present is quite avant-garde. It is often performance or installation based. How do you choose the art for your projects?

JKWell, what we are trying to do is always exhibit the latest developments in contemporary art. It really depends on what I feel is the art of the moment. It should be something that has meaning and relevance to what is going on today. If 10 years ago someone had said we would be presenting performance or dance projects—like our 2015 project with French choreographer Xavier Le Roy—I would have said, 'you are out of your mind', because we are about visual art. But in the last few years we have seen a breakdown of boundaries between different art forms. The distinction between visual arts, performance and dance no longer exists in traditional, prescriptive ways.

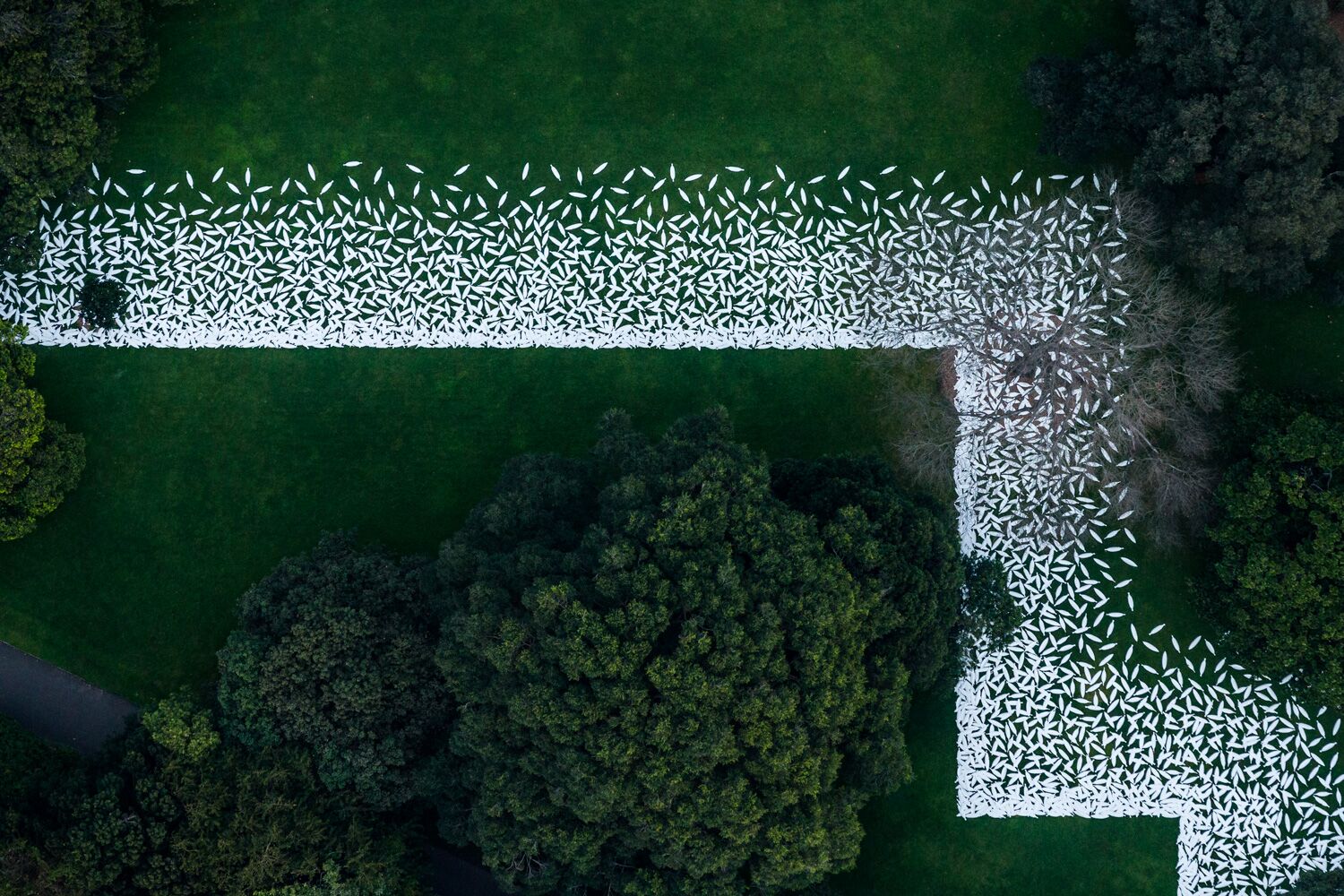

SAFor the 32nd Kaldor Public Art Project, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones is currently presenting barrangal dyara (skin and bones) in the Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney. This is the first time an Australian Indigenous artist has been chosen for a Kaldor project. Please tell us why Jones was chosen, and about the particular work he is presenting.

