Patricia Piccinini

Patricia Piccinini. Photo: Phoebe Powell.

Patricia Piccinini. Photo: Phoebe Powell.

On the occasion of Patricia Piccinini's multisensory and epic retrospective, Curious Affection at Brisbane's Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA, 24 March–5 August 2018), this interview covers Piccinini's meticulous and collaborative studio practice, and the role of narrative in her work. Curated by Peter McKay, the exhibition occupies the ground floor and threshold foyer spaces of GOMA, and includes over 70 works spanning the last 20 years of the artist's practice arranged in thematic clusters.

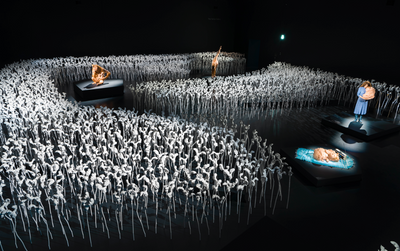

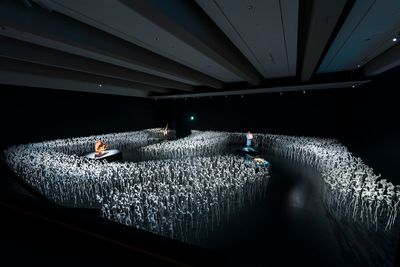

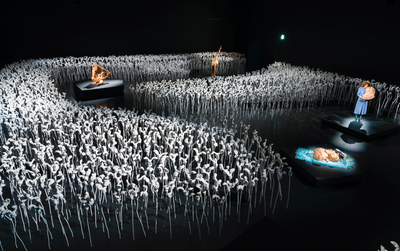

On full view is Piccinini's sculptural adeptness and tenderness of intent, with plenty of uncannily lifelike dewy-eyed chimera figures rendered from silicone, fibreglass, human hair. At GOMA, Piccinini has worked with Peter McKay to create a series of immersive landscapes that propel viewers into surreal encounters with these hybrid creatures, such as The Field (2018): an undulating field of 3,000 genetically modified flower sculptures accompanied by a soundscape. Four figures reveal themselves as viewers make their way through the setting, including The Pollinator (2017), a creature with a balletic stance and bulging orifice.

Of note is an early saturated c-photograph from a digiprint image of a woman holding a baby in a dystopic canyon landscape titled Psychotourism (1996). The image developed out of 'The Mutant Genome Project', which Piccinini created in 1995 to explore genetic engineering, consumer medicine, and the issues and implications surrounding both. The relationship between the natural and the artificial is further explored in We Are Family, the artist's presentation for the Australian pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003, and a cluster of these signature hybrid beings can be viewed in the exhibition at GOMA. Hybridity is at the core of her capacious practice; references extend from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein to the transmogrified preparatory drawings by 17th-century sculptor Charles Le Brun.

In her moving opening speech at GOMA, Piccinini spoke about the recent discovery that cellular material from the foetus is passed back to the mother during gestation. These cells end up in many places, including at times the mother's heart. Scientists think that the child's cells go to the heart to fortify it, to help it heal if needed. Fascinated with the poetic idea of reciprocal physical connection, Piccinini takes us into a magical world of wonder and tenderness particularly evident in her newest dioramas and the romantic embrace of The Couple (2018), isolated in a cocoon-like caravan.

I first met Piccinini when she was an art student at the Victorian College of the Arts in 1991, when she completed a BFA, and then we worked together at The Basement Project space in downtown Melbourne. Born in Sierra Leone and now based in Melbourne, her creative dexterity is a feature of Curious Affection. Her work moves across sculpture, video, sound and drawing, conflating nature and nurture, science and technology, in an array of works that express a sensitivity towards the mutations that have been and will become in terms of our natural development as organisms on this planet. In this conversation, we delve into the thinking behind the work.

NKYou have said that your work is akin to contemporary fables. What is the role of storytelling, myths and narrative in your work?

PPFor me, art is very much about telling stories, and in order to do that you need to have two things: something to say, and someone to say it to. That is why both narrative and audience play such a large part in my work. I think art has always been about the stories we tell ourselves in order to understand, or at least explain the world around us. That is why I am so interested in science, and also why I make connections to mythic narratives. Science is very much the narrative system that we use to explain the world, just as myth and religion were the systems that were used in the past. Both rely on trust and belief. We have to trust the narrative.

