Slippery When Wet: Tiffany Sia's Poetry of Lived Time

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Johnny Le.

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Johnny Le.

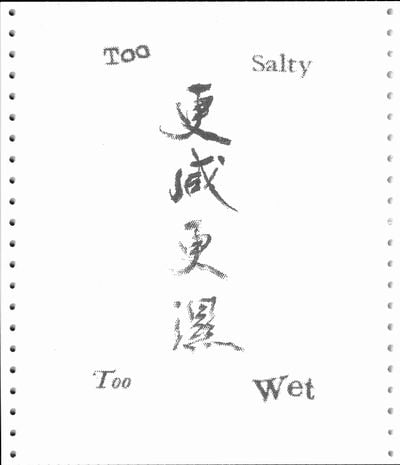

The solo exhibition Slippery When Wet at New York's Artists Space (17 February–1 May 2021), includes a virtual iteration, both for Covid-19 safety and access by a geographically dispersed community of Hong Kongers. The show's title recalls Sia's chapbook Salty Wet 咸濕 (Inpatient Press, 2019), whose pages explore Hong Kong's 'deadening' via epigrammatic statements tested on Twitter, personal online ephemera, and screenshots from critical theory PDFs.3

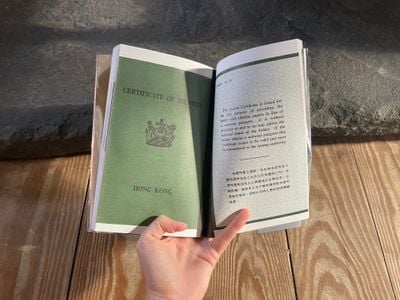

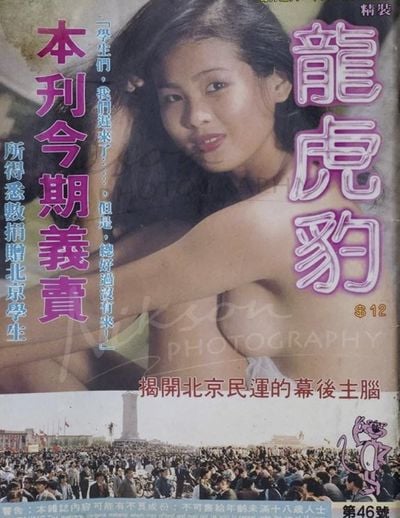

In Cantonese, 咸濕—literally translated 'salty wet'—means 'perverse'. In keeping, Salty Wet is camouflaged under the appropriated cover of a softcore magazine from 1989 Hong Kong found on the internet. The watermarked image features a coy nude alongside a photograph of pro-democracy protesters in Beijing's Tiananmen Square and a Chinese coverline that promises to 'lift the curtain' on the 1989 movement.

The critical core of Slippery When Wet is Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕 (2021), Salty Wet's sequel published by Speculative Place Press, an outgrowth of the residency Sia founded on Hong Kong's Lamma Island.

Salty Wet's aphoristic kernels about historiographical vulgarity are enfleshed in the softback book, designed with Virgil B/G Taylor, with calligraphy by Jonathan Yu, and covered in reflective mylar that is stained when touched. The line 'Hong Kong is the world's first postmodern city to die'—a counter-slogan to the city's branding as 'Asia's World City'—brings other pithy punches like 'The Pearl River Delta is the cunt of globalism.'

Sia's work is both reflexive and cutting, and Slippery When Wet is a metaphorical warp and weft between opacity and transparency.

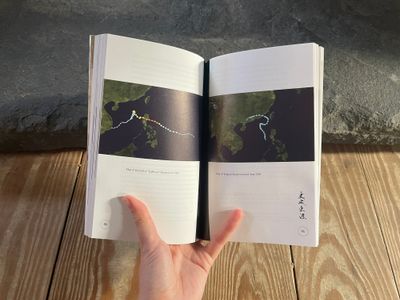

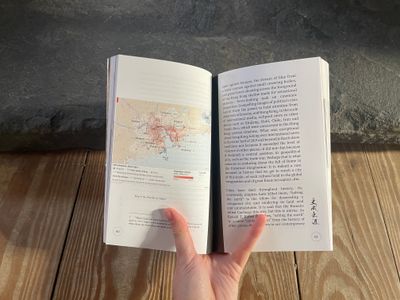

In an infrastructure map printed opposite the provocative statements, the land around Hong Kong resembles swollen labia: a foreshadowing of the artist's account of bleeding from her intrauterine device caused by police tear gas she inhaled during the 2019 Hong Kong protests. In 'ongoing recording and transmission,' Sia activates ends and frontlines in her body, 'living through timelines' in a 'doomscroll' of relentless repetition.4

