Hito Steyerl: How To Build a Sustainable Art World

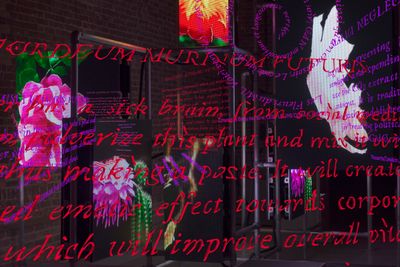

Hito Steyerl. Courtesy Andrew Kreps Gallery. Photo: Trevor Paglen.

Hito Steyerl. Courtesy Andrew Kreps Gallery. Photo: Trevor Paglen.

'A Picture of War is Not War', we read in Hito Steyerl's iconic film November (2004), an essayistic Super 8 film tackling the definition of terrorism constructed around the figure of the artist's best friend Andrea Wolf, who was killed as a terrorist in 1998 in Eastern Anatolia after she joined the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party).

Mixing documentary and fiction with scenes from a feminist martial arts film that the friends made when they were teenagers, this study on the mechanism of representation—on images and their circulation and exploitation—became a point of reference for a generation of artists who reconstruct history using archival and personal material at a time when the old feminist motto 'the personal is political' has acquired new dimensions.

Using in-depth research and at times humour, Steyerl questions the politics of images through her essays and artworks, which have recently experimented with artificial reality and app technology.

This is The Future (2019) and Leonardo's Submarine (2019) at the 58th Venice Biennale (11 May–24 November 2019) used A.I. technologies to create imaginative future scenarios that reference the military-industrial complex and the large corporations involved in computer technology, pointing to the unpredictable ways that artificial intelligence can affect the future.

Steyerl's installation Power Plants at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London (11 April–6 May 2019) explores ecological and political power using a collectively produced digital tool that shares data on social housing, wealth distribution, and workers' rights within the communities of Kensington and Chelsea around Hyde Park, where the gallery is located. Created in cooperation with local researchers, community groups, and unions, the Actual RealityOS app is free to download and uncovers the working conditions surrounding one of London's main tourist attractions.

Institutional critique is a focal point in Steyerl's work. Her June 2009 essay for e-flux Journal #07, 'Is a Museum a Factory?' touches on the art world's role in the canonisation of hyper-production, while the video lecture and lecture-performance Is the Museum a Battlefield? (2013) maps the links between the arms industry, military conflicts, and the art world by tracing the manufacturers of the bullet that killed Andrea Wolf, leading to the conclusion that nearly every big western company involved with military organisations is potentially an art sponsor of museums and institutions.

Rather than withdraw from the art system in response to this complicity, Steyerl has endeavoured to show this work in as many institutions as she can, trying to reverse the direction of the bullet that killed her friend and many others.

Engaging the institution as a means to subvert it is a logic that feeds into more recent projects like Drill, her recent show at the Park Avenue Armory in New York (20 June–21 July 2019), where she brought forward histories connecting the building hosting the exhibition with the founding of the National Rifle Association.

During her opening speech for her exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, Steyerl addressed the institution's relation to the billionaire art philanthropist Sackler family, whose role in the opioid crisis has provoked a chain of reactions, including the Louvre's decision to remove Sackler's name from one of its wings, and the Serpentine announcing it would forgo future Sackler funding.

In this conversation, Steyerl considers new definitions of the global and local, and reflects on the effectiveness of institutional critique in relation to the art institution as a site for corporate 'artwashing', discussing how art workers today might respond to such toxicity.

DZIn your text for e-flux Journal #98, 'Remembering Okwui Enwezor', you say that Enwezor's 'idea of an (art) world is under attack, if not breaking apart altogether'. Could you elaborate?

HSWe are living in an age of oligokleptocracy, in which the power of wealth is aggressively supported by right-wing governments and many populist movements. In the art world, this leads to both a predominance of an increasingly monopolised market and increasing parochialism. A sense of international perspective gets lost, which is a wider sign of rampant isolationism.

Social media is boosting the toxic bubble that many local or national art scenes are going through. The breakdown of any progressive prospect for digital technology hasn't helped either, nor has the transformation of a lot of art criticism into call-out clickbait. An idea of progressive internationalism, as Okwui proposed, is progressively abandoned or gets snowed under constant waves of affect and outrage manipulated by monopolist platforms, and solidarity is swapped for identity.

The idea of the global was already massively undermined in the era of neoliberal globalisation, when it became some kind of Potemkin-style cover-up of criminal privatisation in many parts of the world. It is not a surprise that the art world is now faced with a violent—and to some degree necessary—correction towards the local.

