Judy Chicago Comes Out Swinging

In Collaboration with New Museum, New York

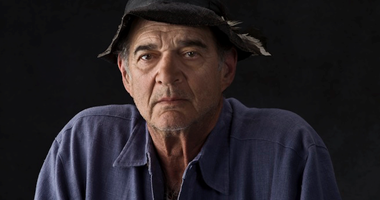

Judy Chicago, 2023. © Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society, New York. Photo: Donald Woodman.

Judy Chicago, 2023. © Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society, New York. Photo: Donald Woodman.

When Judy Chicago asked New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni why he chose to exhibit her work, he responded, 'You are an artist who had to rebuild the house of American art so that you, and many people like you, could live in it.'

This conversation took place on the opening day of the New York museum's survey of Judy Chicago, Herstory (12 October 2023–14 January 2024). The exhibition adopts a curatorial framework to present Chicago's pioneering contributions to feminist art history, positioning her six-decade practice amid the rise of second-wave feminism and highlighting her conviction for preserving women's histories.

The exhibition follows the artist's 2021 retrospective at the de Young museum in San Francisco, which aimed to expand the understanding of Chicago's practice beyond her well-documented magnum opus The Dinner Party (1974–79). The installation features painted ceramic plates with stylised depictions of vulvas in dinner settings that honour historical and mythological women. First shown in 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in California, since 2007 The Dinner Party has been on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

Chicago's practice spans a diverse range of media, including sculpture, painting, installation, drawing, textiles, photography, stained glass, and printmaking. Like the de Young retrospective, the New Museum exhibition lightly touches on some of the better-known parts of Chicago's career to illustrate a fuller breadth of practice, focusing on projects that have largely remained understudied until recent years.

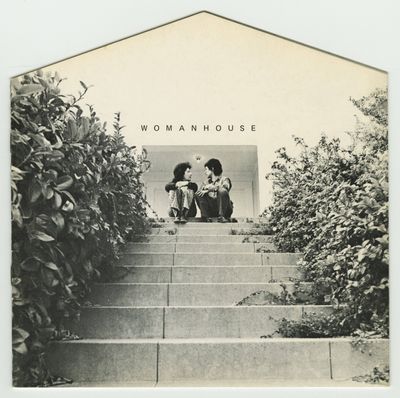

Chicago's works scale four floors of the New Museum, with sections of each floor focusing on a specific subject or material. One such section explores the groundbreaking Womanhouse (1972)—a month-long installation and performance space organised by Chicago with Miriam Schapiro as part of the first feminist art programme at California State University (now California Institute of the Arts) in Fresno.

Herstory begins with the minimalist sculpture Rainbow Pickett (1965/2021)—a reconstruction of the multicoloured geometric work that was included in the 1966 Primary Structures exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York. Chicago was one of three women—alongside Anne Truitt and Tina Matkovic—in a roster of more than 40 male artists, including Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt. 'Even a person like me, who was aware of Primary Structures, did not know you were in that show until I started paying attention to your work,' Gioni told Chicago.

Several critics have noted that Chicago represented the sensibilities of artists working in the West Coast, in contrast to her peers based in New York when the exhibition was staged—a divide the show underscored. However, in Los Angeles, Chicago was also outnumbered; at the time of the New York exhibition, she was one of the few women artists to be represented by Ferus Gallery alongside artists like Robert Irwin and Ed Ruscha.

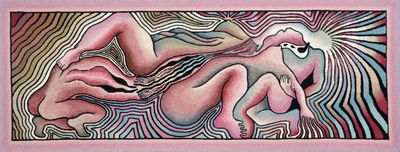

The New Museum exhibition reiterates how radical and incisive Chicago's pieces were at the time of their creation when the art world was often hostile towards or excluded women. While some of Chicago's works are more direct in their message, some of the strongest presentations in the exhibition take a more abstract approach to their activism, like the exuberantly psychedelic paintings from the 'Through the Flower' series of the 1970s, which are displayed together in a dedicated space and evoke the distinct 'dissolving sensation' of the female orgasm, Chicago has said.

