Rachel Rose on the Alchemy of Power

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Landon Nordeman.

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Landon Nordeman.

Originally trained as a painter, Rachel Rose's layered videos draw together images, sounds, and technologies to extract the affect contained within systems and structures that shape the world as it evolves.'What video offers me that painting doesn't is a way to link the technology I work with to the underlying structure,' Rose has said, 'and beneath that, to the feeling of the project'.1

First shown at The Whitney Museum of American Art (30 October 2015–7 February 2016), Everything and More(2015) is a mesh of storytelling, technical composition, and wayfinding. To create the audio that accompanies footage from a neutral buoyancy lab that trains astronauts by simulating zero gravity, Rose taught herself to use Ableton's digital spectrograph tool, creating spectrographic waves of astronaut David Wolf's voice recounting his experience of seeing earth from space with the non-verbal vocals from Aretha Franklin's 1972 performance of 'Amazing Grace' at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles.

'The remaining clips of Franklin's wordless song are further cut and mixed together,' writes Whitney curator Christopher Y. Lew, still 'fixed in its emotional register' despite its processing.2

In each composition, temporal edges expand into spaces that contemplate what was, is, and could be. Sitting Feeding Sleeping (2013), for instance, explores death through a lingering look at zoos in Washington D.C. and the Bronx, a cryogenics lab, and a robotics perception lab. In A Minute Ago (2014), Rose connects the legacy of Modernism with ecological devastation by merging a VHS clip of Philip Johnson giving a tour of his Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, with Johnson rotoscoped out and Rose's footage retracing that original interview, with clips of a hailstorm in Siberia on a summer's day.

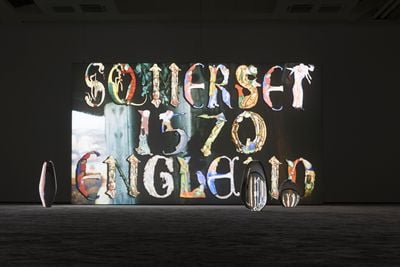

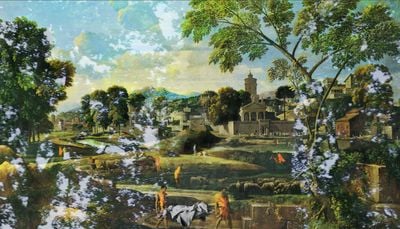

Recent projects explore the historical roots of contemporary capitalism. Enclosure, first shown at the Luma Foundation in 2019, looks at the acceleration of land privatisation in 17th-century England. The story follows a group of hustlers who use magic to acquire land cheaply from ill-informed rural inhabitants in light of the Enclosure Acts, thus turning formerly common territory—as decreed in the 1217 Charter of the Forest—into private property.

The work resonates in the present—whether the predatory nature of subprime mortgages in the early 2000s, or the utilisation of Facebook data to drive political currents. Take Recent, a member of The Famlee whose job is to learn everything about the people they seek to swindle.

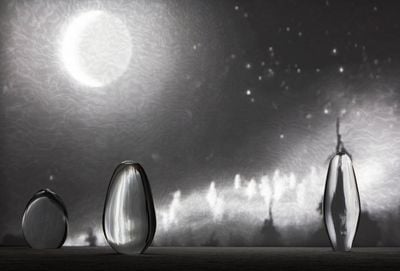

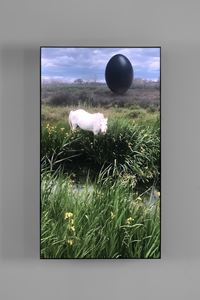

Wil-o-Wisp (2018) is also rooted in 17th-century England, focusing on the role of women and their relations to magic against the backdrop of land privatisation and the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. When the work was presented at Pilar Corrias in London (22 February–30 March 2019), egg-shaped glass objects were positioned on white carpet in front of the screen, distorting images of the film and evoking alchemical practices of the time—eggs being a recurring motif in Rose's practice. (In Enclosure, a large black egg looms in the sky, recalling the 2016 sci-fi movie Arrival.)

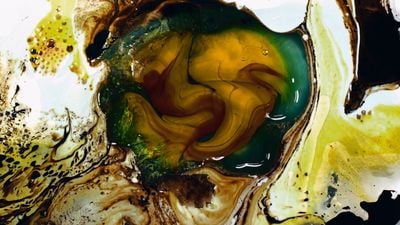

Behind the screen was a sculptural work titled The Chemical Wedding, Rock and Glass, inspired by the early 17th-century German novel Chymical Wedding by Christian Rosenkreutz, which encoded alchemical recipes into landscapes, marking a journey to a wedding.