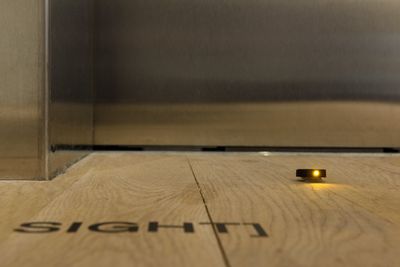

At Artists Space, a stack of Too Salty Too Wet books constituting Barriers Buy Time (2021) appropriately evokes mirror and blade. Sia's work is both reflexive and cutting, and Slippery When Wet is a metaphorical warp and weft between opacity and transparency.5 Entrance windows on Tribeca's Cortland Alley are made to appear fogged with condensation (Too Wet, 2021) while LED stage markers throughout the space make visitors aware they are being watched by surveillance cameras (In Plain Sight, 2021).

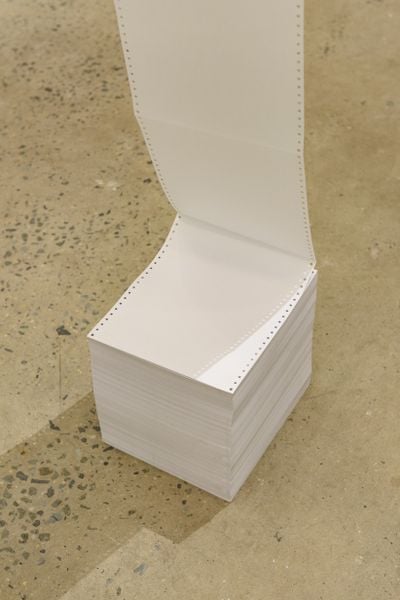

The Bastard Scroll (2021) is the full text of Too Salty Too Wet 'leaked' as a continuous form print from a dot matrix machine.6 Its emotional tumult of diaspora mourning spills over a table and chair near a corner display of seven dot matrix prints of single images otherwise hidden in the scroll's folded section: Wittgenstein's rabbit-duck illusion hangs next to Sia's delta-cunt map.

In the vestibule is another dot matrix scroll, blank and suspended (Bastard Tongue, 2021). A three-channel installation of archival weather forecasts (A Wet Finger in the Air, 2021) plays before a flickering projection of 1988 Hong Kong (Hong Kong is a Fictive Process, 2021), which vanishes for a week to make way for a live-streamed episodic landscape film (A Road Movie is Impossible in Hong Kong, 2021).

As 'subversive witness,'7 Sia is ever restless. At her 'retrospective' for the 16th edition of the Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival (BFMAF, 17 September–11 October 2020), programmer Herb Shellenberger admitted that a presentation of an artist with just one film was unusual, but Sia's expansiveness demanded it.

The BFMAF screening of her experimental film, Never Rest/Unrest (2019)—showing at Artists Space from 26 to 31 March 2021—was accompanied by Too Salty Too Wet's circulation in a 'consensual leak',8 a wordplay on vaginal discharge and unauthorised releases. The online essay 'The Leak as Discharge' (2020) followed other surreptitious disclosures: a poster-size zine for Printed Matter in New York (2020) and a performance/talk at the Lab in San Francisco (2020). Sia's art of seepage trickles to transude.

EVBCould you walk readers through Slippery When Wet, your exhibition at Artists Space? How does slipperiness continue your ruminations on the idea of haam sap, literally 'salty wet', meaning 'perverse'?

TSThere is a slipperiness in how we grasp the current moment of change for Hong Kong, and the multiple mediums in which I'm working are trying to get as close to that expression as possible. The 2019 anti-extradition protests were a time of hyper-documentation. Now that's changing.