This situation could provide a chance to reconstruct internationalism minus oligarchic globalism in the art world, allowing progressives a chance to push discussion about contemporary vernaculars. However, I am afraid that this scenario may still be some time away, mainly because a sizable part of the left has entered a phase in which outrage replaces organisation. Now, the kleptocratic modes of government installed by the West post-89 in so-called Eastern transition countries and way beyond have returned to their sources.

DZEnwezor's era was one of broadening the borders of the mainstream art map. How would you define the notion of the centre today?

HSThere is no centre—just aggressively contracting fortresses of local canons, and less connections in-between. Some aspects of it also make sense: the art world has been relying for too long on cheap airfares and fossil-based tourism and transportation. The challenge now is to maintain communication in a sustainable way, beyond monopolist communication platforms. The artist residency economy needs to be reimagined too, with its paradigm of enforced nomadism.

DZYour film November is a reference point for artists who reconstruct history through a mix of archival and personal images in order to reflect on the ways in which the past feeds into the present. How do you see such a 'mission' today, given the ubiquity of images and the advances in the technologies to both produce and disseminate them?

HSNo image is innocent; every single one can be weaponised. This is what November talked about and has intensified. On the other hand, there is a new onslaught of history-making happening right now, so perhaps it's more a time to engage with the present.

DZHow has your focus on the status of the 'poor image' evolved? What are the challenges faced by an artist dealing with a world of floating signifiers in today's technologically advanced capitalism?

HSThe relationship has become even more asymmetrical and hard to predict. I mean, compare the culture industry that Adorno and Horkheimer dealt with, with that which involved Facebook, Amazon, and the corporate art world. In this environment, a poor image is actually an unseen, unpopular, 'unliked' image that disappears into the surplus matter of imagery that no one cares about or even actively cancels.

DZIn your exhibition Power Plants at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, you address what you call 'the elephant in the room'—the art world's complicity with the Sackler family. You compare the institution's connection to the Sacklers as being married to a serial killer and wanting a divorce. But is it really so easy to get this divorce? And why exhibit in a gallery featuring this name at all?

HSI am not a divorce lawyer and I didn't consent to getting married in the first place, so in a way, it's up to the institutions to figure out how to get divorced, especially because only they know what kind of contracts they signed. But after Nan Goldin and P.A.I.N. [Prescription Addiction Intervention Now] protested at the Louvre, it happened very quickly—mentions of its Sackler wing were quietly removed from its website and signs hastily taped over. The president explained that the naming contract ran out years ago, but it seems P.A.I.N. had to call this to his attention.

Why not assume there are more institutions that have 'forgotten' to remove names, which are no longer supposed to be there in the first place? In general, even venerable public institutions like the Louvre are vulnerable, because of the growing—and in the Anglo-Saxon world, often desperate—dependency of art institutions on private funding.

The underlying question is: why should any cultural space be named after donors in the first place? Why not after artists, scholars, or other important contributors to the field? Why should art spaces be transformed into monuments for corporations? A public space like the Louvre, with its long history as a public museum linked to the revolution and the foundation of the republic, has an important public legacy to protect. Why should any such space be symbolically turned over to the oligokleptocracy? There was a literal battle to win these spaces for the republic, and it seems the Louvre is aware of that legacy and is reconsidering its public appearance.

It's not the artists or the public that should move over and leave these spaces. Who is more important to the Royal Shakespeare Company: Mark Rylance or BP? Should the Louvre have been left to the royal family? Having said that, a tactical retreat or withdrawal may sometimes be necessary. It is important to build alternatives, and a parallel infrastructure that sustains itself outside this mess. But even if the fight for public cultural space were a rearguard struggle, it would still be worth fighting. If some art workers can completely unlink from current economies, in most cases it means they can afford to because they have other resources. So, I really don't think that throwing in the towel and just fleeing downhill is going to help anyone but oligarch stakeholders.

DZCan institutional critique still be effective today, when institutions absorb and defuse radical art tactics? What new forms can critique take?

HSI have always advocated doing things, including art, outside of efficiency evaluations. I find the view that every struggle today is absorbed or rather embraced to death is a tired truism that belongs to the bygone phase of neoliberal globalisation, when things were still somewhat predictable. Now they actually aren't. Look at the Kanders case at the Whitney Museum in New York. I don't think at all that the institution absorbed the protest going on outside and inside the museum. Activists, artists, and art workers both in and outside the biennial managed to create a dynamic that could no longer be contained by anyone and that no one predicted. If they had just relied on the cynical certainty that nothing will ever change, it would have been a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Having said that, I don't think that personalising campaigns is a good idea as it detracts from the structural issues. However as no one knows what—if anything—is going to produce any effect, people have to test all options with no guarantees. It's the most rational thing to do. Even making mistakes usually means gaining experience. That's the hopeful part of all the new movements around museum politics: ideally, people practise how to organise and act in common. No one can take that experience away ever again. In the long run, this will be even more important than whatever the stated short-term goals are now. This is also why it's important to try to define broader concerns within campaigns, because the process itself can quickly become toxic and unsustainable, especially when driven by social media algorithms and clickbait.