Now, I'm not saying that science and myth are the same, or that science is a myth. I think there is a big difference in the truth at the heart of these stories, and I know that science is objectively provable and that matters. However, my trust in science is still largely based on belief. I don't understand quantum physics or DNA transcription, or even really know how they work, but I believe in them. I believe the scientists as much as people once believed the priests. And, much as the stories the priests told made great subject matter for the Renaissance painters, science provides me with amazing modern myths and stories. Science gives us chimeras and transformation and cosmic forces, and it also—like religious myth—gives me a wonderful armature on which to build stories about the human condition.

NKHow is your work about a family or ecosystem of interrelated parts?

PPAt its heart, my work is about relationships. Relationships between beings, relationships within families and relationships between species, but also the boundary between the artificial and the natural. 'Family' or 'ecosystem' are both words that attempt to capture a particular relationship, and so they fit well with my practice. My work is never about one thing alone. There is always a conversation going on, even if it is just a conversation between the work and the audience.

NKThe production of your work involves tremendous labour generated from a team in your studio. What is your methodology?

PPI have an amazing studio of people who I have been working with for many years, they work with me to fabricate the pieces. Since I work in a wide variety of media, the approach varies, and we spend a lot of time workshopping better ways to do things. Overall, the process starts with drawing and then often 3D visualisation. From there we move into production which might involve manual sculpting or a hybrid 3D printing approach or a combination. The last stages of casting and finishing are always done by hand and are often the most laborious and exacting stages.

NKHow is your work about progeny and your own experience of the wonders and anxieties of motherhood?

PPI would never call my work autobiographical, in that it is never 'about' me. However, it certainly comes from me, and I can speak most authoritatively from within my own experiences. There is nothing really special about me, and my having been both a child and mother is more a source of commonality than a distinction. However, this experience as well as the very fact that I share it with so many other people, has been a huge source of fascination to me. There seems so little space in the art world for this extraordinary, yet so amazingly ordinary, aspect of life. It is rich and fascinating territory.

NKCan you discuss some of the new works in the exhibition that shift register from singular sculptures to immersive dioramas?

PPWhat I wanted to do with the new work for GOMA was create a completely immersive, narrative journey for the viewer. I always imagine my works in an expanded context, and recently I've had the chance to actually create that world around the work. The works in the final section of Curious Affection were all conceived with both the space and the journey in mind.

It has been amazing to be able to think about this from the very beginning, and to create these experiences, even these opportunities to see the gallery from different viewpoints. In the past I've only been able to create the inhabitants, but for Curious Affection I have been able to create the whole landscape—the entire world. In the past I've done all of these things in isolation, but I've never been able to put them all together before.

One of the things I like most about the new installation at GOMA is that it works on every scale. When you enter the space, you are hit by this huge vista—this sense of entering another world. The show has this macro-scale grandeur. This is not unusual in a gallery. We are quite used to this large-scale spectacle. What marks Curious Affection is that, as you look closer, the work never breaks down. There is detail there down to the eyelash scale. Unlike a film set, which only works from a distance, this space also works up close, like the real world. You see the Heartwood (2018) when you enter the space, and as you get closer to it you get more and more detail until you are standing right in front of it and you can see the pores in the skin.

NKIn 2003, you represented Australia at the 50th Venice Biennale with We Are Family. Can you reflect on this pivotal experience and your more recent accolade of presenting the highest attended contemporary exhibition of 2016, Consciousness with over 10,000 visitors per day at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil in Rio?

PPI guess every artist has these pivotal exhibition experiences, and both Venice and the CCBB were such for me, as is the exhibition at GOMA. In the case of Venice, it was this moment when I could see that my work has some currency in the wider art world. There is no denying that being based in Australia places limitations on an artist's ability to operate in the international art world, compared to being based in a similarly sized European country. However, the Venice Biennale is one of those very rare, slightly level, playing fields. It's still brutally harsh, but at least people come and have a look.

Fifteen years later I am still getting opportunities as a result of people seeing my work in Venice. The exhibition at CCBB came that way. The curator, Marcello Dantas, had seen my work in Venice in 2003 and emailed me—coincidentally, while I was visiting the Biennale in 2015—and asked me to fill in for an artist who had dropped out of their show at short notice. We were just meant to show in São Paulo, but the response was just so overwhelming that we ended up touring the show to four venues. So, it's interesting how one thing leads to another, and it sometimes takes years and years.

NKHow does Curious Affection represent the retrospective arc of your career?

PPThe exhibition quite literally spans more than 20 years of practice. The oldest work in the show is Psychotourism from 1996, and the most recent pieces were completed on site. Curator Peter McKay and I decided to structure the show in a way that was not chronological but was at least episodic, with each of the three spaces representing a different phase of my practice. The first section provides a historical perspective, showing work from 1996 to 2017 in a fairly straight museological fashion. The middle section is this very site-specific intervention into the space, and a good example of the way my practice can head off in different directions when given the opportunity. The final section is very much the present and conceived of as a unified installation of interconnected but separate works.

