Song Dong

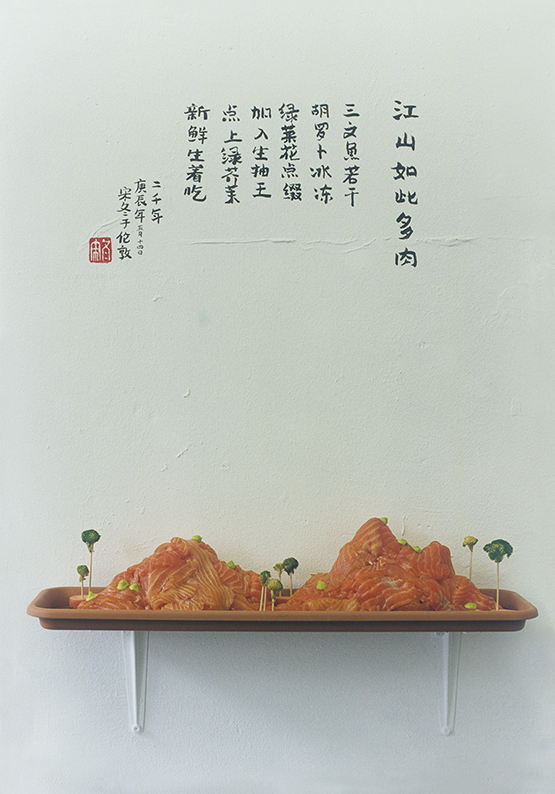

Song Dong: Sketch © Song Dong, Courtesy of Pace Hong Kong.

Song Dong: Sketch © Song Dong, Courtesy of Pace Hong Kong.

At the height of its heady sprint towards modernity in the 1990s, Beijing's urban landscape transformed rapidly, rendering it almost unrecognisable to the generation before. The horizon was crammed with cranes and skeletons of buildings, either in the process of being built, or being destroyed. To make way for a new modern landscape, each year 600 hutongs—historical dynastic era courtyard alleyways—were eradicated, displacing hundreds of thousands of residents. In the process a sense of history and community, and of traditional values was lost.

Chinese artist Song Dong was born in 1966, on the eve of Mao's Cultural Revolution and grew up in the hutongs of West Beijing. Despite the demolition and modernisation, he continues to reside in the hutongs today, drawing inspiration from them and from the generations that had lived their lives in them. Growing up he would watch his father and mother, stripped of their former life and reduced to one of poverty by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, 'making something out of nothing.' They made the most out of their meager resources from their adopted habits of thrift and frugality—toys from objects lying around the house; clothes from scraps of fabric; meals from the little food available to them.

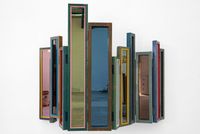

Art is life, and life is art. Song's work has always contained autobiographical elements. When his father died in 2002, his mother, crippled by grief, went about filling every inch of living space in her cramped hutong home with daily objects in order to fill the void left by her husband, embodying the maxim learnt during Mao's lean years, wu jin qi yong or 'waste not'. The displacement of the hutong residents around him, coupled with his mother's grief and emotional breakdown, provided the impetus for Song's internationally renowned Waste Not installation in 2005. Each time the work has been exhibited, 10,000 objects gathered from his mother's home have been strewn across the floor of museum and gallery spaces around the world, and have filled the wooden frame of a hutong house.

I have encountered Song's installation in various museums in the last 10 years. There was his Waste Not exhibition in 2009, in which the entire contents of his mother's tiny crammed home were organised in rows across the floor of MoMA for all to see. In 2011, I meandered around his Para-Pavilion, a warren of scavenged doors and pagodas replicating an old hutong at the Venice Biennale. Then in 2013, at the Moscow Biennale, I once again encountered his expansive blanket of salvaged old and broken items from his mother's former home. I stood before this display hypnotised and, like my Russian companion, weighed down by sadness. The work is a personal one for the artist, yet it evokes a sense of nostalgia, a longing for home and family that can be related to across cultures and borders.

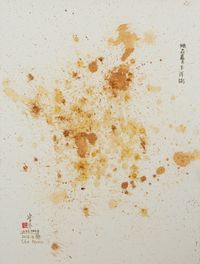

For his current Hong Kong exhibition, Song Dong: Sketch at Duddell's and Pace Hong Kong, Song uses food to explore relentless urban expansion, consumption and greed. Photographs and videos at Duddell's pay homage to Song's earlier installation, Eating the City: Edible Penjing, while guests are invited to eat cities made out of biscuits. A collection of Song's more recent pieces, including his Sauce Painting works, were exhibited at Pace gallery until recently too. In that exhibition, mandalas and other works on paper, made from condiments, cooked in sauce, and fried in pans, were presented. Inspired by iconography and ideals of Buddhism, Song uses edible ingredients as his chosen medium of art and allows his viewers to consume and contemplate his art as a spiritual process.

We talked on the eve of his exhibition at Duddell's and Pace Hong Kong about the rapid modernisation of China, his new works, and the installation that propelled him to international attention.

DDYou studied oil painting in Beijing in the mid '80s. What was it like being artist in China then compared to now?

SDFor me when I was very young, art was very important; I loved art. But during that time, only sculpture and painting was considered art. I learned oil painting at university, but I also liked to do different things. So when China opened we saw a lot more different kinds of art works which got me interested. I saw that art can use any material, and there were so many ways to do it. So I started doing installations and performance works from the early '90s, but I never stopped painting. The painting became more conceptual painting; it wasn't the traditional way of doing painting.

