Artists Complicate the Mapping of an Ancient City in ‘Alexandria: Past Futures’

Hrair Sarkissian, Background (2015). C-print. Courtesy © Hrair Sarkissian.

The introduction to Alexandria: Past Futures, an ambitious arrangement of over 200 objects from and about Egypt's famed ancient port city plus 17 contemporary artworks responding to its legacy, is actually its conclusion.

Installed in the exhibition's final room is a large standing screen playing an animation by Alexandrian artist Wael Shawky: one of three works commissioned for the show, which will travel to Mucem in Marseille (8 February–5 August 2023) following its run at Bozar in Brussels (30 September 2022–8 January 2023).

Isles of the Blessed (Oops!...I forgot Europe) (2022) shows a marionette of an old lady sitting on a celestial, flame-orange rock; she recounts in Arabic the myth of Europa, the Phoenician princess abducted by Zeus.

Shawky's animation is described as the exhibition's coda: a stand-in 'for the curatorial premise of thinking [about] how the city of Alexandria'—the Hellenistic Empire's capital and Rome's second city—is central to Europe's founding myth. And it makes a clear point. Europe was named after a princess born on the Levantine shores of the Eastern Mediterranean, corresponding to modern-day Lebanon, while her brother, Cadmus, introduced the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, forming the basis of the Greek alphabet.

Evolving between the shores of its modern borders and the world to its east, then, Europe is neither a fixed space nor concept: a proposition that expands in this exhibition's mapping of Alexandria since its founding by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC.

One of the first rooms is dedicated to the Macedonian hero, with versions of his likeness opening up an expansive timeline, starting with a small bronze figure from the 3rd–2nd century BC—a miniature copy of a monumental version of Alexander riding a horse, believed to commemorate his victory over the Persians. Next to this, two paintings from 1878 depict Julius Caesar and his successor Augustus, the first Roman emperor, visiting Alexander's tomb in a performative tribute aligning both leaders with a ruler whose army and influence reached the Indus Valley.

Completing the line-up are two busts: an early 20th-century plaster cast and Gordian Knot (2013), a ceramic head by Aslı Çavuşoğlu based on a 2nd-century BC sculpture housed in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Evolving between the shores of its modern borders and the world to its East, then, Europe is neither a fixed space nor concept...

The title of Çavuşoğlu's sculpture references a prophecy that Alexander is said to have fulfilled; that whoever untied a particular oxcart in Phyriga's capital would rule Asia. But its form, per the exhibition text, is anchored to a more recent challenge: 'the long-standing antagonism between Greece and the Republic of North Macedonia', with one half of Alexander's split face shifting up like a tectonic plate.

While both countries have claimed Alexander—Skopje International airport was once named after him—it is in Northern Greece, also named Macedonia, where the ancient kingdom was located. Staking a claim to this fact, Alexander's oath at Opis, which allegedly invited 'all mortals' to 'live like one people', is inscribed on a plaque at Thessaloniki Airport.

The source of Alexander's speech—widely quoted but rarely referenced—is disputed, which highlights the constructed nature of grand historical narratives like the one Alexander embodied, whose legacy, situated between fact and fiction, has been modified to suit whoever finds it of political use.

Amplifying this template-like quality, is Iman Issa's 'Material' series (2010–2012). Six sculptures distill monuments in Cairo and Alexandria into minimalist form, like a wooden obelisk turned on its side and annotated with the wall text: 'Material for a sculpture representing a monument erected in the spirit of defiance against a larger power'.

That sense of malleability, where forms are reproduced to commemorate enduring plot-lines, finds grounding in this exhibition's first room. Installed on the main wall are three blown-up, backlit photographs from Hrair Sarkissian's 'Background' series (2012), each centring an architectural feature—a pair of classical white columns, a gold ceremonial candle stand, and a marble bridge rail—within a portrait studio in Alexandria.

These images square off with the only other work in this space: a photograph of a 2nd-century AD floor mosaic of Medusa's head housed at the Alexandria National Museum, whose mechanical reproduction extends the sense of artifice in Sarkissian's images, where representations are shown to be replicable and pliable constructs.

The dynamics of representational reconstruction expand in the room that follows Alexander's portraits, where maps of ancient and modern Alexandria dating from the 16th to the 20th centuries track the city's evolution not only in terms of design and geography, but in the imaginations of those who have studied it. Knowledge of what ancient Alexandria looked like, after all, has been mostly gleaned from written accounts and images depicted on coins, a line of which, minted during the reigns of various Roman emperors, is housed in one small vitrine.