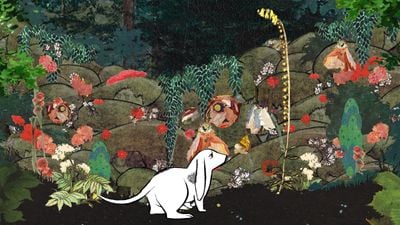

A more recent sculpture series, 'Borns' (2020), expands on this material merge, with glass-blown shapes combined with mineral rock. The sculptures were recently presented in Rose's solo exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations, the artist's first large-scale show in Paris (13 March–13 September 2020). Other works on view included Lake Valley: a cel animation following a lonely pet dog's journey from its house to the surrounding environment, with visuals harking back to children's book illustrations that evolved in the 18th century during the Industrial Revolution.

Lake Valley was also shown at Pond Society in Shanghai, the artist's first show in China (20 June–31 July 2020), where she also presented 'Borns' and 'Signs' (2020), a recent series of dream-like films comprising footage of animals in natural landscapes.

2020, in fact, was a year of notable firsts for Rose: aside from her Shanghai and Paris shows, she also staged her first large-scale show in Germany at the Fridericianum in Kassel (26 October 2019–12 January 2020).

In 2021, Rose's works will appear in group exhibitions including Sun Rise | Sun Set at the Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin (27 February–25 July 2021), as well as Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art—a touring exhibition that will travel to Toledo Museum of Art, Speed Museum of Art, and MiA Chicago between June 2021 and May 2022. In this conversation, Rose reflects on the ideas and concerns that drive her work.

SBLet's start with Enclosure, 'a heist film about survival in the 17th-century agrarian English countryside', when an acceleration of land privatisation was underway.

Within that story is the concept—and destruction—of the commons, at the time considered shared natural resources, often land, that was managed by a feudal system that allowed all members of a community a stake. Could you talk about why you chose to locate your narrative in this period?

RRI actually learned about this period somewhat randomly. I was looking at the history of narrative, which led me to Shakespeare and his innovations in story, and I read this biography about him, in which it describes his commute from London back to his country house in Stratford-upon-Avon, and witnessing all the displaced peoples along on the road from the refugee crisis that was underway throughout England at the time. I was reading about this in 2016, when the Syrian refugee crisis was happening in Europe.

During Shakespeare's time, land that had previously functioned as common—literally called the commons, in feudal land divisions—was now being deforested, chopped up, and burned, to then be privatised and sold to this new middle class of the Enlightenment: doctors, lawyers, and so on. What resulted was a mass dislocation of people and communities.

With that in mind, I decided to focus on this period for a few reasons. One, I was interested in the roots of privatisation, a kind of privatisation of space that's so central to capitalism that it's in the veins of mass global warming and environmental destruction. I had previously read Silvia Federici's Caliban and the Witch (1998) when I was working on Wil-o-Wisp, and she touches on the people who lubricated the ousting of people from their land and their communities.

In Wil-o-Wisp, I focused on the victims of this, including women, who in the film are represented by the main protagonist, Elspeth Blake—a mother and healer, who then were known as witches—but in Enclosure I was curious about the perpetrators who were pushing people out of their land.

Who were those people, these middlemen and swindlers, who worked for—or with or between—the government? This was a time when communication was slow and literacy was low, so in their roles, these men who were alchemists, disinherited sons, and wheeler-dealers, had a lot of room to manipulate within.

I was also thinking about the connection between these people and the founding of America. Who came to populate America, and what were they thinking about? One way to understand that is to look at England at that time, the major force in colonising America. Many of the people who came to America were these hustler, grifter types: people that were operating in this in-between space.

SBThese 'in-between' figures are portrayed as interlopers in Enclosure: the lords who are stealing the land, and the grifters who take their chances by scamming the system to procure land for themselves. This portrayal feels somewhat familiar, when thinking about the subprime mortgage crisis of the early 2000s in the U.S., and the idea of the marketplace as a system to be played.

RRAbsolutely. I mean, the other thing that I was interested in when researching Enclosure is how rare and new the concept of cash was then. In the film, we actually created our own cash and show cash being made.

The grifters are called 'The Famlee'—that's what they call their grifting cult—and they hustle a family that isn't familiar with cash. They may have heard of it, but they've never actually seen it. At the time, cash was a bit like Bitcoin, and everyone was making their own—it was a free-for-all, which relates to what you're alluding to with subprime mortgages. People basically didn't know what was going on.

