Daido Moriyama: The Erotics of Photography

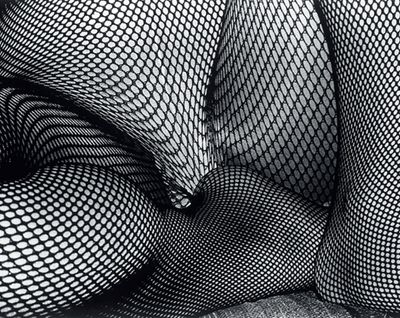

Daido Moriyama, How to Create a Beautiful Picture 6: Tights in Shimotakaido (1987/2014). Gelatin silver print. 103.7 x 153.5 x 5.3 cm. Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery.

In a documentary video published by Tate Modern to accompany its exhibition William Klein + Daido Moriyama in 2013, Daido Moriyama, one of the most influential avantgarde photographers to emerge out of postwar Japan, roams the urban streets of Shinjuku equipped with a compact digital camera.

Dressed in a low-key black jacket, his gait is relaxed but brisk. He threads through swarming crowds in commercial quarters, wanders along izakaya-packed residential areas, and strays into back alleys. Along the way, he discreetly raises his camera and clicks the shutter. 'I have always felt that the world is an erotic place. As I walk through it my senses are reaching out, and I am drawn to all sorts of things,' he says, pointing his camera at a young couple hugging at a bustling crossroad.1

Moriyama, recipient of the 2019 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography, has maintained the same mode of working since he began photographing in his twenties, crossing the city and looking for moments when its yearnings rise up to meet his.

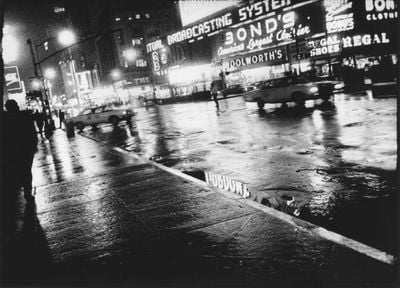

'Cities are enormous bodies of people's desires,' he has said. 'And as I search for my own desires within them, I slice into time, seeing the moment. That's the kind of camera work I like.' This on-the-prowl method crystallises in Moriyama's aesthetics: mostly monochrome, starkly contrasted, sometimes grainy to the point of illegibility or abstraction, and often charged with shoot-from-the-hip kinetics.

Born in Osaka in 1938, Moriyama abandoned a design course at Osaka Municipal High School of Industrial Arts in 1958 to become a freelance graphic designer before shifting to photography. In 1961, he moved to Tokyo to join the groundbreaking photography collective VIVO, assisting one of its founding members, Eikoh Hosoe.

VIVO's experiments were the culmination of a large midcentury amateur photography culture fuelled by the country's production of film and camera equipment after World War II—a style that countered 'informative' mainstream photography in Japan at the time.

'From the outset', notes Tate curator Simon Baker, 'Moriyama was less interested in following any specific photographic tradition than he was in developing a new means of daily praxis—to make the everyday simultaneously subject and process.'2

Moriyama has amalgamated several influences, including avantgarde writers Jack Kerouac and James Baldwin, repurposing the titles of their best-known works, On the Road and Another Country for his own photo-essays. In terms of a working method, Moriyama has affinities with American photographer William Klein.

Between 1956 and 1960, Klein published a series of photography books on the street life of four international capitals, starting with the seminal Life is Good & Good For You in New York (1956), followed by Rome (1959), Moscow (1960), and Tokyo (1960). The latter came as a revelation to Moriyama. 'I was so touched and provoked by Klein's photo book, that I spent all my time on the streets of Shinjuku, mixing myself in with the noise and the crowds, doing nothing except clicking, with abandon, the shutter of the camera,' he said.3

The primary photographic question that occupies Moriyama is one that belongs to the realm of erotics, rather that of ethics or politics. This erotics is to be differentiated than eroticis despite his occasional engagement with the latter. While photographers such as VIVO's Nobuyoshi Araki see the world through an almost exclusively sexualised lens, Moriyama's view apprehends and expresses reality through visceral processes.