Crisis is shifting away from the spectacle and appears photographically invisible—unseen detention centres, accounts of midnight arrests, letters from exiles abroad. We are constantly reconciling with loss. Not only the loss of a city, but also observing time itself expiring.

Siu sam dei waat ('slippery floor, be careful') is ubiquitous signage around Hong Kong—a mark of the city's climate and architecture: slipperiness is the ineffability of language, but also the ungraspability of timelines.

Slippery When Wet is made up of ten works as threads that are experienced both physically in the space, and digitally. As you approach Artists Space from Cortlandt Alley in Tribeca, you first see the windows are fogged up, as if humidity is accumulating on them, then you open the door and enter into a vestibule area where a blank scroll of dot matrix paper drops from the ceiling to the floor below. It may blow in the draft of the open door.

You walk up the stairs, and to the right is a three-channel video on stacked cube monitors. The audio switches ambiently between the first, second, and third channels, playing archival footage of weather reports from the two Hong Kong television stations, TVB and Pearl. The weather reports embody a central question in my writing: How do you see this moment on the cusp of change?

Behind the three-channel video is a lounge space where there is a projected skyline of Hong Kong that flickers. It's a photograph taken in 1988, signifying the seeable and unseeable harbingers of time and change. I.M. Pei's Bank of China building in construction in the middle of the image marks a huge change to Hong Kong's skyline: it's iconic, of course, but the design was also controversial. People were concerned about its feng shui, afraid that its angular lines were going to curse the city and sow conflict.

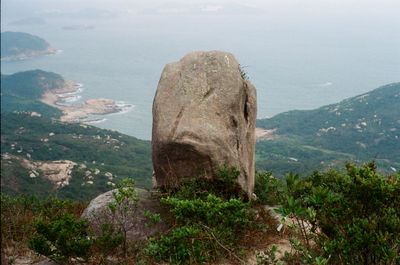

One way of defining feng shui is as occult geography. My work has to do with affect, geography, and ghosts as metaphors: I'm asking, what is this property; this architecture that observes the passing of time in shattering moments?

The show also has to hold different audiences, so the image is also about the ubiquity of seeing Hong Kong but not knowing what it is. These types of images of Hong Kong are popular in Chinese take-out restaurants in the U.S.

I actually tried to buy one such photograph from a Chinese take-out place on Nostrand Avenue in Crown Heights to incorporate in the show, but having had it for over 20 years, the restaurant and staff had become too attached to it. That very image is a sun-bleached photograph of Hong Kong that inspired the name and raison d'être of Speculative Place. Hong Kong has a massive image trail as the quintessential postmodern city.

When people think of the Hong Kong protests, the quintessential media images pop in their mind—the marches, and many of them extremely violent scenes. But in the time of living through that, there were so many moments of the banal that were most invisibly seismic.

There are designated Chinese kitchen and restaurant supplier businesses that help Chinese-American immigrants set up take-out restaurants around the country, so this image is also the banality of something so loaded, used as an ambient decorative object that provides the setting of Chinese immigrant businesses in America.

The Hong Kong skyline as a symbol generates incredible longing and ideas of consumption. So, in the show, the image functions as one of these uncanny wormholes to Hong Kong from Chinese take-out spots in the U.S. It pivots between a loaded and cutting suggestion to ambience.

EVBThere is a worm-like glitch in the centre of the projected image that resembles a meandering droplet in condensation on a window. Is that a constructed glitch?

TSYes, that constructed glitch that flickers in the moving image is inspired by an optical effect that takes place in the brain. It's called a scintillating scotoma and is something people see at the onset of a migraine. It appears in your vision; you feel like you're hallucinating, then it goes away but it's a neurological thing—your brain is doing that.

At a certain point of the exhibition, this 'wormhole' image of Hong Kong will shift into a hallucination of sorts—a live-streamed landscape film scheduled to play the week that daylight savings time switches back in the United States; when between New York and Hong Kong there will be what I call the perfect time zone antipodes: when it is 6:30 in the morning in Hong Kong, it is 6:30 at night in New York. I'll start the livestream on the minute of each sunrise, and I'll be walking throughout Lamma Island and live-streaming from vistas.