SBAccompanying the presentation of the film in New York will be materials on the Enclosure Acts and their widespread social, economic, and ecological consequences that resonate with many of today's issues. Could you talk more about that, and the relevance of showing the work in New York, now?

RRWe've collaborated with the Yale Center for British Art, who are loaning a series of paintings and drawings that depict the agrarian British landscape during the Enclosure Movement, and these are woven into the installation.

Magic is a form of power. And that's what Enclosure gets at—that capitalism is essentially an alchemical process in which the material and the immaterial are transformed into currency.

The Enclosure Acts privatised common space—and the privatised common makes up so much of the landscape of New York today. Maybe all we have left are streets, and aspects of the parks. Other than that, it is a city made up of spaces that function as commons, but aren't.

A coffee shop, a clothing store, a mall—these are all sites of commercial consumption that mediate how we relate to one another, and remove a whole set of people who can't enter, or feel they can't. The rules of these spaces cocoon us from one another, and because a true common space is one that all people can share and that's inherently unpredictable and difficult to mediate in the most concrete way, most of the spaces in New York aren't common at all.

There's a sort of market of knowledge, which creates hierarchical points of access, and of course, when you talk about cash, it's also about creating value, which is kind of a sorcery. Magic is a form of power. And that's what Enclosure gets at—that capitalism is essentially an alchemical process in which the material and the immaterial are transformed into currency.

This was something I was interested in with Wil-o-Wisp as well. In all my work, I'm thinking about magic and the reality of magic, and I guess I was curious about this moment in which magic—or practices of alchemy, an animist relationship to the forest or to causality—is converted and translated into how we live with cash now. I don't know whether magic dies or just gets sublimated into how capitalism functions.

SBIn the film, Jacko, The Famlee ringleader, says, 'History hates the static, the strict'. Basically, he's saying that you've got to move with the times or you get left behind, which communicates that mercenary capitalist mantra to keep up in order to survive; to not stop. It sort of locks you in.

RRExactly. Enclosure came from this feeling of suffocation—from capitalism and the future of it. How do we get out of it? I don't know how we get out of it, but maybe one way is to look at one path of its origins, to at least see what life was like before and after.

All of my works are thinking about the catastrophe of capitalism and how we land in the future by looking at sites in the past that led us there.

A Minute Ago, which is about Philip Johnson's Glass House, is another version of going back to a moment in history as a way to think about where we are and where we're going. The Glass House was built in 1949. It is one of the first instantiations of glass and steel in architecture, which we take completely for granted now—everything is built in glass and steel, but we don't think about how recent that is.

Enclosure is a similar investigation, in a way. It's about this new type of built landscape, and what effects that landscape has on how we see ourselves, and how these effects relate to catastrophe.

SBLocating an origin seems to relate to the form of the egg, which is a constant motif in your work. Could you talk about that?

RRStrangely, I have eggs in almost all my works, but it has not been intentional. When I was thinking about getting pregnant, I knew nothing about ovulation, but I learned quickly and I was struck by this very basic fact that remains surreal to me—that a woman's eggs are inside her as far back as when she was an embryo inside her mother, just as her mother's eggs were inside her when she was inside of her mother.

So in a literal, material way, how do you trace the beginning of life? Do you say it's when the egg gets released and then the sperm meets it? Culturally we might agree with that, but it's so much less quantifiable. Did it actually begin when the eggs were formed in me, which began inside my mother, and then her mother?

SBHow do the 'Born' sculptures that you presented in your Lafayette Anticipations and Pond Society shows expand on this reading of the egg as this moment of instantaneous conception and ongoing evolution—a spectre that contains past, present, and future?

RRI was struck by how impossible it is to define the literal beginning of life, by this endless depth backwards, and then by how instantaneously an embryo forms, within a millisecond. The 'Born' sculptures are this very simple literalisation of that.

In the 'Borns', I was looking at a material equivalent for this thing that was happening inside my body. They are comprised of rock and glass fused together. Glass is sand, it's just pulverised rock. Rocks take thousands of years to form or more, while glass forms instantaneously. But rock and glass are this one material.

SBI'd love to delve into that more, thinking about the egg as a symbol of life's alchemical processes, whether material or biological, or virtual and technological.

RRIn Wil-o-Wisp, the egg was a creation symbol. I was thinking about the way that alchemy functioned in society then, and also about optics. I made these glass eggs that go with the film, as a way to develop how you see the film, and they were made the way that most early optical glasses were made.