I am sure Nan Goldin's aim was not primarily to warn off continental art institutions to reconsider their drift towards donor dependency. Yet, this is what is happening already. Ultimately, it will be important to move beyond protests against individuals and try to frame the problems more generally in terms of a new charter for the art world: a set of principles that include different aspects, like pay, sponsorship, governance, transparency standards, representation, sustainability, and so on, like a new deal for museums. The fact is, though, that the art world will fragment even more around this into some oligarch decoration and speculation sectors and more interdisciplinary not-for-profit ones; the reality is also that longer structural changes will be delayed the more the art world fractures.

DZWhat are the key challenges when it comes to producing a more sustainable art world in terms of its working conditions?

HSArt practices becoming economically sustainable beyond the existing art world is really a major challenge. Completely unlinking from existing systems is only possible for those who have the material means to do it. This is one more reason to keep the contestation going within the existing art world while trying to slowly build other forums. This is an optimistic view, because there might not be enough time to get anywhere before reactionary forces gain the upper hand. The more pessimistic or realistic option is some kind of exodus, basically a brain drain from the art world, precisely because it has become unsustainable—way too unequal and too toxic overall. This is what will happen if the art world does not change: it will cease to be an option for younger generations, a bit like Facebook. It has started already.

DZYou are also a professor at the Berlin University of the Arts. How do you see the current interrelation between the cultural industry and the academy?

HSIn general, academia is much less important to the art world intellectually than it was during Okwui's time. It is more important in terms of it having become a corporate and financialised degree or debt machine, exploiting art workers of different kinds and establishing boring and very homogenising templates of professionalism.

DZYour recent works explore artificial intelligence and its implications for society. Which do you find more crucial in this process, A.I. or society?

HSGood question, I bet this is what many strategy divisions at platforms concern themselves with in order to automate the latter by using the former. In terms of art, there are interesting developments happening, including the alignment of artists with big V.R. platforms, data, or P.R. corporations—a bit like emulating the Formula 1 system, just now it's about tech artists being supported with a lot of corporate money and knowhow. Let's see how long nonaligned artists will manage to subsist in this sector. A similar imbalance has existed for a long time in terms of the art market—artists with vast resources have been judged on the same terms as those that do not. Now the same is repeating on the level of tech support, which ultimately is part of a cold war about future tech standards and platforms. It's a bit like doping in sports.

At a time when the art world has significant overlaps with defence—and cyber defence—corporations, art institutions could undergo a similar internal process and ask themselves: what else could we do with our vast knowhow, organisational skills, and resources?

DZYour work has also reflected on nature and the ecological crisis, tying into a wave of (techno)paganism in the art world. What do you think are the stakes in revisiting nature through art today?

HSNature has been partly constructed by humans, as some argue quite dramatically since colonial times, but definitely also before. Large parts of it are social and technological artefacts, not least climate change. The paganism you mention is part of a disenchantment with technology and automated bureaucracy. It can point to an extremely reactionary direction, as any German could tell you. It can also point to earlier times in human history, when massive technological and social transformations were underway like in the Renaissance.

At these points in time, magic and science formed different tangles, magic perhaps being a foreshadowing of sciences to come, or an effort to assume some irrational or informal kind of agency. From a more speculative perspective, I think that parts of the art world today belong to another emerging magic or scientific tangle. For me, the Venice Biennale is sort of like what Stonehenge might have been—a cult centre to playtest emerging forms of oppression, excess, and hierarchy; a cult of the accursed share. In Stonehenge you might find pig bones—in Venice you will find plastic sticks to impale olives for spritzes. This kind of applied ritual is more important than the superficial pagan gloss that artworks might display. It's the infrastructure itself that is partly occult.

DZCould you tell us about any future projects you are working on?

HSI am working on a script on a variation of the Lucas Plan for the art world. The Lucas Plan was created by arms workers who were threatened by redundancy in the seventies. They came up with a catalogue of socially useful products they could make with the knowledge and resources they had instead of creating weapons. At a time when the art world has significant overlaps with defence—and cyber defence—corporations, art institutions could undergo a similar internal process and ask themselves: what else could we do with our vast knowhow, organisational skills, and resources? Most people working in and with art institutions do not want to decorate or reputation-launder defence, pharmaceutical, or fossil energy industries. So, how to recuperate the energies wasted on these activities and deploy them differently? —[O]