The livestream will also be viewable through the website that I worked on for the show in collaboration with the incredible web designers, Laurel Schwulst and with the help of Mark Beasley. The show is built with the digital space to create accessibility because of the pandemic, but also because it's about Hong Kong and a huge part of my community is there. Many of my works have to do with different modalities online and in reference to internet vernacular and culture. To generate discursive sites around distance, longing, and information.

Near the projection of the image of 1988 Hong Kong, which will shift into the episodic livestream, is a row of Too Salty Too Wet books, sold at Artists Space. Titled Barriers Buy Time, the books are arranged as a durational sculpture wherein, as books are sold, they disappear over time. It will look like a barrier because of the mylar covers.

I write about barriers being a way for protest frontliners to 'buy time', a kind of folk infrastructure. Producing a long text is also a way to 'buy time' because it takes a while for people to catch up to reading it. In a time of lawfare, my work is conceived as long-form fine print to be meticulously stacked and hiding in plain sight.

Then there's the central piece of the show, The Bastard Scroll, which is Too Salty Too Wet printed on continuous dot matrix paper, picking up on the idea that I wrote about in the book of history as a series of receipts. In all these forms, the show traces wetness as sites of danger, ephemerality, slipperiness, which hold potential in thinking about Hong Kong culture and placehood more broadly.

EVBSo, the title Slippery When Wet addresses both the somatic and the existential experience of the city, as well as the format of the exhibition itself. Can you discuss how it was inspired by the notion of 'exilic spectatorship' you invoke in the exhibition catalogue?

TSDesigned in collaboration with Eric Wrenn and titled TL;DR (too long; didn't read), the catalogue is the final and tenth thread of the show. It is the critical piece of text that ties all of the works I've described together.

I was inspired by Hamid Naficy's book The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (1993) about television and media as vehicles through which exilic communities construct themselves in unity in a new place. The old place recedes into the imaginary, yet at the same time, it comes into a nearness that cannot be easily grasped or surmounted in the haptics of video imagery or even magazines.

Slippery When Wet threads through the haptics of moving image and paper forms to activate the wormholes that draw the shortest distance between two places: Hong Kong and New York.

For me, it was really important to try and think about how we pass through really critical moments of history—and the ethics and trail of documentation—and how one such distance between two places and simulations of the old place can be framed as an emotionally potent and discursive site to think about placehood and timelines for communities displaced.

EVBSpeaking of critical moments of history, let's talk about Never Rest/Unrest, the film you shot on your iPhone in part during the in-between moments of volunteering on the frontlines during the 2019 Hong Kong protests.

For your conversation with Ed Halter for BFMAF, you chose to focus on two brief sequences, so I thought we could return to those images. The first sequence begins with the razor-like summit of architect César Pelli's One International Financial Centre (IFC), iconic in Hong Kong's skyline, and captured while you are taking the ferry on your daily commute to Hong Kong Island from Lamma Island.

EVBThe second sequence ends with a news report on the protests broadcast on a television inside the MTR, Hong Kong's underground. Pelli's One and Two IFC opened in 1998 and 2003 respectively, and along with the privatisation of the MTR, are representative of post-handover postmodernism and neoliberalism. You explore the lived experience of both in your work.

Could you comment on the film in relation to the controversial poetic line, 'Hong Kong is the world's first postmodern city to die,' which started as a tweet and which you then elaborated upon in both Salty Wet and Too Salty Too Wet?

TSI deliberately resist showing violent imagery in Never Rest/Unrest, and the ethics of circulating violent imagery is something I write about in Too Salty Too Wet. What can such imagery accomplish in empathy that doesn't generate a numbness in absorbing? When people think of the Hong Kong protests, the quintessential media images pop in their mind—the marches, and many of them extremely violent scenes. But in the time of living through that, there were so many moments of the banal that were most invisibly seismic.

Like, for example, the advertisements that promote Hong Kong as 'Asia's World City'. There is a sequence of the film, which is entirely shot on my iPhone, where I captured those. Seeing that ad during the time of the protest had a weird bitterness to it.

The making of the postmodern world passes through the Pearl River Delta and it is in this light that Hong Kong is not just an appendage in colonial history, but a central part of it.

In the news reports on the subway systems or even in looking over people's shoulders at their phones, I was observing the way this event and its image trail completely captured the city in so many different ways beyond just the major media outlets themselves—it was leaking and shifting our perspectives and shaping our fears.