JKFor our 45th anniversary in 2014 we wanted to do something different, so instead of inviting an international artist we held a competition open to Australian and Australian-resident artists. The brief was to come up with a concept that could be the foundation for a project. We had 160 entries, and an international jury unanimously chose Jonathan as the winner of the competition. At that time Jonathan had only a concept, so we have been working solidly for over a year to turn that concept into a reality. It's going to be one of our most important projects.

The project recreates the Garden Palace, built for the Sydney International Exhibition, which opened in the Botanic Garden in Sydney in 1879. Sadly, the Garden Palace burnt down in 1882. The exhibition was part of the World Fair phenomena, which began with the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851 and spread across the world. The Sydney showing housed international contributions from countries that included France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and Japan. Indeed, it was the first time Japan had shown overseas.

I collect a particular work because it says something to me. It is never an intellectual exercise; there is always an emotional or a gut reaction, really. If I like a particular artist, I collect their work over the years. I think if you like an artist you have to collect their work over a period of time to really understand their concepts.

The Garden Palace was an enormous building, with a floor area measuring over 112,000 metres. It was nearly three times the size of Sydney's Queen Victoria Building, and stretched almost to the Conservatorium of Music on the north side and to the State Library on the south side of the garden. Yet today it is totally forgotten. If you asked a hundred people, maybe one person will have heard something about it, so we are really looking at re-creating an important part of Sydney's history.

Jonathan is coming from an Indigenous angle, focusing on the part of the [1879] exhibition that featured an ethnographic court display of Aboriginal shields and weapons. The display was included to juxtapose the progress that had been made since white settlement with the 'primitive' nature of Aboriginal culture. It was presented to excuse white settlement and the ongoing devastation of Aboriginal Australia. After the exhibition, which lasted one year, the Garden Palace was used as a cultural centre and as a storage place for the Aboriginal artefacts, which were subsequently destroyed in the fire. So it was a tremendous loss to the Indigenous community. All of their early objects had been lost.

Jonathan is looking to turn this loss into something positive. While the objects have been lost, the culture thrives and lives on.

SAWhat do you think about today's international contemporary art market? Contemporary art has gone from being quite an esoteric, avant-garde field to very much a mainstream attraction, with multiple global art fairs, biennales, and blockbuster exhibitions. What is your feeling about this? Are there negative aspects to this kind of booming market?

JKWell, yes, there are negative aspects because galleries are very market-driven—that's their business. There is a pressure on artists to always come up with something new, and a pressure on young artists to develop very quickly. There is also the danger that, because art is now like fashion, artists are discarded in favour of the new.

SASo what happens when you take that art away from the market, which is what you do with your projects, and you take it into the public sphere, allow people to see it for free, and to learn from it. Does that process somehow change the art?

JKThe art is not commercial; it cannot be sold. The purpose is different. Because it isn't commercial, and the projects are temporary, there's much more freedom in the scope of subjects the artist can work with. There's room to create new concepts, and experiment with innovative ways of communicating with the public.

SAIn 2011, you gifted your private collection to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Please tell us about the works in that gift.

JKThe collection starts with American Pop art and includes Minimal art, German photography, and artists who worked in the 1990s and early 2000s. I am constantly adding to the collection.

I'm drawn to large and difficult works which don't fit into my home, so in the end they find a home at the gallery.

SAAustralia does not have a strong tradition of philanthropy. Do you think this is changing?

JKChanging, yes, but not fast enough. We have to celebrate the achievements of philanthropy, whether it is in the field of medicine, culture, education or art. Also, those who are asking for support—the development managers of philanthropic organisations—have to be more professional. In the US it is a well-regarded profession, and it is an accepted way of running not-for-profit organisations. In Australia there is a cringe factor in asking for support.

SADo you still collect? What drives you to collect a particular artist/work?

JKYes, I am still collecting. I collect a particular work because it says something to me. It is never an intellectual exercise; there is always an emotional or a gut reaction, really. If I like a particular artist, I collect their work over the years. I think if you like an artist you have to collect their work over a period of time to really understand their concepts. —[O]