In the early books that Moriyama published, from Japan: A Photo Theater (1968) to Another Country in New York (1971), he shows himself to be a seasoned peripatetic, his thinking honed by the short-lived but influential left-wing photography magazine Provoke, which ran three issues in the late 1960s. As its subtitle 'provocative documents for the sake of thought' suggests, the magazine refused forms of documentary in favour of the are, bure, boke style—wild, blurry, and out of focus. It could be said that, Moriyama has never strayed from this style.

Moriyama's 1972 landmark publication, Shashin yo Sayonara (Farewell Photography) takes the Provoke injunction to 'leave the world of certainty behind' to its extreme. At the time he shot this series, he felt as if 'the world was fragmenting' and was constantly troubled by questions around the purpose of photography.4

He recalls picking up the negatives thrown out by his friends in the darkroom and realising that these were 'also images of the world'—a thought that allowed him to understand that 'anything was possible.' With photographic possibilities radically expanded, Farewell Photography is difficult, at times nihilistic. Some images look plainly 'bad': one photo in particular looks burnt, an aesthetic failure as well as a technological one.

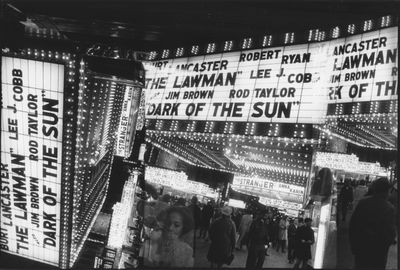

While Farewell can be seen as an attempt to strip photography of its style, Another Country in New York (1974), published after his sojourn to the city in 1971 with Yokoo Tadanori, reflects on the medium through a classic modernist move of self-reflexivity—to insist on the 'photographed-ness' of photography.

Each image in the photo-book contains two vertical cells of sequential films, a format that allows for photographic self-reflection. Scenes in quick sequence show the camera's movement in time; some images are stacked and folded, with skyscrapers toppled over billboards and pedestrians over monuments, to show the camera's rotation in space. Some shots are repeated to show photography's inherent seriality.

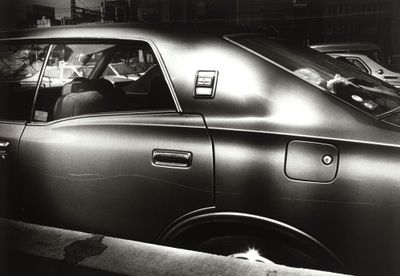

Moriyama's work of the 1980s, bookended by Light and Shadow (1981) and Lettre à St. Loup (1990), continues the practice of photographic self-awareness, but through renewed formalist interest.

While light and shadow were used to liquidate Moriyama's visions to impressionistic imagery in his early years, the 1980s saw the fundamental building blocks of the photographic language gaining aesthetic ground in Moriyama's work. From the matte underside of a car's tyre and the translucence of an empty bottle to the lyrically dense patterning of libidinous fishnet stockings, the play of light is tightly orchestrated to endow mundane corners and abject subjects a sense of grace and often monumentality.

The decades that followed marked an era of increasing traction in the West for the artist, who has had major solo exhibitions at places like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Daido Moriyama: Hunter, 1999–2000) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog, 1999–2001). This is also an era that saw both explorations in new filmic frontiers—including polaroid and the digital camera—and constant renewals to past productions, including Light & Shadow, which was revised from its 1981 version in 2001, and Farewell Photography, revised in 2006 from its 1972 version.

Moriyama often speaks of his photo-books as open-ended sites where readers can enter and exit at whichever page and in whichever order—an expanding of his oeuvre that accommodates the reader's own wandering.

The dreamlike flow of 'ambiguity', which Moriyama identifies as paramount to any good photography, still permeates his work and indeed continues to energise the artist. In the Tate documentary, Moriyama, in his seventies, remarks with hopeful buoyancy: 'I could never see the city with an old man's eyes, or as if I understood everything.' —[O]

1 Daido Moriyama at Tate Modern, 2012, Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/55201008.

2 Simon Baker, 'Daido Moriyama: In Light and Shadow', Daido Moriyama, (Tate Publishing: London 2012).

3 Graziano Scaldaferri, 'Discover the Captivating Work of Acclaimed Japanese Photographer, Daido Moriyama', The Culture Trip, 2017, https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/daido-moriyama-the-father-of-street-photography-in-japan/.

4 Daido Moriyama at Tate Modern, 2012, Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/55201008.