In the film, the metaphors come up with protesters puncturing water barriers, for example, and all of the water leaking onto the sidewalk, or even the sound of protest chants echoing in a shopping mall where you can hear the largeness of the mall, where people's voices are spilling into the atrium.

The line 'Hong Kong is the first postmodern city to die' has a multivalent purpose. I am interested in the way poetic form, whether through text or film, is able to unsettle the dominant narratives of crisis. In a time of mass disinformation and intense propaganda or really heavy-handed news editorialisation, aphorisms are weaponised, so thinking through my own aphorisms was a way to swiftly unsettle and resist these structures.

When I talk about Hong Kong as the first postmodern city to die, I begin with its history as a harbour city at the centre of global trade with merchants passing through it—a port city and nexus of trade that lubricated the movement of coolies, opium, and now global luxury real estate, stocks, and more nefarious exchanges of capital common to tax havens.

I talk about my own family first touching the port of Hong Kong through the body of my great-grandfather who was captured in Fujian and trafficked as a coolie. When we think about the origin story of liberalism and colonial history, Hong Kong came about through this creation of a special economic zone created out of a colonial contract. I write about its time expiring: a contract that is always a countdown clock, first towards 1997 and the handover, then towards 2047 and the end of One Country, Two Systems. It is time expiring as a burning fuse.

Hong Kong's death was always baked into its colonial contract. When I wrote that line, tested it as a tweet before Salty Wet, it came from the dread that all this is just what the history of the city portends from its colonial foundation.

Through being the busiest port city in the 1980s and 1990s, Hong Kong—on this channel of waters and logistic flows, the Pearl River Delta—is also the material birthplace of massive material accumulation and production of the 1980s and 1990s shipped throughout the world in textiles, consumer goods, and electronics. The making of the postmodern world passes through the Pearl River Delta and it is in this light that Hong Kong is not just an appendage in colonial history, but a central part of it.

EVBThis poetic line is very different from all the media headlines that announced 'Hong Kong is dead' when Covid-19 hit and the protests stopped, and then again after the passing of the national security law in late 2020.

TSYes, to see this as the city that dies is to see the crumbling of the material birthplace of this era, of a place that has defined the consumables of our lives. To say Hong Kong is dead is not the same as the statement that was coming from people who just saw Hong Kong as a territory lost on a geopolitical map: theirs was the resignation of 'we lost this strategic hold in the Far East.' But when other Hong Kongers also used it, it was posed more as a plea, and I too invoke that urgency.

It's a plea for people to look. It's a plea for more witnesses. There is a disappearing urgency to this moment, this place, and I just want to hold on to the pieces of this timeline as it is slipping away. I think the obsession with the haptics of images, but also with text form, is my way of constantly trying to catch falling bits of these moments as they are moving across the timeline—the matter that Walter Benjamin describes as the detritus of history—and trying to grasp specifically, its mood.

The detritus of history now leaks from our digital timelines. My practice is sort of a hoarder mentality [laughs]. A friend of mine described my practice as post-Otaku—this kind of hermetic accumulation of stuff but then there is an outlet to it, hence the 'post-' prefix.

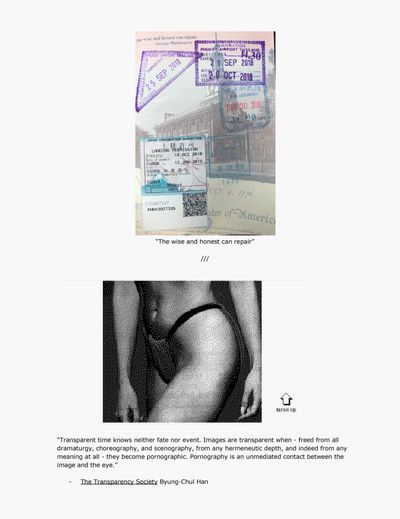

EVBWhen you presented Never Rest/Unrest at BFMAF, you and Ed Halter also discussed your subversion of the 16:9 widescreen standard with the 9:16 portrait image format on a handheld mobile device. You compared this subversion to the way you play with the covers and centrefolds of porn magazines in both Salty Wet and Too Salty Too Wet.