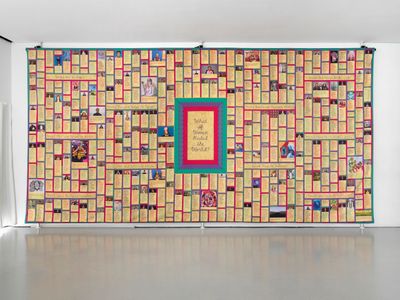

In keeping with Chicago's career-long focus on championing other women's achievements, an installation across the fourth floor of the museum—titled The City of Ladies after the medieval text The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) by Italian-French poet Christine de Pizan—places Chicago's work at the centre of an altar-like space filled with works by nearly 90 women including Artemisia Gentileschi, Elizabeth Catlett, and Hilma af Klint.

Envisaging a women-led world, the works on this floor are ceremoniously flanked by a series of ten tapestries suspended from the ceiling that are emblazoned with feminist maxims like: 'Would God be Female' and 'Would Buildings Resemble Wombs?' It is a version of the architectural installation The Female Divine (2020), which was originally shown at the Musée Rodin Sculpture Garden in Paris in collaboration with Dior.

In this conversation, which is an edited version of the talk that took place between Chicago and Gioni at the New Museum on 12 October 2023, the artist discusses her work, including the importance of research and retrospection in formulating one's own approach to feminism, artmaking, and life. She also shares the story of how she debuted her name.

MGFor you, what is an artist or who is an artist? I think your answer might lead us to understand how you made your work and what expectations you put towards being an artist.

JCI never wanted to be anything but an artist. I started drawing before I started talking, and I started studying art when I was five. My father raised me with the idea that the purpose of life is to make a contribution. I wasn't quite sure what my destiny was except to become part of art history and try to contribute to change.

When I went to the Art Institute of Chicago, I had a teacher who I studied with I think from the time I was 11 until I left at 17. When The Dinner Party went to Chicago, I took him there and walked around with him. He spoke in a very soft voice and said to me, 'I always knew you were going to do something important.'

I didn't exactly know what I was going to do. I didn't know what challenges I was going to encounter. This show [Herstory] and this moment have a lot of resonance, not only for me but for some of the people in the audience who were at The Dinner Party opening in 1980, and our friend, Diane Gelon, who mounted the first grassroots exhibition of The Dinner Party when it was the piece that everybody wanted to see, and nobody wanted to show.

After it opened, it was savaged by Hilton Kramer at the New York Times and Robert Hughes in Time magazine. Kramer was probably one of the most important critics in the country. He described The Dinner Party as 'vaginas on plates', and Hughes wrote, 'If only the needleworkers could have done their own designs,' which betrayed a total lack of understanding of the history of needlework, because historically needle workers work from patterns—they don't do their own designs.

When The Dinner Party compelled people around the world to organise and establish their own organisations and institutions to bring The Dinner Party on a worldwide tour to an audience of a million people, I saw the power of art. I always believed in art, but that was something quite different—to see art inspiring action where people sent cancelled cheques to their local museums, telling them they were not supporting them because they wouldn't bring a piece they wanted to see. That dramatically expanded my idea about what an artist was—to make me feel like art can be such an important part of human life and that artists have an obligation to think beyond the marketplace.

When I started out in L.A. there was no marketplace. People say to me, 'Isn't it horrible you've had to wait so long for recognition?' First, recognition was not my goal. I had a different set of goals, which was to make change and make a contribution. I had five solid decades of working in my studio without ever thinking about the market, which is unthinkable for young artists now. It's only in the last ten years when [my husband] Donald [Woodman] and I realised it's no fun to be in America without any money that we even started thinking about money.

I have followed your career, Massimiliano, since you did The Great Mother show (2015) in Milan, which taught me a big lesson. Donald and I went to Milan to see [it]. It was a revelation to me because you had put together evidence that there had been images of birth from the beginning of the 20th century and in the various movements—Dada, Surrealism. I knew all about the erasure of women's achievements, but what your show taught me was that there are other forms of erasure by the patriarchal paradigm, including the erasure of subject matter that wasn't considered important because it is what women do.

When I was working on The Birth Project (1980–85) in the 1980s I thought there were no images of birth in contemporary art. It was before Frida Kahlo's My Birth (1932) became well-known; a time when Kahlo was referred to as Diego Rivera's wife who also paints.

If anybody visited me in the sixties, I would never even serve them a cup of tea because that would disqualify me as 'just a woman'...