That sense of dispersal, in which ancient Alexandria exists as fragments pieced together in a blend of fact and conjecture, forms the basis of Jasmina Metwaly's video Gorgon-avtr (2022), commissioned for the show. A medusa-like avatar dressed in steampunk red scuba-gear explores a riverside landscape before appearing in a room among ancient sculptures, their body covered in green-screen fabric as if awaiting an inevitable projection.

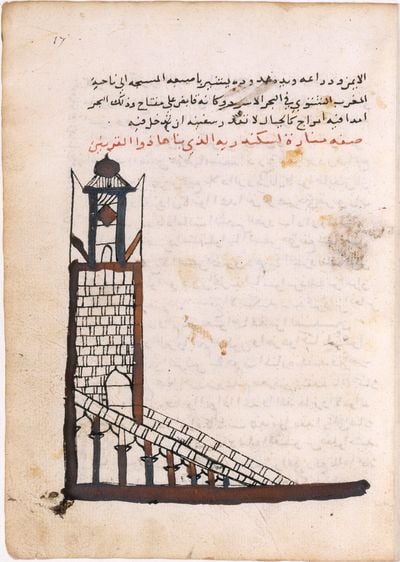

Narrating Metwaly's work is a digitally altered voice describing Alexandria through song, including the site of the city's lighthouse, among the ancient world's seven wonders, which stood where the 15th-century Ottoman-era Qaitbay Fort is now located.

As with Alexander and Alexandria, Alexandria's ancient lighthouse exists as dispersed information—something that Ellie Ga's double-slide projection It Was Restored Again (2013) foregrounds in a stream of 160 images and text excerpts from across centuries related to the construction and restoration of the building.

One image in Ga's work is drawn from an illustrated 16th-century manuscript; the original, written in Arabic, is opened to the page that appears in the slideshow in a vitrine next to the installation. It's a moment that heightens the temporal stretch created by the integration of ancient, modern, and contemporary scales in this show, with curators Edwin Nasr and Sarah Rifky weaving contemporary artworks among antiquities organised by the Royal Museum of Mariemont's Arnaud Quertinmont and Nicolas Amoroso, in order to complicate any sense of linearity.

The result is an object lesson in trans-disciplinary collaboration, where the speculative nature of art and the discipline of archaeology fuse to illuminate an expansive and nebulous field of study, given archaeology's intimate relationship with colonialism and the writing of modern history.

Take Haig Aivazian's Rome is not in Rome – Stadion (2022), a miniature amphitheatre composed like a 19th-century banquette, with an ornate wrought iron frame and studded leather upholstery. In form and title, the work emphasises how much of what we know about the ancient world was filtered through the eyes of 19th-century colonisers and capitalists with a vested interest in claiming its legacies as their own. It's a sticky, ongoing enmeshment that Alexandria: Past Futures articulates both as a project organised by a constellation of European institutions, and a study of the ancient world's methods of representational integration and instrumentalisation.

One section demonstrates the influence of Alexandria's Hellenised Egyptian culture on neighbouring civilisations, with artefacts from the Meroitic Empire (modern-day Sudan) and Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan) showing shared motifs, like the grapevine and its association with Dionysus.

In another, a terracotta lantern fragment from 30 BC–640 AD depicts the Egyptian goddess Isis nursing her son Horus as Mary is often rendered with Jesus, attesting to the spread of the Isis cult across the Hellenistic and Roman Empires and the tendency of both civilisations to merge their gods with local deities that display similar characteristics.

The result is an object lesson in trans-disciplinary collaboration, where the speculative nature of art and the discipline of archaeology fuse to illuminate an expansive and nebulous field of study...

One group of ancient figurines blending the figure of Isis with her Greek and Roman equivalents, Aphrodite and Venus, is framed by Mona Marzouk's Apparatus and Form (2022). The bright pastel-toned painting covers the walls of two galleries with monochromatic shapes articulating architectural spaces and iconographies merging symbols of fertility and ritual.

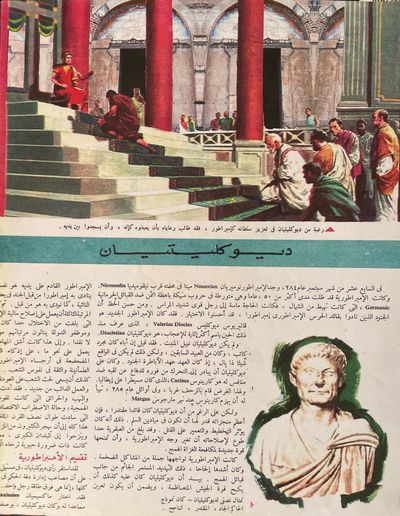

These hybrid forms attest to the fact that the Greco-Roman world, as it is often referred, was never solely Greco-Roman. It was Egyptian, Nubian, Gandharan, and more besides—a fact that highlights a curious dynamic in the treatment of ancient history in the so-called post-colonial era, as suggested by Marianne Fahmy's 2016 magazine spread, History as Proposed.