From Salty Wet's cover, some readers might think your interest is in the connection between politics and pornography, but it's not. Could you talk about your 'perversion' or 'corruption' of distribution systems as it relates to your resistance against the negation of lived experience in politics and media, in particular in Hong Kong?

TSThe iPhone is a more natural gaze for us at this point because we're constantly on our phones. There's a restlessness in not being able to turn off seeing metaphors for the smartphone; for example, in a doorway looking out at the sea.

Relating to the images of protest before and after it, the movement of the sea undulates with restlessness. What does the sea mean and hold for Hong Kong? The timeline is constantly leaking, full of metaphors and connections and that was the restlessness of looking at images through the phone in the in-between moments during the protests.

There always lies the potential for revelation through poetry. We rely on current and future historians not yet born to tell these times, and historians constantly look to the past, saying, 'I wonder what it was like'.

My obsessive collection of material constantly tries to get at the material of that moment, that mood, that feeling. It is constantly holding faith in that process of never resting, trying to find the material accumulation, whether immaterial by image for Never Rest/Unrest or material as in the porn magazine for the cover of Salty Wet.

Even if you consider the definition of 'subversion' to undermine the power and authority of an established institution, formally, to subvert means to take on the power of this existing structure and to flip it or torque it to deliver something else.

When I'm thinking through these mediums—whether it's the iPhone taking videos or examining how we get the news—I toggle between the dominant structure of the way we receive powerful information and attempt to tilt those structures.

Considering the mood and atmosphere of these apparatuses, a lot of my work, including what you are talking about in terms of the centrefold, is thinking through the formats of distribution systems and how they can be reframed to recover a sense of agency and to do so poetically.

EVBIndeed, you're very deliberate about creating particular conditions for reading, listening, and viewing. For example, one of Salty Wet's distribution points was the coin-operated newspaper box that Inpatient Press put in front of the Whitney Museum in New York, and Too Salty Too Wet was released alongside Never Rest/Unrest in a 'consensual leak' for BFMAF.

For artist Asad Raza's collective Home Cooking, you contributed the weekly Instagram Live performance, Hell is a Timeline (6–28 September 2020), reading aloud from texts you cite in Too Salty Too Wet. You refer to Hell is a Timeline as the 'anti-podcast, a critical theory ASMR' and encourage people to fall asleep to it.

Now, at Artists Space, you welcome the retort 'too long; didn't read'. Can you discuss the way you work through these approaches to distribution and reception in your practice?

TSI'm interested in the atmosphere of the structures I work within, whether distribution systems or mediums. Thinking about these works in their various distribution mechanisms is also so much about community. They allow me to draw the shortest distance to multiple people in different places, especially for a geographically dispersed community of Hong Kongers.

Mitch Anzuoni of Inpatient Press had the brilliant idea of doing the coin-operated newspaper box. There's a long story with that, but Salty Wet really worked within that context because of the happenstance of finding a newspaper box with what appears to be a porn magazine but is actually a challenge against dominant information delivery systems of the news, asking where the place of affect is in the news and observing that the mood of this moment, in fact, resists being named.

Thinking, also, about the idea of the 'consensual leak' of Too Salty Too Wet at BFMF, it was about my process and revealing the structure of the process while making the testing of release part of the work itself. It is important to me to invite people into that otherwise private place for an artist, especially in my thinking about internet cultures, crowdsourcing, and online communities across activism and subculture.

My obsessive collection of material constantly tries to get at the material of that moment, that mood, that feeling.

We all have at best an ambivalent relationship with platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and other apps: it's not only about privacy and security issues around data, but also about the panopticon of social and political signalling.

Instagram gave way to a whole social fabric of influencers. Unsettling that through Hell is a Timeline was this exciting dare for me. It began as a joke to read critical theory or post a bibliography on Instagram—something barely watchable. But that dare drew out a very special kind of community otherwise unable to gather beyond these digital spaces during the pandemic.

EVBIn the postscript of Too Salty Too Wet, you describe how you originally conceived it as a scroll for thread-sewn binding. Publishing it this way was not possible for a variety of reasons, so it had to be completed in perfect binding.