It was because I thought there were no images of birth that I had to go to direct experience, to witness a birth. I was fortunately in the Bay Area, which was the centre of the alternative birth movement at that time. There were a lot of people who wanted to share their pictures and videos. I also interviewed women. But I had to do something that's very unusual in art, which was to invent the iconography because I didn't have an image bank to draw from except for early goddess-related imagery.

MGWhen you go through [Herstory] you wonder, how on earth aren't all these works in the most important museums in the world? And the answer is because you are a woman and you're a feminist.

I find it completely mind-blowing, that me, someone who is familiar with art and was inspired to become a curator by Lucy Lippard, and knew that Robert Morris, Donald Judd, Roberts Smithson were all in Primary Structures (1966), did not know you were in it too. How is this possible? That applies also to Frida Kahlo, Mina Loy, Leonora Carrington, Sophie Taeuber-Arp—they are in the pictures next to André Breton, Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, but they're not in the record until 20 or 30 years ago.

JCThere's always this shock. That's what gets me mad. 'Oh, there were women! Oh, there's another woman!' I mean, give me a break. I do want to address this because it's not just that the patriarchal canon has erased women when history is written.

Even now, when the patriarchal paradigm and the major institutions are desperately trying to add women, non-binary people, people across the gender spectrum, artists of colour, to the edges of that paradigm, we are still dwarfed by this monumental paradigm that is construed to be art history.

What I want is institutions that are diverse, egalitarian, and representative. I want to look at Lucian Freud next to Alice Neel, and I want to make up my own mind about which one has quality. I don't want to be told what quality is. And that's how art history is taught. You are told by your professors what quality is, and that again translates into your experience of looking, and experiencing art.

MGTell me about the role of language in your own work. In the show, there is a lot of written language in the paintings. Anaïs Nin encouraged you to write. Writing and language have always been important to you.

I am curious about how language played a role both in your formation, in your life—was there a tool that you had to use again, because you had to write your own history and to write yourself, as sometimes is said?

JCI want to answer that in two parts. I first wrote because of Anaïs Nin. It was taboo, when I was coming up, for an artist to do anything in the L.A. art scene but make art. If you could write that would cast doubt on the fact that you might be a serious artist.

[Anaïs Nin] told me, 'You can't do everything, but you can write your way through everything.'

If anybody visited me in the sixties, I would never even serve them a cup of tea because that would disqualify me as 'just a woman'; the wife or groupie. So, I never thought about writing, but when the women's movement started at the end of the sixties, I was reading literature where women were talking about the experiences they were having, which was exactly like the experiences I had been having.

I left L.A. to start to try and figure out how to create a feminist art practice and to start working with young women in the hopes of helping them be able to make art where they didn't have to deny their gender like I did. We published an issue of a feminist newsletter, and I had begun to talk about what I had been experiencing in the L.A. art scene, which was singularly inhospitable to women.

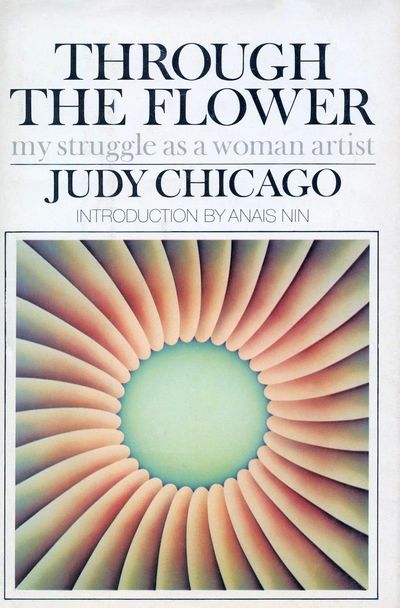

I wrote an essay called My Struggle as a Woman Artist, which Anaïs somehow read. I met her when her diaries were first being published and she was emerging from decades of invisibility. She told me I could write, but I was struggling at that point to figure out what I should do. Should I give up painting? Should I do performance? Should I do video? What would be the best way to express all this stuff that I couldn't express in the minimal framework I was trying to force everything into as a way of getting taken seriously as an artist?

She told me, 'You can't do everything, but you can write your way through everything.' Which is how I started—why I wrote my first book, to think my way through all these potential new choices. But nobody would write about my work, so I had to write about my own work. It was [like] how people talk about me being a curator. Nobody would organise shows. I didn't even know it was odd for an artist to curate her own show. I was so out of the art world, sort of marginalised.