Six pages mimicking the design of the science and culture supplement Al-Ma'rifa, which was distributed by the state-published Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram in the 1970s, revolve around an abandoned rail station built near Alexandria's port by the British in the 19th century. Referencing the lack of skills transferred to Alexandrians to maintain the railway once the English departed and its subsequent ruination, Fahmy's visual narrative runs from ancient to modern Alexandria via its railway, before departing into a speculative sci-fi future of space travel.

In this imagining of what could have been had technical knowledge been transmitted to and developed by the Egyptian state, Fahmy points to an issue that Rifky and Nasr confront in this show: the false promise of infrastructure that haunts Egypt's modern history, and a spectre that resonates beyond Egypt, too.

Jumana Manna's 'Water-Arm' series (2019), for instance, is an arresting installation of limp clay pipes assembled roughshod across one gallery, which references improvisational designs created in environments with limited access to basic infrastructure, as in Palestine, as much as the kind of infrastructural decay that comes with the mis-allocation of resources in a city. In the context of Alexandria: Past Futures, the work raises a contradiction in the contemporary treatment of ancient Alexandria by the Egyptian state, especially given the way the ancient city was treated in the colonial era.

Take the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, opened in 2002 in tribute to the ancient city's famed library, which was destroyed as a result of civil war, and later cultural erasure. This mega construction, while a valuable public institution, is in many ways a symbolic project, much like the Egyptian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale: a state-sponsored exercise in bombastic archaeological propaganda in the service of nationalism and global tourism.

These hybrid forms attest to the fact that the Greco-Roman world, as it is often referred, was never solely Greco-Roman.

While understandable if you look at how antiquity was fetishised by colonial powers and appropriated to justify their conquests, such that states who suffered historical extraction cling harder to what they have in recognition of their power, the cost of symbolic historical recuperation has been infrastructural dysfunction. Not to mention social alienation, as Maha Maamoun's photographic collage Domestic Tourism I: Beach (2005) suggests, by showing Alexandria's Stanley Bridge, built in 2001 in the colonial style to beautify Stanley Bay, with Alexandrians swimming in a sea that has become increasingly closed off to them due to privatisation.

All of which connects back to Fahmy's questioning of how a place might utilise its past, and what is upheld and why—something Mahmoud Khaled's installation Painter on a Study Trip (2014) likewise confronts.

A series of framed and annotated photographs of the old Antoniadis Palace and Gardens in Alexandria, developed in the 19th century after Versailles, is preceded by a wall painting of a replica Greco-Roman sculpture from those gardens. Underneath, a golden plaque reads: 'Mural of a marble statue that a certain Alexandrian art student found difficult to draw', as if to highlight the 19th century aesthetics that persist within the Alexandrian landscape, resulting in a compromised gaze.

That compromise finds its reaction in Alexandrian filmmaker Ahmed El Ghoneimy's short film Bahari (2011), which is named after a working-class Alexandrian neighbourhood that Ghoneimy set out to film, only to be confronted by locals who spotted him videoing children playing near a fairground.

Bahari restages Ghoneimy's interrogation by two men, who press the filmmaker, played by Amr Wishahy, to explain why he is filming their community. A bewildered Wishahy eventually responds, 'I wanted to do something special', as blurry pictures of kids running happily forward, as if into the future, come into view. It's a devastating dissection of the gaze, here located in the camera of someone who is ostensibly part of the same community—Alexandria, the contemporary city—but has been identified as an outsider poised to exploit them.

That historical thickness, where past and future collapse into a grounded and complex reality, is what the contemporary artworks in Alexandria: Past Futures illuminate amid a constellation of artefacts drawn from European collections presented in a European city. With that in mind, Malak Helmy's Music for Drifting (2013), a 45-minute recording of sounds captured by a messenger bird flying along the Egyptian Western Desert and the Mediterranean Sea, operates like a compass in this show.

Documenting the sensations of a living body as it moves through space and time, from a point of origin to an intended destination, this sonic journey is perpetually anchored to the present: the very thing that holds Alexandria's many histories together. —[O]