In your show at Artists Space, it is exhibited as an actual scroll displayed unrolled. Can you talk about the concept and structure of the scroll in your work, in particular as it relates to the livestream?

TSThe scroll unfurls as a metaphor in all of these different instances as a non-linear discursive timeline. It is a defiant and illegitimate receipt of our times, and is an open challenge against the timeline that we're constantly chasing—a counter history and a defiant retelling of what makes it into the school textbooks, but also a counter to news timeline that make up the dominant accounts of these times.

Printed on a continuous dot matrix form, The Bastard Scroll appears radically different from ancient Chinese scrolls, and many art historically significant scrolls were commissioned by emperors. The scroll Along the River During the Qingming Festival (c. 1085–1145) by Zhang Zeduan of the Song dynasty, for instance, was often commissioned by emperors for copies, and which I write about in Too Salty Too Wet.

In invoking this form, I'm also thinking about what 'scroll' means as an activity in our lives today. Scrolling on your timeline; scrolling on your phone. Then, in terms of thinking about the scroll in relation to cinema, long tracking shots are scroll-like, relating back to the ancient form, in their gaze—the way they move from scene to scene on one continuous take, and the ways filmmakers have made use of it to craft a complicated and expansive picture.

EVBIn fact, the sequences in Never Rest/Unrest are all still shots. The one 'scrolling' shot follows an escalator that reveals protest graffiti as its stairs travel up.

TSThe relationship to cinema is also explored in the dot matrix paper. It looks like celluloid; it has perforated holes to catch the sprockets of the machine on the side.

Thinking about the scroll as a multivalent and multiformed delivery system is the way I identified how I should deliver Too Salty Too Wet in its iterations. The book-length text is a bastard text of our times, because it challenges the notion of legitimate accounts in our archives, and further, is a text about Hong Kong written in English. From the thread-bound scroll, which is this place where martial arts secrets are famously printed, to this dot matrix form, and even the digital 'leaked' scroll that visitors are going to be able to scroll through on the website—all of these are delivery systems devised so that my work can be accessed and versioned, drawing the shortest distance to multiple audiences.

Too Salty Too Wet unsettles the form of a scroll, as a text about Hong Kong, a place historically withheld from being considered legitimately 'Chinese' because of its colonial history—a city that Hong Kong cultural theorist Rey Chow defiantly describes as a 'bastard child'. Hence, the title The Bastard Scroll.

EVBIn its 'scrolling', Too Salty Too Wet expands upon Salty Wet's open structure of what you call 'notes on longing and belonging' to offer 'not a love letter . . . a hellish scroll.'

Salty Wet brought together various bits and pieces from your personal archive of networked life, edited together in a way that allowed readers to participate in thinking through them. Too Salty Too Wet is, instead, tight, but strategically so. Can you talk about this shift?

TSI built Too Salty Too Wet so that it could be unravelled. But at the same time, it's true that ideally, it should be read in a linear fashion to feel like it is constantly stacking facts at you. First, you enter my body—the body on the frontlines—then all the trauma visits the body, and you're forced to sense that I'm not resting.

I only talk about sleep towards the very end. And then it veers into a dreamscape world where the voice gets tighter, technical even, and essentially LARP, as a historian, to unpack aphorisms like 'Hong Kong is the first postmodern city to die', stacking cited texts, synthesising political critique and lived experience against ongoing information warfare, and the killing of lived experience through fake news.

I resist writing too much in response to disinformation. I'm not interested in creating an obsequious text that merely exists to prove itself against disinformation, and with a similar sensibility to Never Rest/Unrest, I'm not interested in being reactionary or in parody. Instead, I'm interested in how to attempt to build new vernacular through poetic form.

So, the tightening of the text was really important to me. I call it 'unfuckability' and it is about queering historiography; it is the place for affect to exist. To create an 'unfuckable text' claims the agency to resist cooptation.

The first text, Salty Wet, is sexy. It related sexuality and desire to this libidinal political longing and it was certainly important to make that connection. But there was nothing erotic about the 2019 protests. It was traumatising and deadening. And with multiple accounts of rape in the detention centres, to pose something erotic about these times, or related to eros, seemed extremely perverse in the sense of being completely out of touch with the lived atmosphere, especially when thinking about the ubiquity and pervasiveness of tear gas as an agent that causes miscarriages. This relates back to the Pearl River Delta as the 'cunt of globalism'. This site of ongoing trauma, metaphorical and physical, is primary in writing about place.