I think it is quite interesting for the viewer to start with an overview of the practice and a pretty complete assemblage of my main ideas, media and obsessions. This is almost like the 'theory' section, and it is light and open and clear. The last section is more like the 'practice' area, where the viewer can see how all those ideas can be put together in one narrative whole. This space is dark, unfamiliar and more complex, and perhaps more difficult, both conceptually and physically. We did a huge amount of work in that space, completely transforming it. We've added levels and new viewpoints and a completely immersive sonic element, composed by Franc Tétaz.

NKCan you elaborate on The Grotto (2018) with its sleeping, cast bats rendered in ceramic shapes and the relationship with natural ecosystems as havens of fecundity?

PPThe idea of The Grotto has been in the show from the start. It's part of seeing the show as landscape architecture, like a naturalistic garden with this series of reveals: the wide vista of the entry, with the hill in the distance, which you then climb and look out from, followed by this descent into a more compressed, claustrophobic space. Within that space I wanted to do something that was multiple but not repetitive. The objects in the Grotto are a bit obscure, somewhere between fungi, bats and fruits. They are sort of dark and glistening and a little grotesque—which is fitting for a grotto. Like many of the works in the show, they are an attempt to find a way to represent fecundity, fertility, sexuality in a way that breaks out of the usual tropes of contemporary culture. Like genetics, they derive from a fairly limited set of parts, but their combination and colour variety create complexity as a group.

NKYou have said that Charles Le Brun's 17th-century engravings and system of physiognomy are source material alongside Mary Shelley's science fiction classic Frankenstein (which is also about love). Can you elaborate on how these sources have influenced you?

PPI think both of these are a sort of science fiction—completely fantastical yet at the same time deeply rooted in the realities of the world. I love the way both of them respond to the science of their time but end up taking these ideas in their own completely unexpected direction. For me, the Le Brun images connect to this very contemporary understanding of the genetic connection between all life—the very modern idea that we have the majority of our DNA in common with bears or parrots. We are more like them than different. In the case of Shelley, I find her book an amazing discourse on care and the responsibility we have for that which we create. This is an idea I explore a lot in my work, and I think Shelley articulates it perfectly.

NKAround 2006 or 7, I visited you in New York and we went to the zoo in Central Park, where you were drawing primates. How is drawing a part of your practice?

PPAll of my work begins with drawing. Sometimes it stays drawing but even when it moves into different media, the ideas are developed through drawing. I spend days sketching these scrappy little drawings which are just for me. Often when I am drawing I will be listening to something, or exploring an idea through books or the internet, and this then feeds back into the drawings. As a work progresses these drawings will get more and more resolved or move into a completely different kind of drawing if the work itself ends up as a drawing.

NKThe peace between lightning and thunder (2018) is a diorama inspired by Queensland's Glass House Mountains, which is the culmination of Curious Affection. Can you discuss the impetus for this habitat?

PPI've always been interested in dioramas. They are these little worlds captured and represented with a combination of artifice, verisimilitude and trickery. I had my first opportunity to make one for a show I did with Juliana Engberg at TMAG in Hobart. I always loved that piece, but I've never had the chance to do another one until now. It made sense to return to the idea for GOMA.

This sequence of the show is a series of environments, starting with the very explicitly artificial space of The Field. The peace between lightning and thunder is the last thing the viewer encounters before they return to the real world, and I like the idea that it eases them back into the real world in that it essentially stands between the artificial and the natural. This has always been the space my work inhabits, although it is very much about breaking down the distinctions. The diorama is the most naturalistic looking space in the whole exhibition, yet it is entirely fake. The rocks are made of paint and paper, the trees are fake even the slate fragments that cover the ground are made of pieces of black MDF that we found in the GOMA dumpster and broke up. It's all so convincing until you get really close, and then it starts to reveal itself.

NKWhat is the role of love in your work? I am thinking in particular of the amorous embrace between the humanoids in a caravan in The Couple?

PPThe Couple (2018) is a really interesting work for me because it is the first time I've really looked at that moment—the adolescent moment, on the cusp of adulthood. I have done a lot of work about children, and parents and even older beings but this moment is something I've never really explored before. It's really pretty interesting because it is about love but not familial love, it is about a more romantic sort of love. At that moment in your life when you are between families—you are leaving your parental family but you have not yet established an independent family of your own. That is why the caravan is such a great space for it: it's a home but it is isolated and independent, with only room for two and it is on the move.—[O]