MGYou renamed yourself and did so paradoxically in written form, the Artforum ad in which you declare you are divesting yourself from names imposed on you by male social dominance. It is a birth through language.

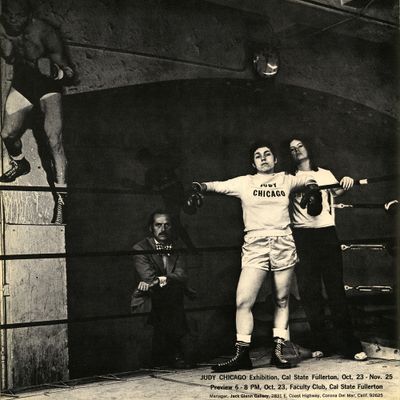

How did that come about? You associated with Ed Ruscha, and the guys from the Ferus Gallery, which I think must have been an incredible education for young artists. The Ferus guys were famous for their ads and posters in Artforum—Ed Ruscha had a photo of himself in bed with two women that said, 'Say goodbye to college days'.

JCWell, the studs were the Ferus Gallery boys, and there was Larry Bell with a big cigar, and there was Kenny Price on a surfboard, and there was Billy Al Bengston on his motorcycle. I hung out with those guys. The Artforum ad, like a lot of things, I had no intention of being controversial. I had a show of the Fresno fans and the Flesh Gardens at a gallery in Orange County, and the gallery owner wanted to do an ad. He had an idea of me in a boxing ring. I thought it was great and hilarious because it was a take-off on the boys. So, we went downtown to a gym, and I thought the guys there were going to have a heart attack when I walked in with a sweatshirt that he had had emblazoned with 'Judy Chicago', and gym shorts and big boots and boxing gloves.

My gender was hitting me in the face constantly.

A photographer who came from Oklahoma with Ed Ruscha to L.A. named Jerry McMillan took the picture. At the time Artforum was in L.A. and the editor was a guy named Phil Leider. This was the beginning of all the radical movements, many of which started in California.

He started a column, a section called Politics. And he tried to get Jack Glenn, my dealer, to run the announcement as a full-page ad and he wouldn't do it. So Leider printed it for nothing. It happened to coincide with a moment in the early seventies when a lot of women in the art world were getting fed up and were about to come out fighting.

MGWe included those two ads in a section of the show, 'Gender Games', which points to the fact that unlike some later criticism in the seventies that identify you in very arcane languages in retrospect, some of these fights seem a little ridiculous. You were criticised for being an 'essentialist' (meaning that Judy was seen as associating womanhood with biology rather than with culture, to oversimplify).

We wanted to stress how you, from the very beginning, had been aware of gender as a construction, as a pose, as a performance. In that gallery, we look at those works, those strange board games that seem to make fun of Minimalists by turning it into a dollhouse game. They are so much about strategy, about power relationships; but the power relationships are unclear because it's a chess board with no rules.

At that time, you must have been thinking a lot about gender. I'm curious, did you believe back then, and do you believe now, that art is a gender? It's a question that Lucy Lippard wrote a whole book around.

JCArt doesn't have gender, but artists do. When I was in my studio, I wasn't thinking 'I'm a woman'. I was being an artist. But as soon as I walked out my studio door, I was hit in the face with gender issues. You can't be a woman and an artist.

Of course, I understood that gender was a construct. There just wasn't that kind of theoretical language that there is now.

Even though I was in Primary Structures, I watched all my male peers on the choo-choo train. They'd be in a big show and then they'd get a gallery, then they'd sell their work and get a Guggenheim. I applied to the Guggenheim 14 times and at one point they just went 'no'.

My gender was hitting me in the face constantly. That's one of the reasons I decided at the end of my first decade of practice that I was going to deal with gender historically, philosophically, and metaphysically. I spent 15 years exploring the construct of femininity before it was called that. It used to be called 'female role'.

One day I woke up and I thought, women aren't the problem. In the early eighties, before there was queer theory, masculinity studies—before there was any of that—I started thinking about the construct of masculinity. I would go to the library and look up gender and only books about women came up because at that point, gender was considered 'to belong'. Of course, I understood that gender was a construct. There just wasn't that kind of theoretical language that there is now.

