Danielle Dean: From Fordlândia to Amazon Inc.

With a practice that looks into the impact of advertising on the body and mind, British-American artist Danielle Dean—whose works span video, painting, and installation—is not unfamiliar with the media's tactics of persuasion.

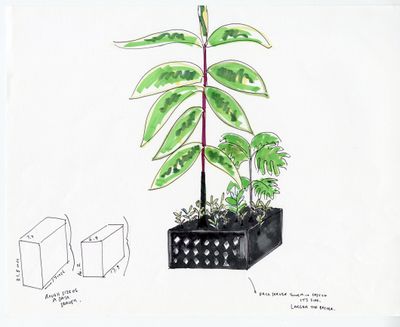

Danielle Dean, Preparatory drawings for Amazon (Proxy) (2021). Courtesy the artist.

The artist's 2018 video work Bazar, for instance, explored the enmeshed semiotics of consumerism and culture through the catalogues of Bazar de l'Hôtel de Ville, a department store founded in Paris in 1856, with invited performers engaging with cut-out pictures and actual products.

But while recognised for the subversive nature of her works, what first appears to be a critique delivered through the language of mass communication in fact sets aside moralising rhetoric to raise pertinent associations that only ask that viewers take notice.

Dean puts these tactics to use in the five-channel video installation Amazon (2021), on view as part of the artist's Art Now presentation at Tate Britain (5 February–8 May 2022) in London, which foregrounds Dean's research into the physical costs of capital aggregation, which reduces bodies to variables in the production chain.

Amazon started as an inquiry into the language of car advertising and its environmental repercussions, prompted by Dean's research into Ford Motors' archives in Detroit, during which she discovered the history of Fordlândia, Henry Ford's 1928 labour settlement in the Brazilian rainforest.

Conceived as an industrial utopia, Fordlândia was modelled after the Midwestern farm towns of Ford's childhood, not only inheriting their American-style housing, but nine-to-five schedules, puritan values, and hamburger meals at the detriment of local customs.

Despite allegedly providing health care and decent pay, Ford's imposed cultural assimilation on Brazilian workers—football and tobacco became contraband items around the plantation—led to a 1930 revolt and the settlement was abandoned shortly after.

Echoing the earlier performance Amazon (Proxy) (2021) shown at the Performa 2021, Dean's video work Amazon draws loose connections between Ford's experimental city and the present, with a focus on Amazon's online platform Mechanical Turk (AMT). Since 2005, AMT has provided remote human labour tasked with sorting and generating data for enterprises like Google and the U.S. Army Research Lab.

Comparing the assembly chains pioneered by Ford at the turn of the 20th century to the gig economy today, Amazon considers how capitalistic structures are maintained through specific forms of labour organisation. In both, alienation from the physical output of the work revokes agency and compels adherence.

Across the five screens that compose Amazon, four self-identifying AMT workers narrate and deliver lines penned in collaboration with Dean, who, wearing dark shades and brandishing a cane, takes on the role of the billion-dollar conglomerate at the head of such enterprises.

To evoke the isolation of remote work and the alienation of AMT workers, who are kept in the dark about their employers and actively discouraged to communicate with each other, the five-channel installation is composed of four small displays in front of a larger screen at the back.

Amazon is notable not for its conceptual engagement but for its desire to connect viewers with workers who are otherwise confined to their own isolations.

One by one, screens light up to show footage of AMT workers—in bed, at their desks, in the living room with laptops open—carrying on with their morning routines, as if filmed moments preceding a remote meeting. Each worker shares their reasons for staying with Amazon Inc., some more enthusiastic than others. Equally pertinent motivations find expression in simple contentions to support a family, or to avoid face-to-face interactions.

Articulating discarded histories, a female voiceover speaks about the process of colonisation prompted by monetary incentive in Fordlândia, before Amazon's footage reels back to the present.

In one segment, contractors speak about not being paid if they become ill. In another, we learn compensation for their labour can take the shape of Amazon coupons and canned peaches. 'I use mine to buy cat litter,' one worker confesses.

Punctuating the frame-to-frame transition are images of a neon junglescape collaged from old Ford advertisements, recalling the artifice of the American Dream, which grounds promises of freedom in individual conquest and the overpowering of nature.

The same narratives are championed by American film studio Walt Disney Pictures, which has long propagated ideals of man vanquishing land—and followed with its own attempt, Disneyland—that have imprinted on generations. Dean recovers its bold cursive font, noting that Walt Disney and Ford had been close friends.

Around the screens, a display of potted artificial plants, in the same fluorescent shades as the junglescape, are scattered on the ground—the bright foliage eventually makes its way from the backdrop image into the workers' homes, referencing the physical invasiveness of Amazon Inc. In one scene, a worker rests in bed, thermometer in mouth, in a room where lime green leaves spiral down wooden furniture.

Delivering a monologue on non-existent rights, a female android A.I. assistant wearing a pink blazer that matches the junglescape appears from time to time to answer to Dean's instructions. In a flat robotic tone, she agrees to carry out their plans to suppress rebellion.

There is a temptation to read the contents of Dean's installation at Tate Britain as pure critique. But in Dean's representational universe, entertainment can often overshadow otherwise serious political concerns, in which ideas are eclipsed by neon jungle scenes just as they are raised, retaining the only constant of visually gratifying frames.

Still, Amazon is notable not for its conceptual engagement but for its desire to connect viewers with workers who are otherwise confined to their own isolation. —[O]