EVBNever Rest/Unrest, which will be screened at the Artists Space exhibition, also screened with a leak of Too Salty Too Wet at BFMF and there is this very compelling relationship between the images in the film, which has diegetic voices and sounds, but no voiceover or subtitles, and the strong voice in Too Salty Too Wet, which includes some images and describes some things you saw during the 2019 protests, but mostly avoids the visual.

Never Rest/Unrest withheld subtitles and Too Salty Too Wet offers a glossary as a worksheet that the reader should complete. The combination of stubborn refusal and generous openness is a praxis that informs the ethics, politics, and even economics of your work.

TSIn writing, I am able to capture longer durations and different altitudes of time. Leaving certain scenes to text allows the protection of other individuals, making it easier to obscure their identity and for them to speak more freely. The only person I expose is myself. On the other hand, leaving expressions to film allows for something to be captured that resides outside of language that only the moving image can do.

Being on the frontlines, I asked myself what the ethics are of making art from someone else's pain. Using protest images that could expose people, where is the art in that? I think it's complicated.

I refuse the distance of the person who holds the camera. I'm both a participant and a witness—that was the case for many people who lived through the 2019 protests. What is the ethics of documentation at a time when justice is the central goal? You see a documentary, you feel invigorated by a political event, then you leave the cinema and what do you do with that?

I'm frustrated by the boundaries of the sentimental plea for witness. I want the audience to continue to question their position; I want to question my own position. Where is the place for action, as a witness or as a spectator?

The spectacle is the perversion of lived events, so I ask how I can refuse to pervert lived events in that way, subverting this perversion in order to feed into something more generative. What is the limitation of the archive towards achieving justice?

It is a challenge to swim in the unknown, not to begin with this sense that everything needs to be explained, because the act of explanation or translation ultimately conceals part of the truth. This is especially true with Cantonese, which is so fast and loose with meaning as a colloquial language.

Cantonese is effusive with meaning and guttural. I've actually had people react to my translation of haam sap ('salty wet') saying that it's a bad translation. And I love that misreading. Employing bad translation is a kind of generative refusal, and the great thing about having different titles in two different languages is the ambivalence it permits: the bastard tongue.

Refusal makes the audience work harder. Two words come to mind: community and correspondence. The hard work creates an ecosystem of people and information that gathers around the process, and it is important to me to receive all of that as an antenna for the channels of community and correspondence that other work is then generated from. To hold one audience closer, and another at a distance to challenge them.

I have a deep reverence for the piano—I haven't touched it since I was 18, but I played for 12 years. Music helps me think about structures and rhythm in my work. It's about the calibration of movements, creating dissonance, and allowing that dissonance to remain unresolved: creating a note that hangs in the air complicates the picture again.—[O]

1 Tiffany Sia, 'The Life Instinct.' Art At A Time Like This. Curated by Diya Vij. https://artatatimelikethis.com/the-life-instinct/tiffany-sia

2 Tiffany Sia, Too Salty Too Wet. Hong Kong: Speculative Place Press, 2021. p.132

3 Author's Skype conversation with Tiffany Sia. Hong Kong/New York, February 7, 2021.

4 Author's Skype conversation with Tiffany Sia. Hong Kong/New York, February 7, 2021.

5 Tiffany Sia, TL;DR. New York: Artists Space, 2021.

6 Tiffany Sia, Slippery When Wet. Artists Space, New York. February 17 to May 1, 2021. Press Release.

7 Tiffany Sia, 'The Life Instinct.' Art At A Time Like This. Curated by Dija Vij. https://artatatimelikethis.com/the-life-instinct/tiffany-sia

8 Tiffany Sia, 'Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge'. Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival. Undated. https://bfmaf.org/essay/too-salty-too-wet-更咸更濕-the-leak-as-discharge/

![Tiffany Sia, Hell is a Timeline [The Body in Crisis] (Home Cooking, 2020) (still).](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/Content/Conversations%2F2021%2FTiffany%20Sia%2FHell-is-a-Timeline-The-Body-in-Crisis_400_0.jpeg)