This is where having a good curator makes an enormous difference. You told me that as you were studying my career you noted that once people started organising exhibitions of my work, they were almost always from my point of view because I had recorded it in books. So, it was easy to access. But you brought an entirely different point of view to the board games and the rearrangeables through 'Gender Games'.

I knew that the rearrangeables grew out of my conditioning as a woman because I was brought up to rearrange my life to fit around men's needs. I was obviously already trying to figure it out to change the arrangement by rearranging these forms. You were the one who gave me insight into some of that work.

MGGeorgia O'Keeffe refused to be 'gendered'. She refused that reading, as you well know, because you approached her about it, right?

JCYes, when I wrote my first book, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist (1975) I reproduced work by women artists. I was living in California; O'Keeffe was in New Mexico. I wrote to O'Keeffe and asked if I could reproduce Black Iris (1926), and she said no because she didn't want to be identified with other women.

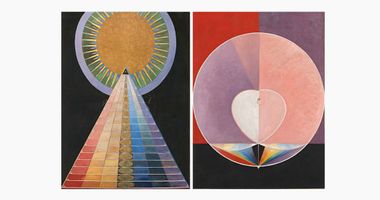

Massimiliano, you borrowed Black Iris from the [Metropolitan Museum of Art] in a kind of demonstration of what goes around comes around [laughs]. Viewing the fourth floor and seeing all that work that I've carried in my mind and in my heart, has been just completely overwhelming. I was standing with some friends in front of Agnes Pelton, Hilma af Klint, Georgia O'Keeffe, and I told this story about how she wouldn't let me reproduce Black Iris, and I'm like, 'Look at those paintings. She's a girl,' whether she wanted to be identified as such or not.

MGWith that grouping on the fourth floor and having regard to your paintings from the seventies downstairs, it is clear that there is a tradition of abstraction. You told me that for you, abstraction was a language that had to be invented by women, so they could talk about an experience that no other language would allow them to.

JCBut of course, until the Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim, there was no acknowledgement that women invented abstraction.

MGO'Keeffe was a role model to many women artists. I was looking at this book about Yayoi Kusama for a show in Hong Kong, and there are the letters that Kusama writes to O'Keeffe. It must have been amazing, and horrible, to be the only woman to whom all the other women artists wrote—asking for help, asking to become a role model for many generations of women.

Because now you are a role model yourself, does that come as a burden to you? You are an artist who is an artist, but also has the burden of representing something—I don't know if Ed Ruscha has that burden of being himself and an expression of a category. How does that feel, and how did it feel even in the seventies when you were a professor, a teacher, and a role model of some sort?

JCI have only spent six years total in institutional teaching. I've tried to teach through my art, but like my husband Donald, I am not very well attuned to institutions. I don't fit in them. I'm too much of a troublemaker. I didn't have any role models at art school. Most of the teachers were men; in art history classes most of the art was by men.

My determination of not having my work erased came from my study of women's history and discovering how many women had been erased.

I felt an absence, which is one of the reasons Anaïs was so important to me. Since I've written so many books and documented how I faced and overcame the challenges, I have to tell you, it's aggravating to me when young women ask me for a one-word or one-sentence piece of advice. I'm like, 'Do research'. I did years of research to find out how women before me overcame the obstacles they encountered.

MGSpeaking of the archive, I thought a lot that ironically—and sadly—that was also a result of marginalisation. You had the opportunity to preserve and organise your archive.

JCI cannot take a lot of credit for that. Although I was totally determined to have my work erased, when Donald and I got married 38 years ago, he was advised not to let me throw everything away by people who felt that a lot of the material—that I didn't always evaluate properly—needed to be cared for and archived.

My determination of not having my work erased came from my study of women's history and discovering how many women had been erased. Although it's not like the information's not there; it's there. It's just left out at the point at which it becomes documented history. I was determined not to let that happen to me.

And then I had an experience when I was working on The Dinner Party that made that determination even more determined, which was that I was included in a show called Creativity. It was a travelling show, and it chronicled the work of 16 creatives, and I was the only woman.

One of the young designers, Stephen Hamilton, who later ended up working on the exhibition design for The Birth Project said to me that the criteria for inclusion was that you not only had to have created something of significance, but you also had to have documented it, and they could not find a lot of women who had done that.

Now, that's a reflection of women not believing what they're doing is sufficiently important to document. I was fortunate to have people around me who felt that what I was doing and what they were doing with me was important and needed to be documented. —[O]