All of my works are thinking about the catastrophe of capitalism and how we land in the future by looking at sites in the past that led us there.

When I was working on Wil-o-Wisp, I read this 17th-century story, the The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, which John Crowley, who wrote the introduction to the version that I read, describes as the first science fiction novel. A hero goes on a journey to this wedding, and as he goes through the landscape, everything he sees and touches and interacts with is a code for a different alchemical creation. It was like a series of equations; material alchemy spread through allegory.

SBThinking about processes of transformation in your work, could you talk about the connections you wanted to express for your survey at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris?

RRMaybe the larger framework for the layout of the show might be loosely the idea of development and magic. The show started with the 'Borns', which literally illustrate beginning—and then moved to Sitting Feeding Sleeping, which I shot in cryogenic labs, zoos, and a robotics perception lab. The work looks at how the line between death and life shifts depending on culture. This was followed by Lake Valley, which is about loneliness and how childhood has been shaped by the feeling of separation in capitalism.

SBThat makes sense when thinking about technology as a form of alchemical 'magic', which reminds me of a concept introduced by curator Yang Beichen.

Yang curated a show in 2019 with Cao Fei at Julia Stoschek that framed video artists as the 'New Metallurgists', makers who engage in an alchemical process of drawing in, filtering, and transforming matter into form that appears immaterial—a projection—but is in fact materially complex. How would you relate to this definition?

RRI think that's a perfect way to describe filmmaking and video works, because they are material, and in the case of my work, totally physical. Each work has required different degrees of production. And it can be gruelling—I've never been sorer and more exhausted than when we were filming Enclosure. Putting together a work can be literally, very physical, and in that way, alchemical.

In terms of this drawing in and filtering out of matter, that's exactly what editing is. The idea is made first in the writing and then in the edit. You need to know what story you're going to tell, and then you need to give it its voice in the edit.

SBYou said painting taught you to understand 'the gravity of the edge', but video gives you the ability to shape feeling over time. How do your video works relate to your sculptures?

RRThe sculptures I've made, like the 'Borns', are a way to think in time just as the films are, but through direct material relationships rather than narratively and imagistically.

SBCould you talk about 'Signs'—a recent series of videos that show distorted and edited footage of animals, which you showed in your Pond Society show?

RRI imagined 'Signs' as a kind of apocalyptic image between motion and stillness—what the world might look like without us, after us. They are built from photographs and short videos I take anytime I spot a white animal because seeing one always catches me off guard, like a strange omen.

SBThe animal as omen relates to how the egg appears in your work. In Lake Valley, the protagonist is a dog who moves from the confines of the house—their enclosure—to the park, which comes across as this innocent, pre-lapsarian space. While in Sitting Feeding Sleeping, technologies of cryogenics and robotics are enmeshed with the confinement of the zoo. How do these works speak to one another?

RRBoth Lake Valley and Sitting Feeding Sleeping touch on the feeling of zoos. Lake Valley is about this pet that's trapped in this suburban house, and suburbia itself is basically a zoo, a set of boundaries keeping people and certain animals inside, and wildlife outside.

In Sitting Feeding Sleeping, I was explicitly filming zoos, and I was thinking about a connection between the way that we live and the way that zoo animals live, cut off from social, reproductive, and physical cues and needs, in containers.

When you go to a zoo, it's really explicit how these conditions affect an animal's state, because you can see their depression in their bodies, slumped over like props in a theatre set, and Sitting Feeding Sleeping was a way of thinking about how that happens to us too. We now spend most of our time stuck behind various layers of glass. How does that affect our state?

SBAt the end of Lake Valley, we see the dog curled up in this square, from which a Charles and Ray Eames Powers of Ten-style zoom out happens, and the viewer takes on a bird's-eye perspective as if from space. That made me think about Everything and More and the overview effect, which describes the experience that astronauts have when looking at earth from space and seeing it as an interconnected whole—something astronaut David Wolf talks about in the film.

Is there any connection between the sense of expansion in Everything and More in terms of how you describe the zoo-like experience that Lake Valley and Sitting Feeding Sleeping both articulate?

RRThe basic premise that I was thinking about in Everything and More was how our bodies are formed through evolution to accept and reject frequencies. Right now, there are millions of frequencies around us that we're not experiencing because of the way our eyes and ears are formed and the way our brains can or can't receive things.