DDWas there a particular work or incident that prompted this shift in focus from painting to installation?

SDI think when I paint artworks; sometimes my ideas cannot really be expressed. For example, I want to write something, but in the end it's nothing. So, I use water to write diaries everyday since 1995. Also, I do a lot of things that seem to be doing a lot, but in the end it's nothing. It's like my work Breathing in Tiananmen Square; I breathe and my breath becomes ice on the ground and later disappears. Everything I'm interested in are things that are nothing. Also, eating the work, eating the landscape ... when you eat the work, it disappears and becomes nothing. What is left are the images, which are not true, they are not the real work.

Waste Not is the work that catapulted you to international attention. I have seen various incarnations of this work across the world. What was it about that work that resonated with so many people internationally?

SDI made this work more than ten times around the world. I think all people around the world have the same experience. If you live through hard times, you use the same ideas to convey them, no matter where you are. People can relate to these experiences because my work talks about the relationships of people to people. The public space connects different people. It's about the relationship with my mother, with my family, and the things I learned from them. The other relationship in my work is objects to objects. I organise the same things together. You can see very old shoes from my grandmother—her feet were bound—they were very small shoes. My mother's shoes were bigger, but very simple. My sister's shoes are simple and sometimes very cheap, other times very fashionable. But my niece (my sister's daughter), the shoes are very fashionable. This conveyed four different generations of women, so you can see the object-to-object relationship, and the development of these relationships (these women-to-women relationships), through these objects, looking for the beauty of these relationships through the objects. I think it's interesting that the history of our lives can be conveyed through objects.__

That was also a generation that experienced life very differently, one of hardships and shortages. My generation, particularly in Hong Kong, is one in which identity is defined by consumerism, by material objects and gain. It's interesting how your work with these older, more traditional values translates into contemporary society.

I think the different generations have different ideas. My mother's generation didn't really have enough money, or a lot of consumerist goods. They kept everything for the future. But for the young generation it's easier. For example, with the mobile phones, after half-a-year/a year you already change to the new latest one and you throw the old ones away. You waste a lot; everything is thrown away. So by doing this work, I learn from my mother's generation. I learnt what it is to waste and I use that in my work. But it's not really to keep these objects the way they were. I would change them. An old table would be recycled and become an artwork. That for me is very valuable, because there is then only one object like that in the world. I change the object, the shape, the concept and apply it to real life, to honour my mother's concept of 'waste not'.

DDIt seems that with your Eat the City series, you are revisiting familiar themes to Waste Not: consumption, waste, transience of life, and rapid modernisation. The city you build is being consumed and destroyed by the participants. What is the message you are trying to convey?

SDWhen China opened we saw our world change a lot. Everyday brought new change. Old buildings were taken down to make way for new ones ... and I always thought about this. I love old Beijing. I live in a hutong area. My father and mother told me we had a great and beautiful city wall, but I never saw that because the government tore it down to make the second ring road. So my idea is that maybe in the future I can rebuild the wall again. Right now I haven't that power. But I think now everyone wants to make everything new, and it has come at the great loss of many beautiful things. People have this desire for new and bigger cities. They love to have new big modern cities, yet they hate the city too. When they have a vacation they want to go to the beach or the forest to escape to nature. They don't want to stay in the city. There is an interesting paradox of living in cities.

I use biscuit to build these cities here. We use a lot of energy and time to make them. The smell and taste is really delicious, and people have the desire to have that, to consume it, to taste it. But they are made of sugar—it tastes good, but it's bad for you and can kill you. It is an illusion. It is not really food. People use desire to build up the city, but they also use desire to destroy the city.

DDIs that how Buddhism and spirituality, the concept of 'sunyata' or nothingness, feeds into your work?Right, there is no beginning and no end. Death is another life. It is a cycle. Taoism also talks about having something, but it being nothing. I'm very interested in this.

SDIn my Water Diary works (1995–present), the works look like nothing; it is minimal material. In Waste Not however, there was a lot of material. So my previous works seemingly had nothing, while this one had a lot of things, but I think a lot of things are nothing, and nothing is also a lot of things. They are the same to me.

DDHow does the venue of Duddell's—a restaurant and bar—contribute to our experience of the work, compared to a gallery? How does exhibiting these pieces inform the work and change the meaning, and the way we interact with these work? This is a space where people socialise, party and dine. It is about social stimulation rather than emotional or intellectual stimulation, as a gallery or museum space would be.

SDThis time I curated this by myself. I used two venues. Here at Duddell's, and the other space is Pace Hong Kong. Galleries are about showing art directly to the audience. It is a space for the intellect, for the mind. But this is a space for life. I think I can bring one idea across two venues and unite them. I have used blue tape to unify and connect the two venues into one idea. The physical space becomes a part of my sketch. Our life is like a sketch, that's why I titled it like this. A sketch is very interesting. It can have many changes, and also possibilities. I think our life is a sketch, a work in progress. We cannot guarantee the final outcome of our life.

DDIs food something you will continue exploring a while longer in your work?

SDI think food is the most important thing for humans. I have been focusing on it for a long time and will continue to focus on it. This time I made some cooking paintings in Pace Hong Kong. I haven't used a brush; instead I used condiments—oil, sauce, and spices. I fried paper in the pot. I use cooking material to do the work. —[O]