Learning about this astronaut's experience of being in outer space, I thought about what might happen if you extract the body from the entire evolutionary system that has formed this path for frequencies. If it's fully outside of its evolutionary conditions, is there a possibility for a different frequency absorption? And if so, what does it mean to have a body?

The only way to imagine any kind of better future in any possible way is to be open to the complexity of how we feel.

What was exciting to me about Wolf's experience of pure blackness in outer space, and then seeing the earth, and then returning from space, was his description of how his sensations opened up. He says that when you come back to earth from space, seeing something as simple as a stop sign is just unbelievable.

I thought about how those of us who have never been to space and have no ability to extract our body from its evolutionary home could seek these sense expansions. How do we defy what our body is? Drugs are obviously one way to do it, and adrenaline—there's all kinds of ways. But how do we collectively do that?

SBThis idea of defying the body—to resist the structures of definition—makes me think of Christopher Y. Lew's beautiful essay on your work. In the case of Everything and More, he talks about how your knowledge of NASA's lesser-known history in terms of its contribution to the post-reconstruction South and as a progressive force in terms of equal opportunity emerged as you were making the work.

Is this sense of emergence—of the work revealing new connections in the process of making it—common in your practice?

RRAs an artist, you wear many different hats along the process. There's the gestational research and writing period, and then you go into this production mode. In a way, you almost don't even know what you've made while you're doing it—it takes time to know what you've done.

From Palisades in Palisades to Enclosure, each of my works have been commissioned, which has meant that I had a structure through which to make them. Aside from A Minute Ago and Sitting Feeding Sleeping, which are works I could make completely by myself, it would have been impossible to make my films in the ether. I've seen each project as a complete opportunity to expand what I know, learn as hard and fast as I could, and ask questions.

In terms of production, I treat every work as school. I'm always making sure when setting up a work that there's a lot I don't know in what is required to make it, so there are always new skills I've had to acquire. When I made Sitting Feeding Sleeping, that was the first time I ever used a camera or edited or did any sound editing, so I was learning all the basics at once.

When I made A Minute Ago, I learned how to composite and rotoscope and do post-production work that I didn't know how to do before. Then when I made Lake Valley, I had to have an animatic and very clear script, because every second of animation costs money and nothing could be wasted, which then led to Wil-o-Wisp, which was the first time working with actors, and the biggest budget I had worked with. When I got to Enclosure, it was that on a different scale.

SBWil-o-Wisp and Enclosure are also ambitious in scale because they are period pieces. Is that something that you see yourself working with more going forward?

RRNo. And I will tell you why. When we made Enclosure, for example, the entire kitchen was built on a sound stage from scratch in two days, and while we got some of the costumes from the Warner Bros. archive, many costumes were made from scratch, plus all of the paraphernalia—every piece of paper you see was designed between myself and a graphic designer and then all the calligraphy was done by hand. The detail that went into making a work like Enclosure was endless.

I have so much respect for period pieces now, because I understand the amount of detail that goes in to making one. I mean, if you make a film in the present, you don't have to think about what a pen looked like in the 17th century, you can just use a pen. I think that lightness for me is quite important—especially when thinking about developing my first feature film, how to think about the production from an effectively limited and light perspective.

SBYou said that you're thinking working on a feature film. What's your vision for this?

RRI don't want to say too much about it, except that I'm thinking about the suburbs in a different era, catastrophe, and animal consciousness in the form of a love story.

There's this story I always think about, about the tsunami in Thailand in 2004 and how the elephants and other local animals ran to the mountains two days before it came. The animals had this extrasensory sensitivity—they could feel what was coming and where they were at. As a result, they could do something.

SBThis returns to the question you posed earlier about how bodies or structures might be collectively broken or defied—is this what drives you as an artist?

RRWhat drives each of my works is a deep underlying anxiety about the future and how we're going to live, where we're going to land, and not believing that how we live today is necessarily sustainable. The story we live with is definitely going to break down. Who will we be and what will we do about it?

I also think what drives my work is getting to a place in which we might not be in denial. There is this book I've been reading during this pandemic, The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker, which was written in the 1970s: it describes society as a giant machine created to deny death. The further we absorb into our denial, the harder it is for us to feel where we're at and to act. The only way to imagine any kind of better future in any possible way is to be open to the complexity of how we feel. —[O]

1 'Q/A Rachel Rose', Spike Art Magazine, 2015, https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/articles/qa-rachel-rose

2 Christopher Y. Lew, 'Room with a View', exhibition essay for Rachel Rose: Everything and More at Whitney Museum, New York, https://whitney.org/Essays/RachelRose